The Brexit Party leader is launching an anti-lockdown movement – but can it succeed?

Nigel Farage is no stranger to forming political parties around a central policy. For much of his early years as leader of UKIP its key focus was immigration (tied in with Euroscepticism), while the Party stood for what it said on the tin.

With a withdrawal agreement passed and the transition period set to end in weeks, Farage has turned his sights to a new issue – lockdown. Last week he announced that he intends to rebrand the Brexit Party as Reform UK, aiming to challenge the Government’s approach to tackling the coronavirus – which he described as “woeful” – and the lockdown measures in place.

But is there much appetite for such a party? Currently, the data suggests there isn’t.

Public views on COVID-19 restrictions

The public currently take a dim view of the Government’s handling of COVID-19, with our latest data showing that 62% think they’re doing a bad job at handling the crisis compared to 32% who say they’re doing well. However, many of those who disapprove of the handling, do so for opposing reasons to Nigel Farage. A third (35%) of the public think the current lockdown measures in England do not go far enough, compared to just one in six (16%) who say they go too far.

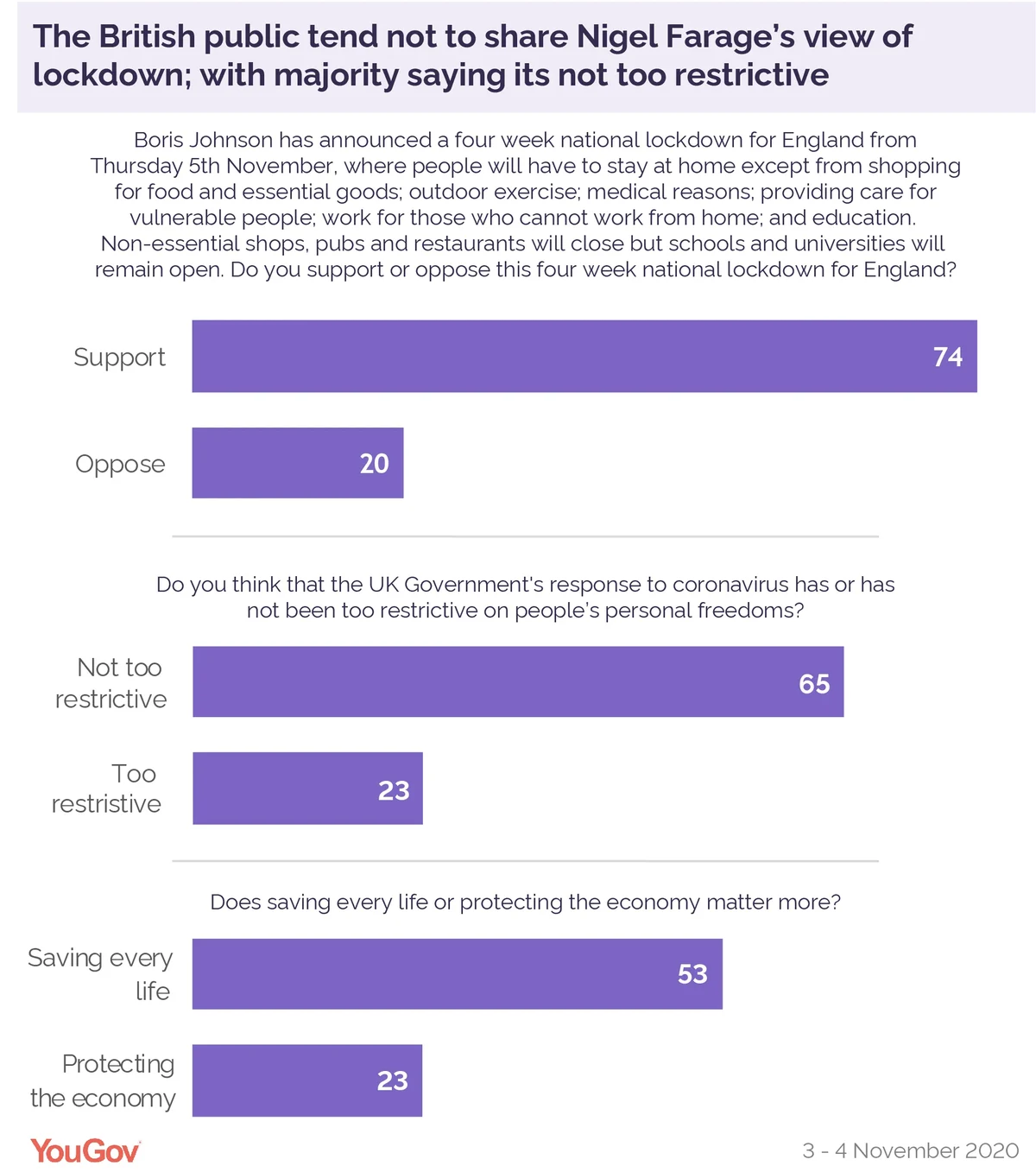

Farage stated that the new national lockdown would “result in more life-years lost than it hopes to save”. However, here the vast majority of the public again take the opposite view to him. By 74% to 20% they support the measures that have been brought into place. This has been the case throughout the crisis, with the public reliably supporting any measures the Government implements.

