The election campaign is beginning to resemble the trenches of the First World War: full of mud and noise, but neither side breaking out.

Last week’s big push by the Tories – to frighten voters with the prospect of a Miliband government beholden to the SNP – has failed to puncture Labour’s defences.

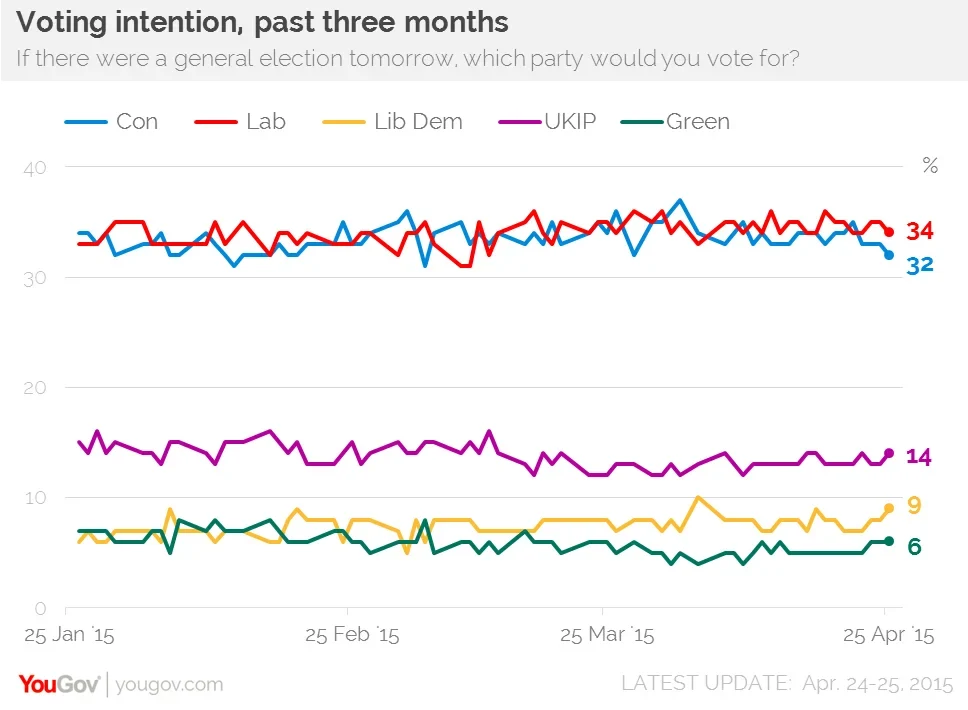

Indeed, little has changed since the start of the year. Small surges of support have never lasted. The Conservatives have so far failed to exploit their two big advantages: the electorate’s preference for David Cameron as Prime Minister, and the Tories’ continuing lead on economic competence. If anything, the Conservatives are slipping backwards: at 32% their support is their lowest for four weeks.

They should not be surprised. Just 14 per cent of the public think the Tories have run the best campaign in the current election, a little behind Labour, on 17%, and way behind the Scottish National Party on 26%. The Conservatives have failed even to enthuse their own supporters; just 39% of them reckon their own party’s campaign is best.

It’s a measure of the Tories’ failure to maximise their vote that when we ask people who they would support if Boris Johnson led his party, he converts a two-point deficit into a three-point lead.

An insight into the Conservatives’ performance is provided by the results of a tracking question that YouGov has posed every day since Easter. We ask people whether they have noticed anything positive or negative about Labour or the Conservatives. People who reply “yes” to any of these questions are invited to tell us, in their own words, what it was.

Two big lessons emerge. The first is that every day, far more people tick the “negative” than the “positive “ box for the Tories, whereas Labour’s figures are generally in balance. Scaling up our findings to the electorate as a whole, 6-7 million people each day generally commend the Conservatives for something positive, while 11-12 million notice something negative.

For Labour, the daily average has been around 8 million both positive and negative.

