Despite having popular policies, new YouGov research shows that the Labour leader still has to convince centre ground voters he would make a competent Prime Minister

Jeremy Corbyn noted in his Conference speech this week that “it is often said that elections can only be won from the centre ground. And in a way that’s not wrong - so long as it’s clear that the political centre of gravity isn’t fixed or unmovable, nor is it where the establishment pundits like to think it is.”

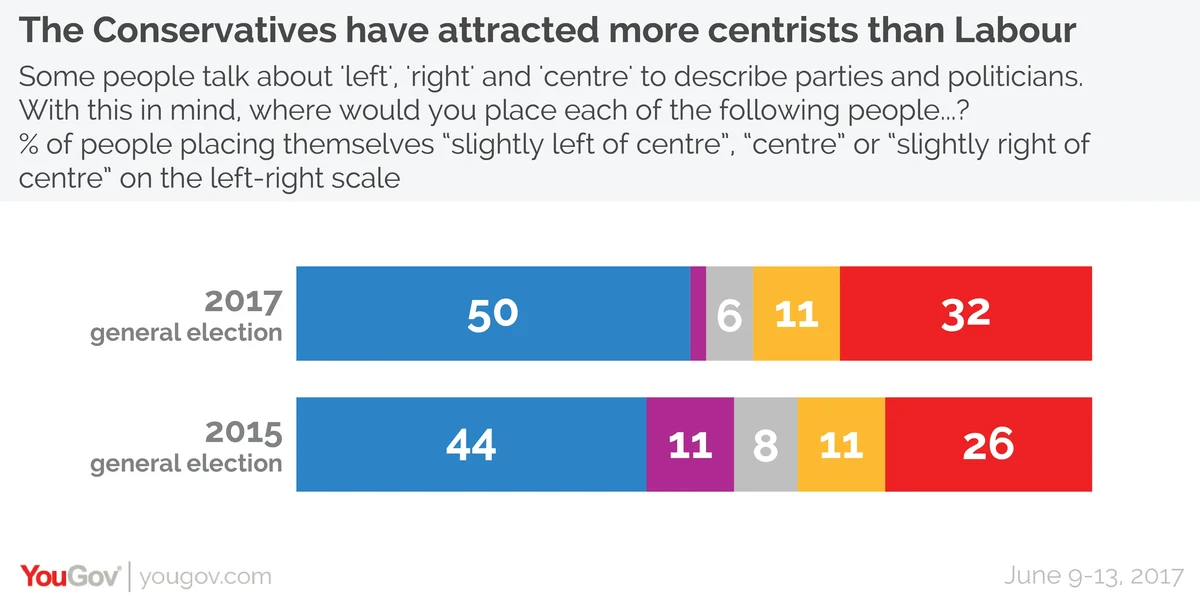

Regardless of your political beliefs, it is an arithmetical fact that the path to 10 Downing Street involves building a coalition which contains centre ground voters. Half (50%) of the public generally identify with the centre ground, saying they are “centre”, “slightly left of centre” or “slightly right of centre”. This compares to just 11% who say they are very or fairly right wing and 12% who say they are very or fairly right wing.

In this year’s general election Labour won over a few more of these “centre ground” voters than it did in 2015. Of those that voted, a third (32%) of centre ground voters backed Labour in 2017 compared to the quarter (26%) who backed Ed Miliband’s party two years ago. However, Corbyn’s party is still far behind the Conservatives who gained 50% of the centrist vote.

Our data shows that most of the “Labour surge” in June came from maximising support from the left, meaning there are few new votes to be found there. Simply put, in order to become Prime Minister, Jeremy Corbyn will now need to win over more people from the centre.

But is the Labour leader correct about where the centre ground in British politics currently is?

Firstly, as YouGov’s research has consistently found, many of Corbyn’s policies are popular. When we tested various positions immediately after he became leader we found a majority (80%) of voters supported increasing the minimum wage, introducing a form of rent caps (74%), and increasing corporation tax (51%).

On nationalisation, our poll during the election campaign showed the public thought that many institutions should be run by the public sector, including the Royal Mail (65%), the railway companies (60%), the water companies (59%), and energy providers (53%).