Another concern of Farage’s is that through another national lockdown, “Businesses and jobs are being destroyed". YouGov’s data consistently finds that the public pick healthcare over the economy when prioritising the two conflicting issues. Our latest figures show that 53% state that trying to save every life matters more than protecting the economy (23%).

In September, Nigel Farage said that the “restrictions are a threat to freedom”, but here the public tend not to share this view. Nearing two thirds (65%) think the Government’s current response is not too restrictive on personal freedoms compared to just under a quarter (23%) who think it is.

Could the party succeed?

So while it seems there wouldn’t currently be broad appetite for an anti-lockdown party, this doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be a success. In all of the questions discussed above – national lockdown support, focus on economy and restriction on freedom – around a fifth of the public hold positions in agreement with Nigel Farage. If all of these people rallied around his rebranded party, it would amount to a sizeable level of support. However, this is much more easily said than done.

With immigration and Brexit, Farage had much more of a buffer to play with. In the year leading up to UKIP’s win in the 2014 European Parliament election, between 48% and 60% of the public picked immigration as one of their top issues facing the country. This was also coupled with the overwhelming majority of the public consistently saying that the levels of immigration into Britain were too high.

With Brexit, the starting point was 52%. In the 2019 European Parliament election, the Brexit Party – protesting Theresa May’s Brexit deal – delivered Farage’s most successful win to date. They were backed by a combination of the 23% who supported a no-deal Brexit at the time and many of the 13% who supported an alternative to May’s deal.

Do Farage supporters and lockdown opposers overlap?