Secondly, Labour’s top issue, health, has consistently generated far more spontaneous positive mentions than the Conservatives’ top issue on the economy. Since last weekend, average of 2.5 million people a day has credited Labour with saying something positive about health, while the Tory average for the economy is just half that: 1.2 million.

Our findings also suggest that this week Conservatives have backfired in their charge that a Labour would rely on the SNP. At the peak of the row, on Tuesday and Wednesday, almost three million people cited this as a reason to feel negative about Labour – but it made far more, almost five million, feel more negative about the Tories. By yesterday [Friday], both figure were down, but the Tory negative mentions, 3.3m, still massively outnumbered the 1.4m who gave it as a reason to think negatively about Labour.

All that said, Labour has been unable to take a decisive lead by fighting on the NHS, living standards and the Tories’ persistent image as a party for the rich.

YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times helps to explain why both parties are at the low end of their recent levels of support. Neither Cameron nor Ed Miliband is regarded as particularly honest, even by their own supporters. When voters are presented with a list of adjectives, both positive and negative, their responses tell a clear story. Cameron, Miliband and Nick Clegg all share the same top attribute: “uninspiring”, followed closely by “negative” (Cameron) and “dull” (Miliband and Clegg).

Only Nicola Sturgeon breaks this bleak pattern. By a big margin, Britain’s voters reckon that, above all else, she is “passionate”.

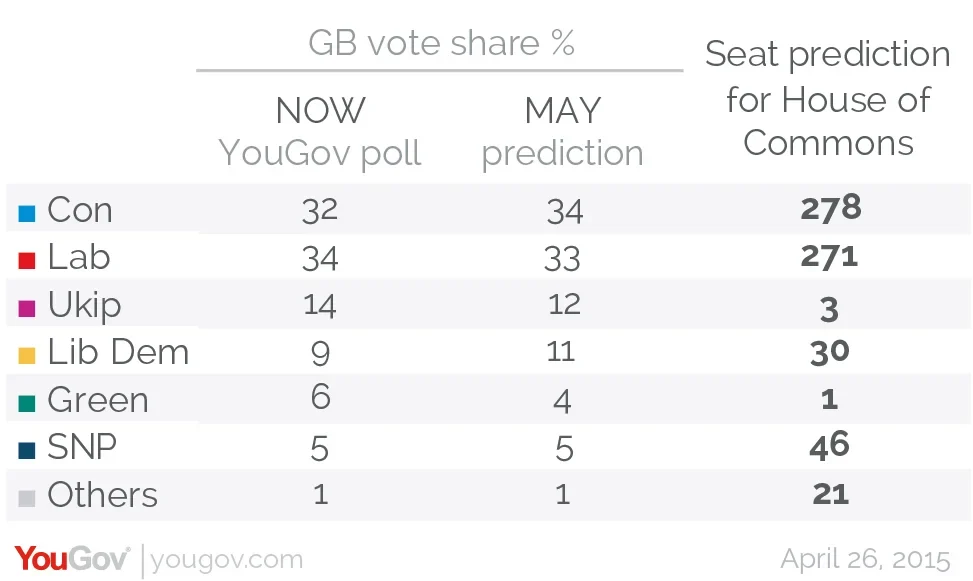

With relative strengths of Labour and Conservative little changed since Easter, this week’s forecast is little changed. I still expect a small late shift to the Conservatives and the two main parties ending up neck-and-neck in seats. If, by some miracle, my figures were exactly right, then Miliband would probably end up as Prime Minister, despite leading a slightly smaller contingent of MPs than Cameron.

This is because Cameron would not have enough MPs to win a vote on the Queen’s Speech. The total number of left-of-centre MPs would be 324 (Labour 271, SNP 46, Plaid Cymru 3, Green 1, Northern Ireland’s SDLP 3), while Cameron would reach only 321, even if he could persuade both Ukip and the Lib Dems to support him.

There are two reasons why things could change between now and May 7. The first is that last-minute shifts have happened fairly often – in 1970, 1974, 1992 and 2010.

