We conducted an experiment to test current poll numbers on the EU referendum, describing opposite outcomes of Cameron's renegotiations to voters of each side. People planning to vote 'Leave' are much more likely to think again

YouGov’s latest poll on voting intention in the EU referendum shows an exact 41% to 41% tie. But what does that really mean, when we don’t know what reforms David Cameron will negotiate, how widespread skepticism about the EU contends with natural risk aversion about change, when we don’t even know when the referendum will take place?

To dig deeper, YouGov conducted a lengthy poll with a large sample – large enough to run a robust experiment with split samples in which we try to push respondents in two different directions to test the elasticity of opinion.

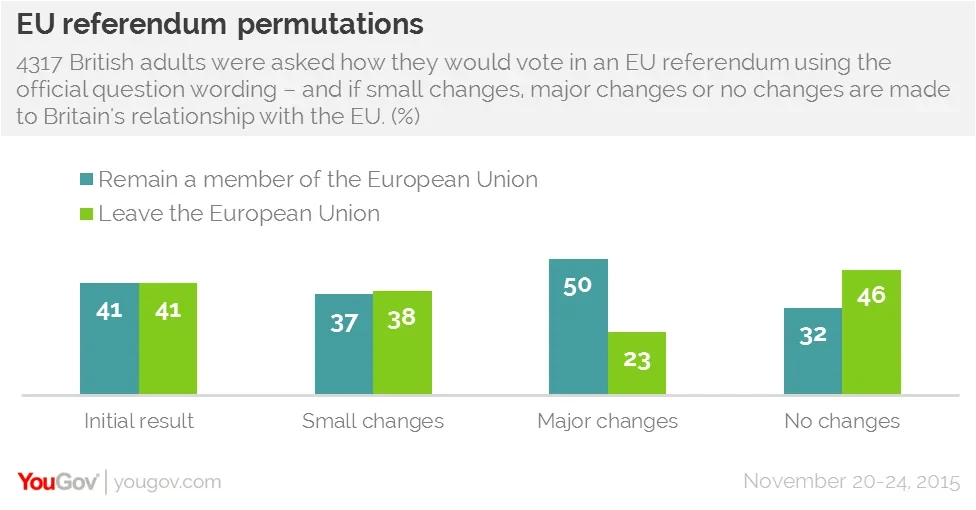

1.People say that the outcome of Cameron’s negotiations will affect how they will vote. When we ask them "Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union”, 41% say 'remain' and 41% say 'leave'. When we ask how they will vote if Cameron achieves only small reforms, it’s 37% 'remain' and 38% 'leave'. If Cameron achieves major reforms, it swings to 50% 'remain' and 23% 'leave'. If there are to be no reforms at all, it's 32% 'remain' versus 46% 'leave'. Of course we have no way of knowing how accurate these predictions of their vote will be, but they do allow us to come to some useful measures which I discuss in the conclusion.

2. Current expectations of Cameron’s negotiations are modest: most people (74%) think that he is likely to achieve only minor reforms or none at all, and this appears to be factored in to the 41%-41% headline voting intention.