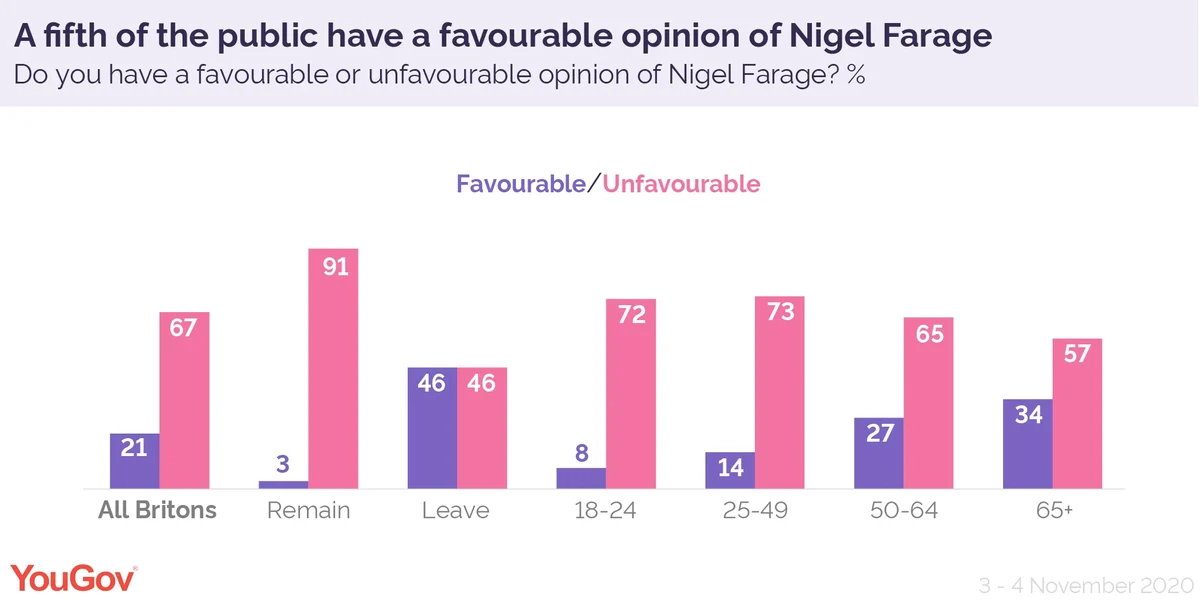

One thing Farage can use to his advantage in building support for his party is his personal brand. As with opposition to lockdown, a fifth (21%) of the population currently have a favourable opinion of him. The key question, though, is whether Farage supporters and lockdown opposers overlap.

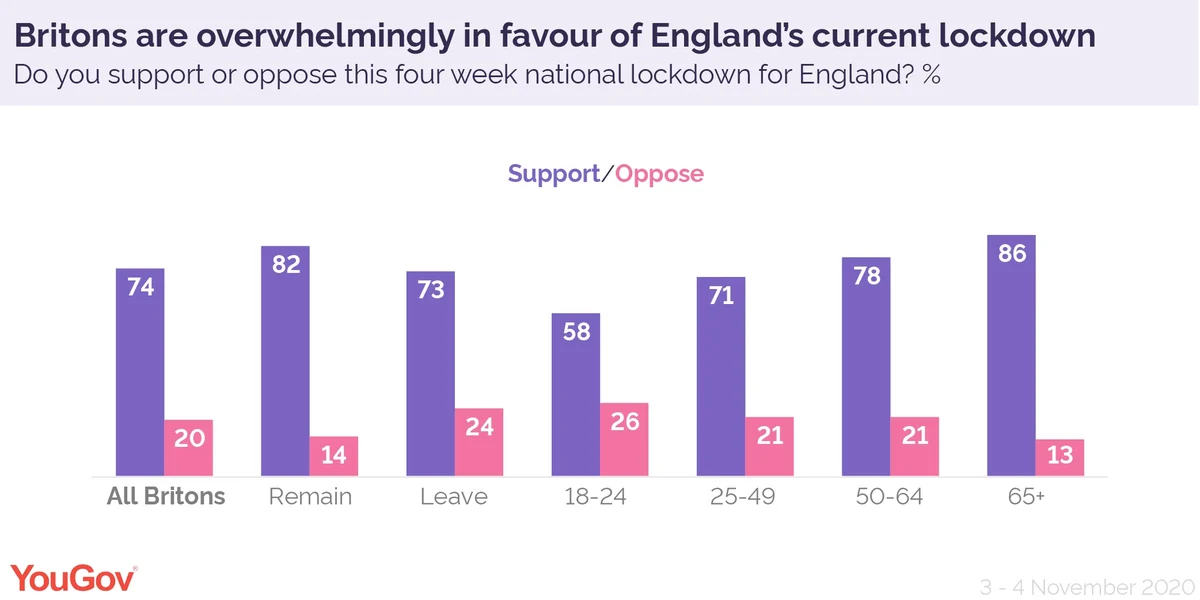

Age is a big dividing line here. Nigel Farage is much more popular with the over-65s (34% favourable) than under-25s (8%). However, older people are the most supportive of the recent lockdown (86%) and young people the least supportive (58%).

Naturally, Leave voters are a key group who support Farage (46% hold a favourable view of him) and while this group are less supportive than Remainers of lockdown restrictions, they do still support the new measures by 73% to 24%.

