Jeremy Corbyn has come under fire from Labour Remain voters for supporting the triggering of Article 50. But with a third of Labour voters having backed Brexit, whatever the Labour leader does will displease many - so what approach would cause the least damage?

The EU referendum divided voters of all parties. As the party of government the Conservatives had little choice but to embrace Brexit: it was forced upon them (and in their case, the majority of their voters agreed with the majority of Britain). The number of UKIP voters who backed Remain was negligible and with a minimum of fuss the Lib Dems have identified that being the party of Remain was a route back after the near-death experience of 2015.

The vote to leave the EU has caused the most acute problems for Labour. By a solid majority of 61% to 33% its 2015 voters backed Remain at the referendum. However, the 33% of Labour-Leave voters are disproportionately the traditional working class Labour voters that the party is struggling to keep hold of. 70% of Labour Remainers are middle class, drawn mostly from the professional classes. Labour Leavers are 60% working class, mostly those working in routine occupations or surviving on benefits. Labour Remainers tend to be graduates, Labour leavers tend to have few or no qualifications.

If we break down these two Labour tribes by their current voting intention Labour's problem becomes even clearer. Amongst 2015 Labour voters who backed Remain, 60% have remained loyal to Labour and would vote for them tomorrow. When it comes to Leave voters who backed them in the last general election, only 45% would vote for the party now.

The party has lost the majority of its Leave voters. Brexit is not necessarily the cause of this problem – the distance between Labour and its traditional working class supporters was growing well before June 2016. But Brexit is the defining issue of today's politics and it risks driving a further wedge between the party and its working class voters.

So what can Labour do to try and keep these two tribes together?

Asked what the party’s position on the EU should be at the next election Labour Remainers predictably go for opposition to Brexit. Some 50% of people who voted Labour and remain want Labour to have a policy that is anti-Brexit (23% are for total opposition and 27% want a second referendum) and 30% want a policy that is in favour of Brexit.

Labour Leave voters are just as predictable – 69% want Labour to have a policy that is pro-Brexit, and either seek a purely trading relationship with the EU (46%) or a close relationship outside the EU (23%).

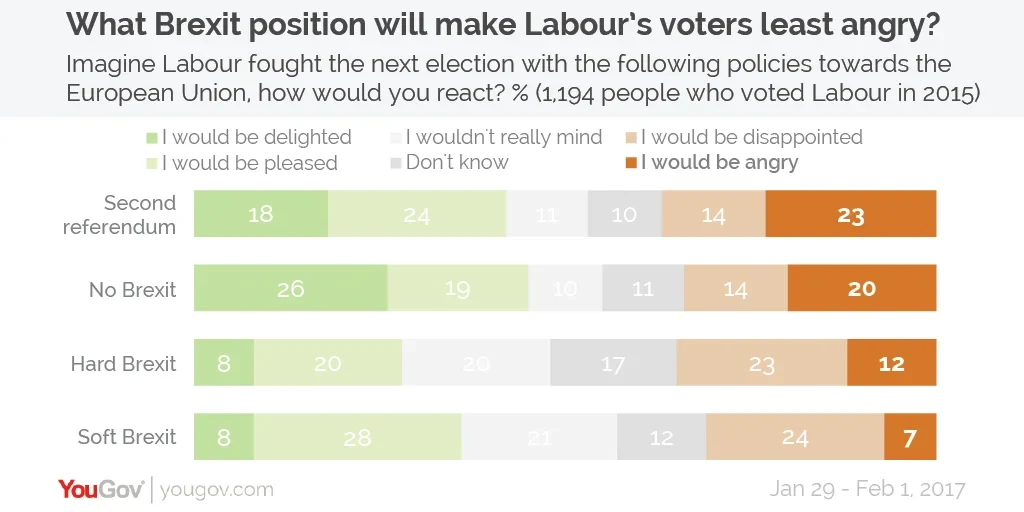

Can Labour find a policy that doesn't wholly alienate one half of its support? Just because on the surface Labour Remain and Labour Leave voters appear divided, it doesn't mean that their positions are necessarily that important to them or that they would not be willing to compromise. After asking what people's ideal policy was, we then asked how they would respond to four possible positions. We asked respondents to measure their reaction on a five point scale – seeing whether the policy would leave them delighted, pleased, not really minding, disappointed, or downright angry.

Each stance would anger some people and presumably lose some votes, but which would upset the fewest?

The most divisive policy would be for Labour to wholly oppose Brexit. 40% of Labour Remain voters would be delighted by the stance, but 55% of Labour Leave voters would be angry. Endorsing a second referendum would be viewed slightly less enthusiastically by Labour Remain voters (29% would be delighted), but would actually infuriate Labour Leave voters even more (59%).

Looking at the other extreme, if Labour promised to go ahead with Brexit and seek a trade-only relationship with the EU (essentially the Conservative government's policy) it would delight 21% of Labour Leave voters, but would anger 16% of Labour Remain voters.

The most viable compromise to keep the Labour family together appears to going ahead with Brexit, but then seeking a close relationship with the rest of the EU – a "soft Brexit" of some sort. This doesn't particularly delight either side of the divide (8% of Labour Remain voters would be delighted, 7% of Labour Leave voters), but it doesn't drive many to anger either (6% of Labour Remain voters would be angry, 10% of Labour Leave voters).

For most of Labour's voters, and most of those who say they might consider voting Labour in the future, it would be a policy they could live with. It would leave the Labour party to concentrate on issues like poverty, housing and public services where the two halves of their electoral coalition are likely to have far more in common.

Of course, for many people this will be a question of principle. If you think Brexit will be an utter disaster for Britain you may feel that Labour should oppose it to the death, regardless of the electoral consequences. Equally, it is only a snapshot in time - public opinion may turn against Brexit as the negotiations progress or if the economy turns sour, and Labour may want to gamble on being ahead of the curve.

For now, however, Labour's current position of accepting Brexit but pushing for single market membership afterwards appears to be the one likely to win the widest (if not the most enthusiastic) support.

Whatever your opinion of him, Jeremy Corbyn's leadership is not one that has been associated with triangulation or picking policy positions based on hard-nosed evaluations of what will appeal to target voters. For once, however, it appears to be the Labour leader who has picked the position that is most likely to keep the party together and alienate the fewest voters.

Photo: PA