How the YouGov method avoids errors introduced by people’s faulty memories

How did you vote at the last General Election? This should be a simple question, and easy to answer correctly. You would expect people to remember, wouldn’t you?

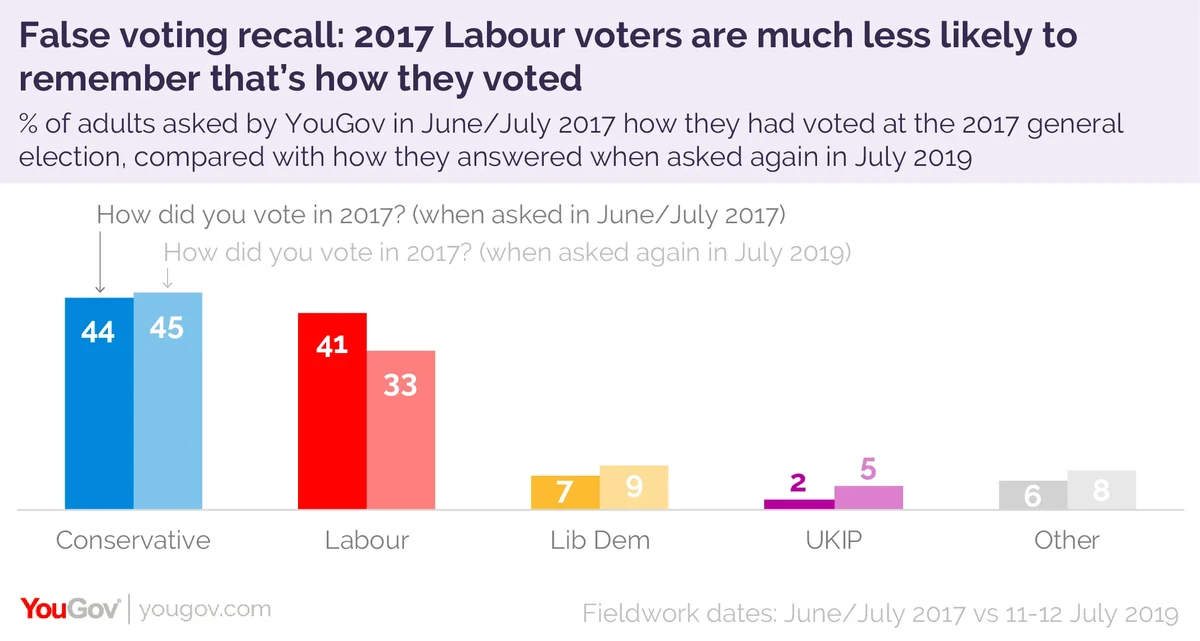

Below are the answers that a single group gave. Each of the columns on the left is the response in the fortnight after the election, when their vote was fresh in their mind (or for newer recruits, when they first joined the YouGov panel). The columns on the right are how that exact same group answered the same question last week.

The difference between the answers is stark: seven percentage points fewer people now recall having voted Labour at the last election, with a slight increase in the percentage of people claiming they voted for the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, UKIP or other parties.

This phenomenon isn't new. It’s a known pattern, often called “false recall”. Some respondents give the party they currently support, rather than the party they actually voted for at the last election. Some people who voted tactically give the party that would actually have been their first choice. Some people seem more likely to claim they voted for the winning party, and some people are genuinely forgetful.

For polling companies this is more than an interesting quirk. Almost all of us use how people voted at the last election as a target when designing or weighting our polling samples. Putting it simply, looking at how people voted at the last election is one of the ways we check that our polling samples accurately reflect the British population. It could really bias polling results if people are not accurately reporting it.