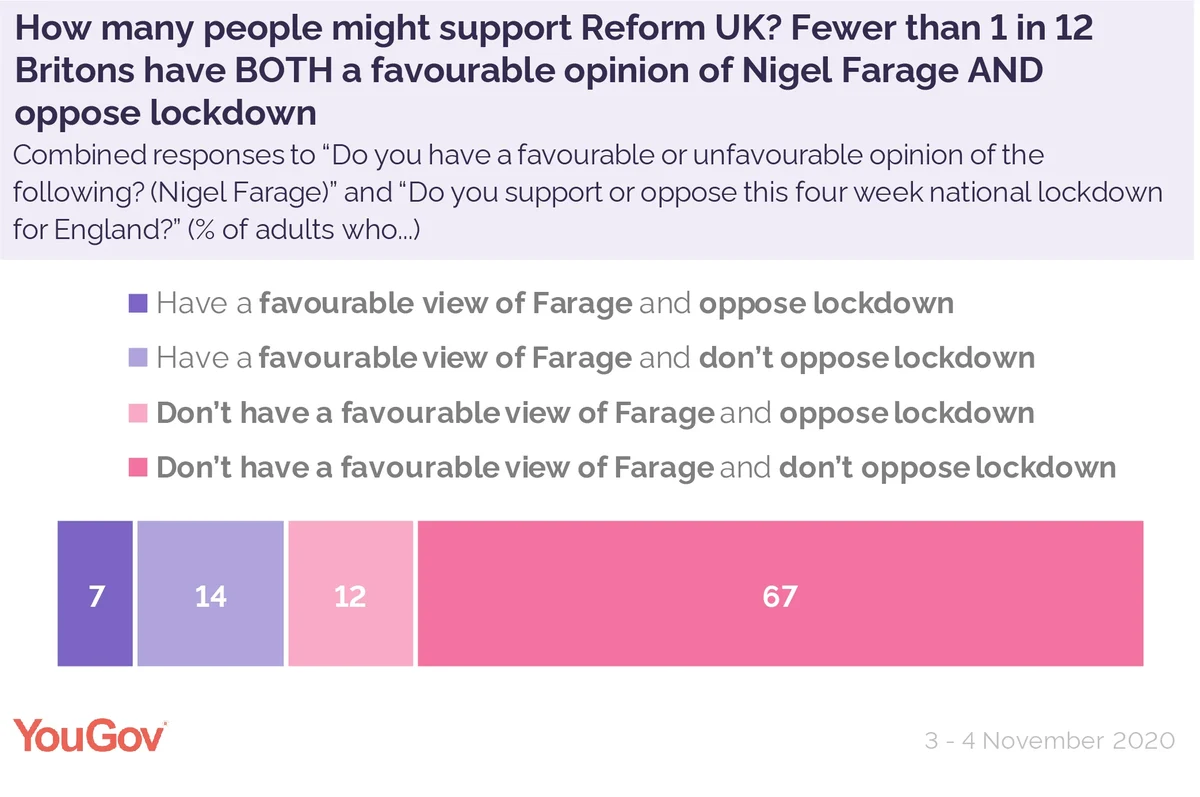

To really dig into likely support for Reform UK, we can cross support for lockdown with approval of Farage and create four distinct groups:

- Those who have a favourable view of Farage and oppose lockdown (7%)

- Those who don’t have a favourable view of Farage and oppose lockdown (12%)

- Those who have a favourable view of Farage and don’t oppose lockdown (14%)

- Those who don’t have a favourable view of Farage and don’t oppose lockdown (67%)

By this logic, Reform UK’s core support is around 7% and two-thirds (67%) of the public currently don’t satisfy either of the two criteria tested. To build on the 7% he would therefore either need to convince his personal supporters of the pitfalls of lockdown or convince lockdown sceptics that he is the man to fight for them in this battle.

However, the data suggests that both of these groups might be hard to chip away at. Of those who hold a favourable view of Nigel Farage but are not opposed to lockdown, half (50%) support the measures “strongly”. Among those who are anti-lockdown but not fans of Farage, 57% have a “very” unfavourable view of him.

Of course, perceptions change and while this most recent national lockdown has strong support, it has fallen compared to the 93% who supported the first lockdown back in March. If this trend continues with any potential future lockdown measures, then the anti-lockdown pool available to Farage will widen.

Additionally, his own ratings have fluctuated and are far from their peak. Just after the European Parliament elections in 2019, Farage’s personal approval was at 30% and there is no reason they won’t increase again if he is able to get enough airtime. The key to success though, wouldn’t just be growing these two groups separately, but growing the number of people who fall into both.