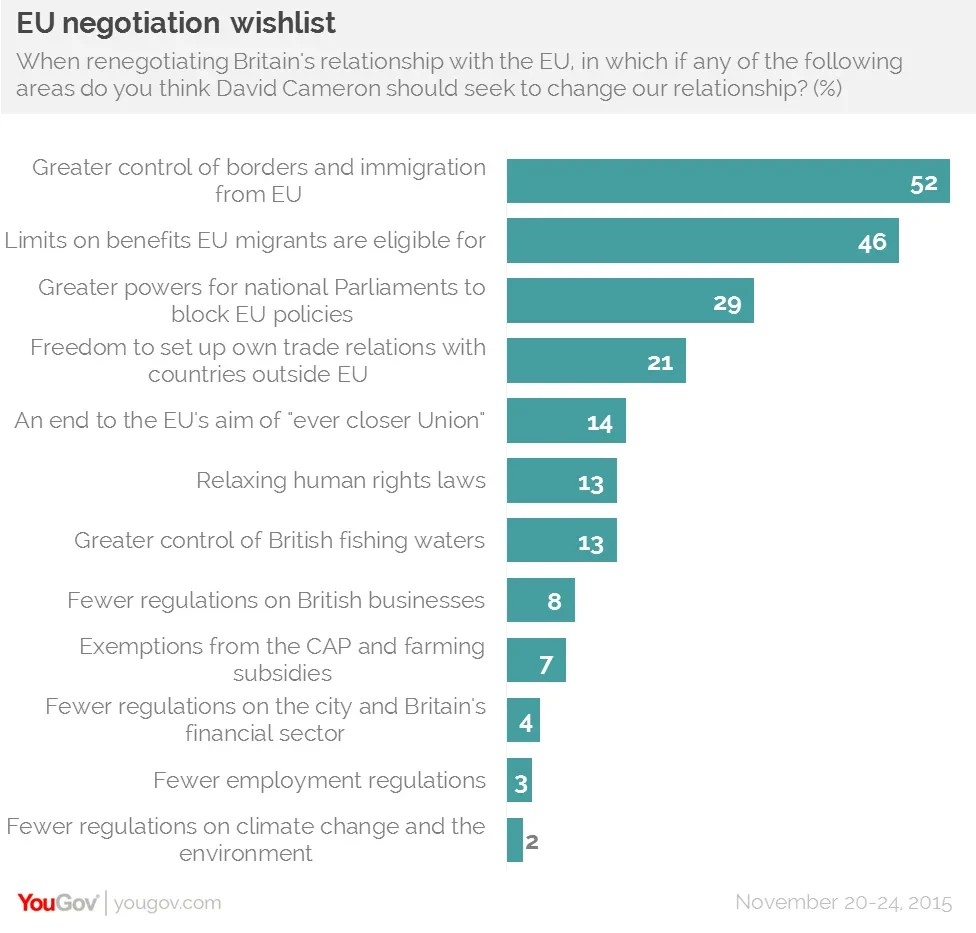

3. Immigration is the most important area for reform, with 52% listing greater control of EU immigration in their top three renegotiating issues and 46% doing so for withholding welfare benefits from EU migrants. These come a long way ahead of greater powers for national parliaments to block EU legislation, at just 29%.

4. 45% consider splitting from the EU to be risky, against 36% who think it risky to remain in the EU. 33% think they would be 'worse off' if we leave versus 27% who say 'better off'.

5. 41% think that most British business leaders are in favour of our 'staying in' the EU versus 8% who think most business leaders would prefer to leave. If senior business people were to come out and say that leaving would cost jobs and damage the economy, 39% say they would vote to stay in compared to 31% who would vote to leave.

6. More influential is if businesses are seen to be making concrete plans to close factories and move headquarters out of a UK that has split away: that produces 43% for 'remain' v 29% for 'leave'.

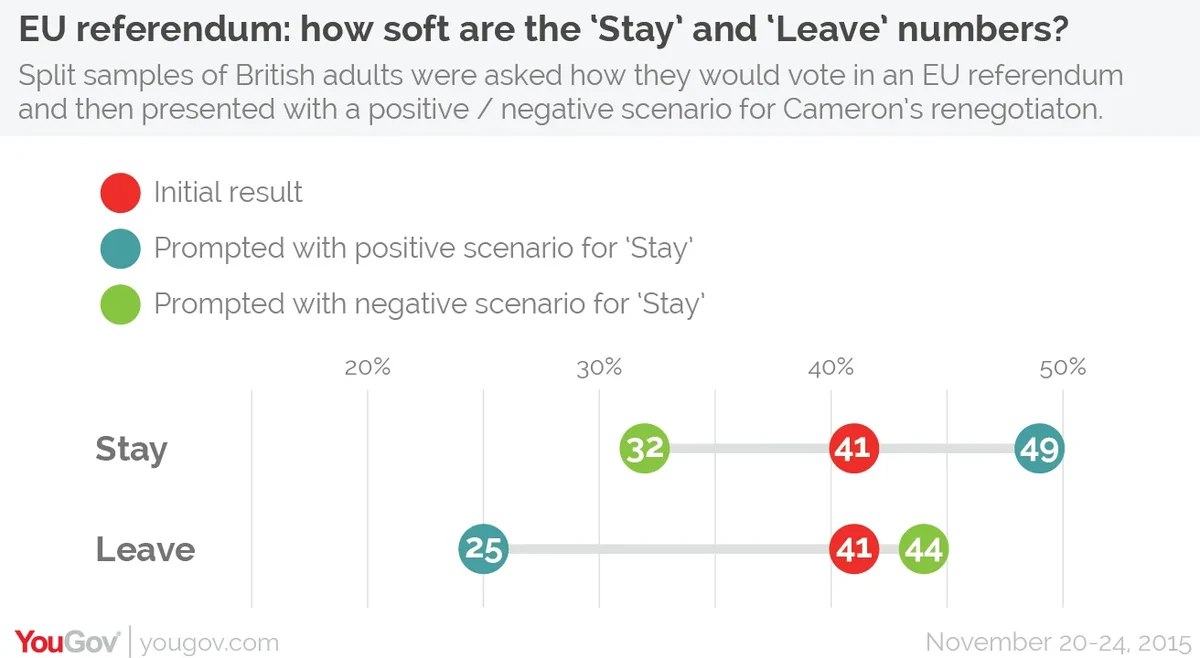

7. We randomly split the sample of 4317 into two samples. The first sample were given a very negative scenario: “Imagine that David Cameron is unable to secure a good deal in his renegotiations and that many senior political figures back calls for Britain to leave the EU. Business figures are split, but assure the public that they are committed to investing in Britain whatever the result of the referendum. Other European Union leaders say they would respect Britain’s decision if we voted to leave, and would be willing to negotiate an alternative trade deal.”. Under these conditions, people tell us, they would vote 32% say they would vote to 'remain' v 44% to 'leave'.