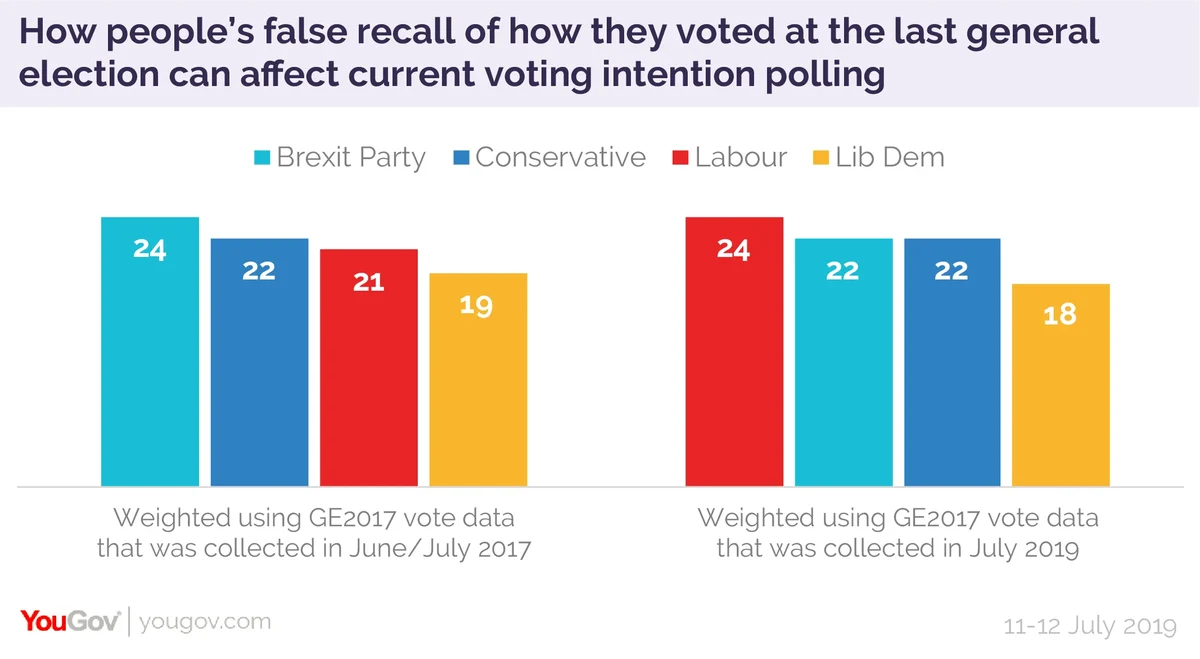

To illustrate, we asked the same respondents how they would vote now, and weighted it two different ways. On the left is the data weighted using the past vote data collected at the time of the 2017 election, and on the right is the data weighted using data collected now, which was skewed by false recall.

Both these could be described as “weighting by past vote” but how (or when) the data was collected makes three points difference to the Labour vote, changing a small Brexit Party lead into a small Labour lead.

The reason is purely that a significant number of people who voted Labour in 2017 will no longer admit it to pollsters. If polling companies ignore that and weight Labour up to their 2017 share, they risk overstating the party’s support.

How to deal with false recall used to be one of the big methodological debates within British polling. Ipsos MORI still don’t use past vote weighting at all because of their concerns over false recall. In more recent years, recalled vote seemed to be closer to reality, and it has become less of an issue. But with the recent major shifts in party support it may once again become a major concern.

At YouGov we have the advantage of a huge, well-established panel, meaning we have many thousands of people from whom we collected past vote data in 2017, before their memory had chance to play tricks on them. Many other companies do not, and must rely on asking people to recall now how they voted in 2017.

This difference may well explain some of the present variation in Labour support between different companies (I suspect it may not be coincidence that the two companies who avoided significantly overstating Labour support in the recent European elections were Ipsos MORI, who don’t use past vote weighting, and YouGov, who are able to use data collected back in 2017 for past vote weighting).

Since the aftermath of the 1992 election past vote weighting has been a key tool for pollsters trying to get a politically representative sample – but in a fluid situation like today, with the traditional main parties haemorrhaging support and new parties emerging, past vote may not be as strong a tool as in more stable times, especially given that respondents are not necessarily that good at recalling how they voted.

Photo: Getty