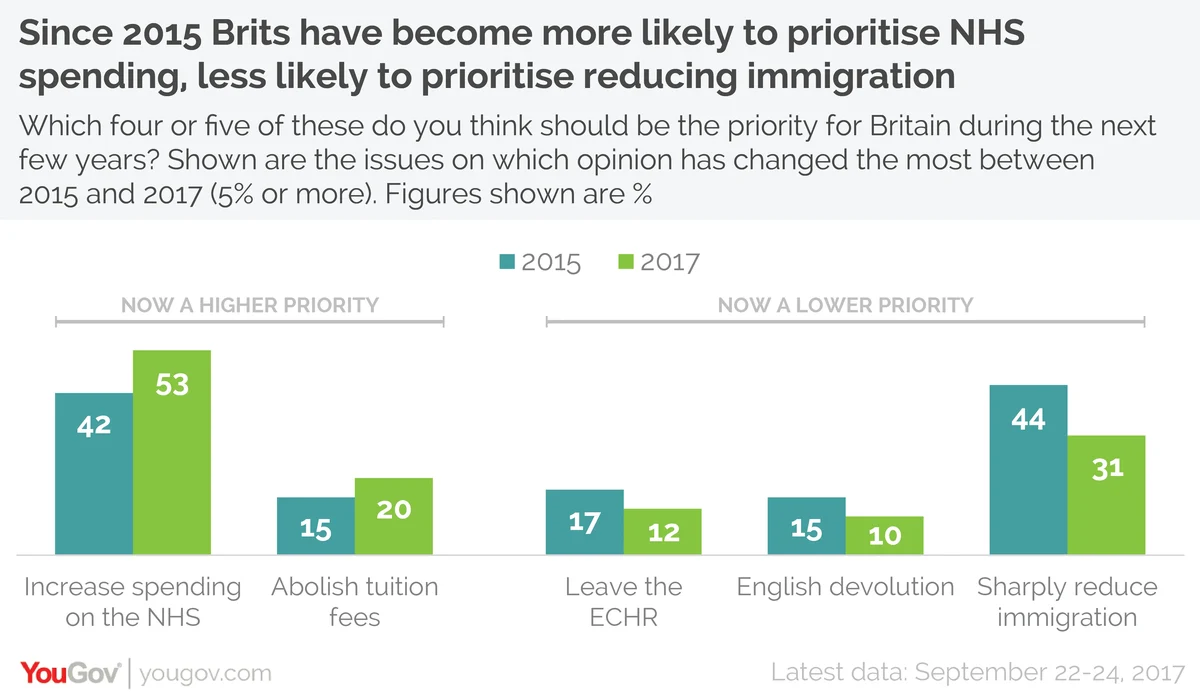

Also, since Corbyn became leader, the policy areas where the majority agree with Labour are increasing in importance among the public.

In the week Jeremy Corbyn became Labour leader in September 2015, we showed respondents a list of policies from across the political spectrum and asked them which four or five they would like to be priorities over the next few years. When we asked that same question again this week, the biggest increases had been “abolition of tuition fees for students at university” (up from 15% to 20%) and “increase spending on the National Health Service” (up from 42% to 53%), making it the most popular policy.

Meanwhile the biggest decrease has been on a policy that was the party’s Achilles heel in the 2015 election – immigration. Two years ago, “sharply reduce immigration” was the highest policy priority on 44%, but this has now dropped into third place (on 31%) behind “increase spending on the National Health Service” and “build more affordable homes” (on 36%).

So many of Labour’s policies are appealing and also seen as being priorities, which begs the question: why did they not gain the support of more centrist voters this time around?

The answer is that elections aren’t just about where the centre ground is on policy, but also where they are on leadership and competency. Even at the peak of Corbyn’s popularity in the days before polling day, more centrist voters thought Theresa May would make a better Prime Minister (39%) than thought Jeremy Corbyn would (30%). Furthermore, when we tested Labour’s manifesto during the campaign, nearly half (43%) of centrists thought that whilst Labour “had lots of policies” “they don’t seem very well thought through”.

This will be the key challenge for Jeremy Corbyn over the next few years. He is right that elections are won among centrist voters, and also correct that many of his policies are popular there. But it is not enough for the centre ground to be convinced on his policies, they also still need to be convinced in his ability to be Prime Minister.

Photo: Getty