The other split sample was given a very positive scenario: "Imagine that David Cameron manages to sign a good deal in his renegotiations and that he and the leaders of all the main parties recommend that Britain votes to remain in the EU. Most business leaders back Britain staying, and several large employers announce plans to move operations to mainland Europe should Britain vote to leave. The European Union itself makes clear it would like Britain to stay, and there would be no option of the free trade deal if Britain did leave the EU." Under these conditions, people tell us, they would vote 49% 'remain' v 25% 'leave'.

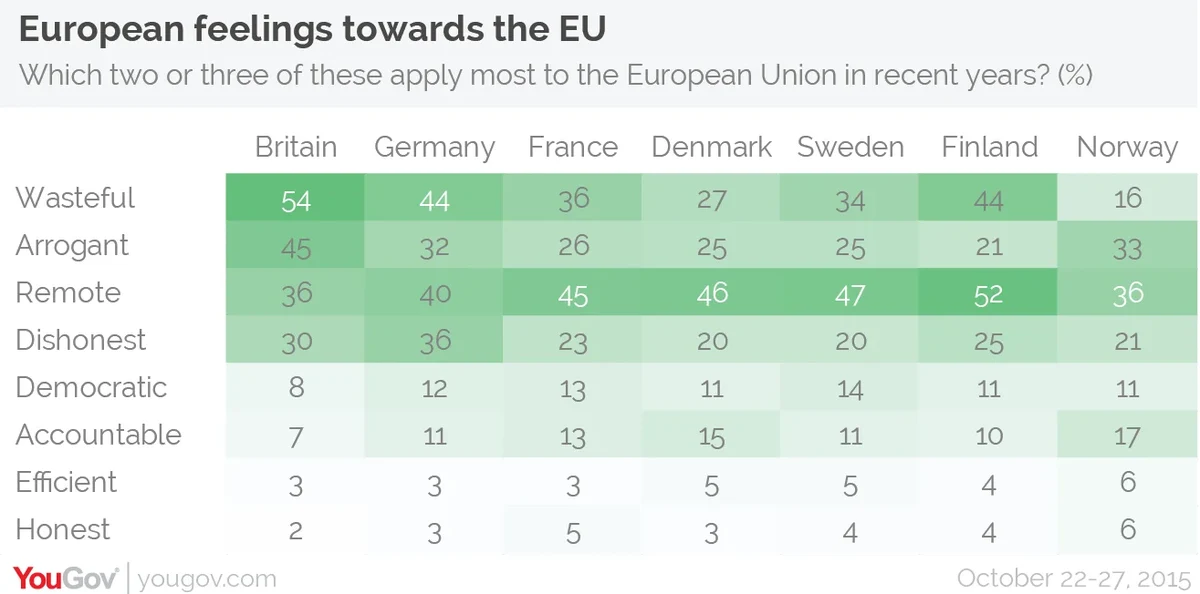

8. We also ran a separate survey to 6 EU countries (Germany, France, UK, Sweden, Finland, Denmark). Scepticism about the EU is not confined to the UK: asked to choose among four positive adjectives and four negative adjectives about the EU, all countries were far more negative than positive. The most common adjectives used to describe the EU among British respondents were 'wasteful' and 'arrogant'; among the Germans it was 'wasteful' and 'dishonest', and for the others it was 'remote' and 'wasteful'. The highest proportion to choose 'honest' for the EU was 5% from the French. The results were not dissimilar for respondent attitudes to their own governments.

A new way to report EU referendum voting intention

There is a fundamental problem in predicting the outcome of the UK EU referendum using current voting intention numbers. We don’t know how the Prime Minister’s negotiations for reform will turn out. We don’t know when the referendum will actually take place. We do know that many people are torn between the desire to express their EU skepticism, indeed their anger towards it, and their fear of change whose consequences cannot easily be predicted. We need to recognise significant potential for change in voting intention over the coming months as events, arguments and the psychological pressure of an impending historic decision play their parts.

Our experiment, trying to push samples in one direction or another, may yield a useful secondary measure. We were able to shift opinion 8% towards remaining in the EU, but only 1% towards exit. That is clearly not symmetrical. It suggests a greater likelihood of people moving toward ‘remain’ rather than ‘exit’. One might report this is 41 remain (32-49) v 41 exit (25-44). As we say, this is an experiment. In the future we will attempt other ways to push opinion, to test the limits of attitudinal change.