The second is contained within YouGov’s latest results. We are able to track the views of many of our panel members through time. And while the overall figures have changed only slightly since Easter, this is not because everyone has made up their minds but because the shifts below the surface are cancelling each other out.

In the past fortnight, around three million voters have switched from one party to another, while a further three million moving to or from the ranks of the don’t knows. The task for the parties in the final ten days is not so much to shatter fixed loyalties as to win over a decent share of the many voters with shallow preferences.

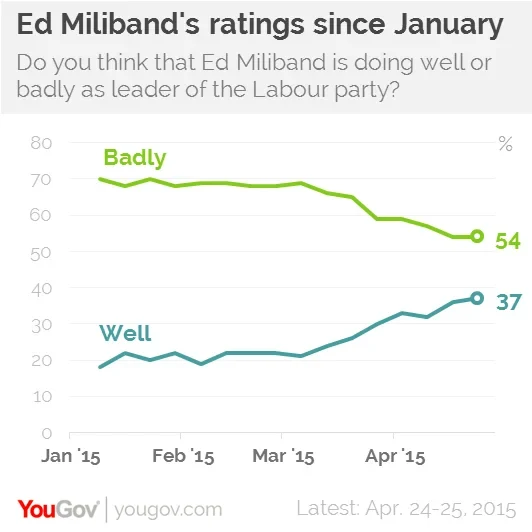

For Labour, this means reviving the momentum of Miliband’s personal ratings. Up to last weekend they had been climbing steadily, but this week there has been little further change.

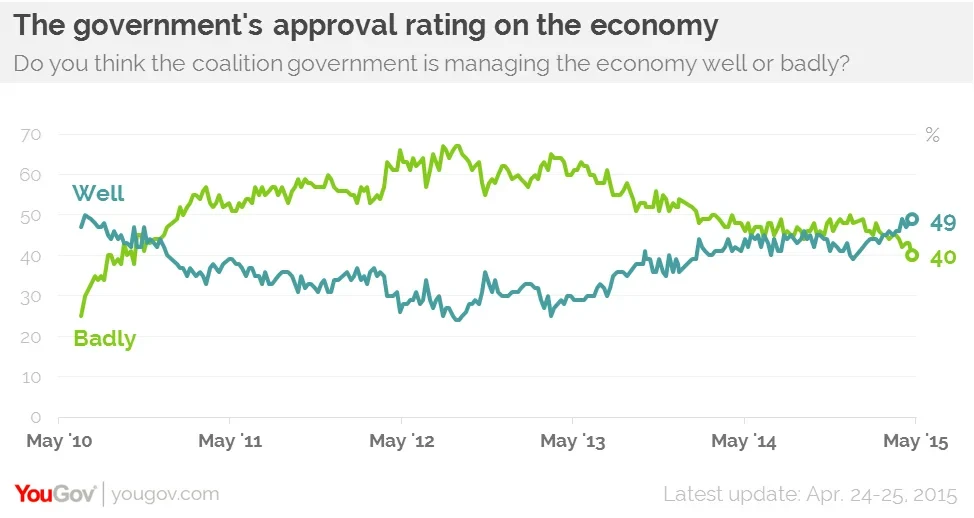

For the Conservatives, it means reviving Plan A – talk about the economy and little else. Their recent forays into inheritance tax, right-to-buy and the influence of the SNP have won them few votes. But our latest survey contains a finding that could prove crucial.

Back in August 2012, just 24% said the coalition was managing the economy well, while 67% said badly. In the past two years the figures have steadily improved. By the start of this year, 42% said “well” while 49% said “badly”. This weekend, the government’s figures are its best since the coalition’s early honeymoon days: well 49%, badly 40%.

The Tories should be able to convert this into extra votes in the days that remain. But to do so, they must improve greatly on a campaign that, so far, has left most voters distinctly unimpressed.

This blog is an edited version of commentaries over the weekend in The Times and Sunday Times