If the Tories want to show they are genuinely concerned for people across the income range, they still have a great deal to do

The verdict of The Economist this weekend is that George Osborne’s Budget is: ‘politically astute, economically flawed’. This blog expresses no view of the economics; but YouGov’s polling since the Chancellor unveiled his measures suggests that the praise for his political acumen may be premature

We have conducted two surveys: one in the first 24 hours of the Budget, on the public’s immediate reaction to Osborne’s measures; the other a day later, on Thursday evening and Friday morning, after voters had had more time to digest the Budget’s implications. We can divide the results into the good news for Osborne, the so-so news and the bad news.

The good news:

- 80% of voters support the proposed living wage, of £7.20 an hour from next year, rising to £9 by 2020.

- Raising the personal tax allowance is also immensely popular, backed by 84%.

- By 67-20%, voters approve of restricting child tax credits in future to the first two children in each family.

- By an identical margin, we approve of the reduction in the total amount of benefits per household to £23,000 a year in London and £20,000 outside London.

- By two-to-one, we back the commitment to spend at least 2% of national income on defence.

The so-so news:

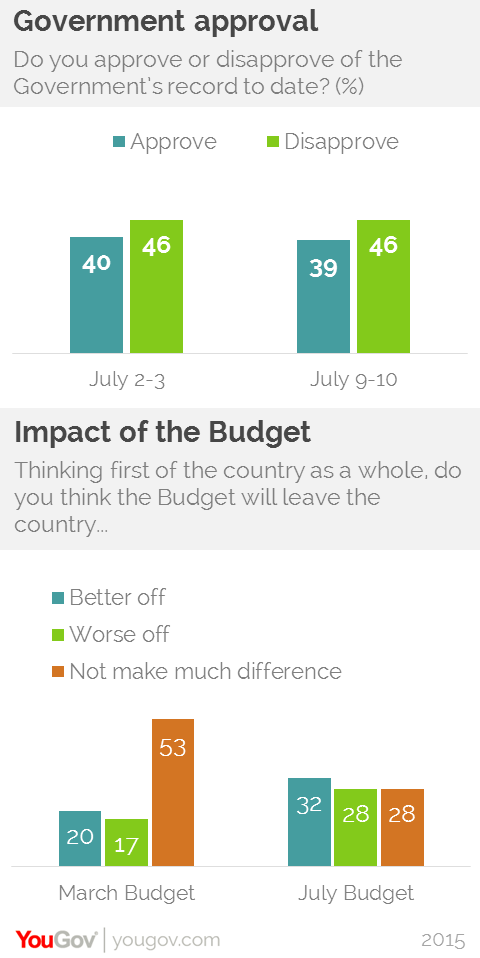

- The Budget has had little impact on the ratings of the Government or Osborne himself. Overall, 39% approve of the Government’s record to date, while 46% disapprove. This is exactly the same as last week. Osborne’s personal ratings are much the same as they were after his pre-election Budget four months ago, with 43% now saying he is doing well and 45% badly.

- We divide fairly evenly on the impact we expect the Budget to have on Britain as a whole, with 32% saying better off, 28% worse off and 28% no difference. After March’s Budget, by far the biggest number, 45%, expected the measures to make no difference; among the rest, people were significantly more likely to expect things to get better (26%) than worse (17%).

- There is more hostility to imposing a cash freeze on in-work benefits than to other welfare reforms. 46% support the change, while 36% oppose it.

The bad news:

- Two of Osborne’s specific measures are unpopular: abolishing maintenance grants for students with low income and replacing them with larger loans (opposed by 52-24%) and limiting pay rises for public sector workers to 1% a year for the next four years (opposed by 51-30%).

- More people think the Budget will leave them worse off than better off (although half of all respondents say it will make little difference to them). In March, slightly more people thought they would be gainers rather than losers.

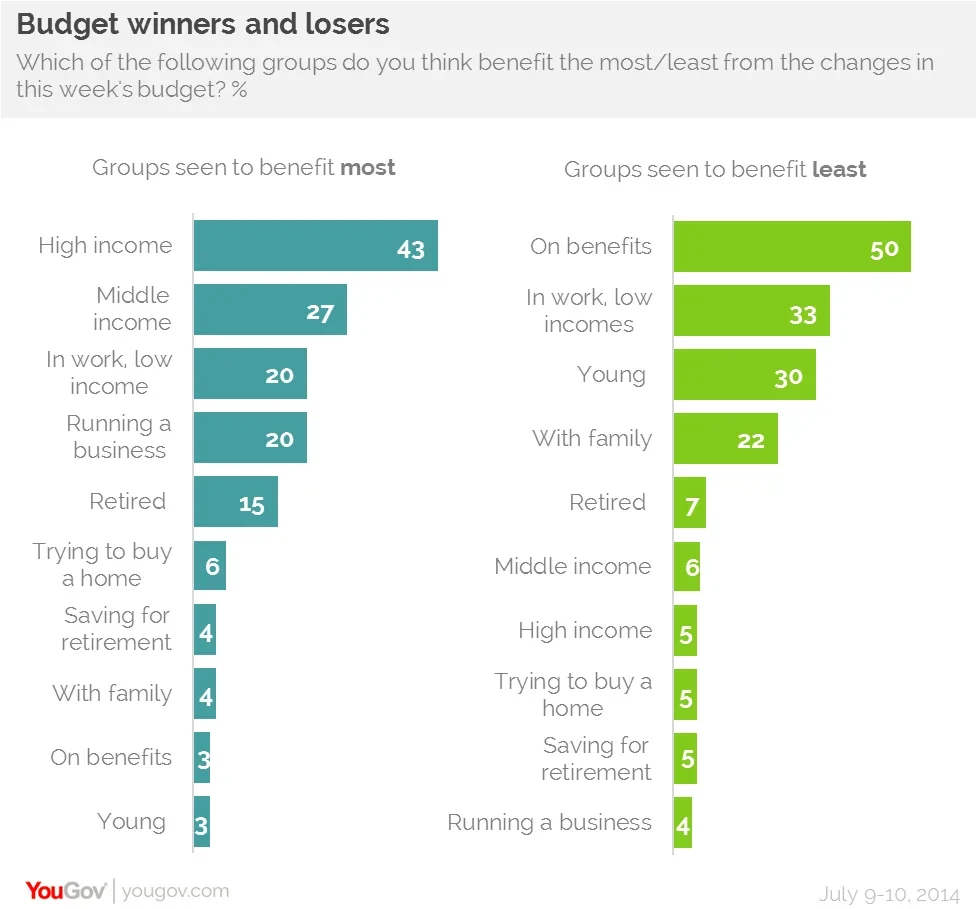

- Osborne has failed so far to persuade voters that his is a ‘one-nation’ Budget. We offered a list of ten groups of people and asked which two or three had (a) benefited MOST from the Budget and (b) which had benefited LEAST. Each produced a clear ‘winner’, with people on high incomes widely thought to have gained the most, and people on benefits having gained the least. Other groups widely regarded as losing out are: ‘people in work but on low incomes’, young people and people with families.

- Few voters back Osborne’s strategy of reducing benefits for people who are in work but on low wages. Just 12% think too much is spent on this group, compared with 45% who think too little is spent on them. More popular targets are ‘people who are out of work’ and, most popular of all, ‘better-off retired people’. This last group (interest declared: I am one of them) has not just been protected from austerity since Osborne became Chancellor in 2010; the triple-lock on state pensions means that they – we – are now treated more generously by the Government than ever before.

Taking all these findings together, we must wait, perhaps until close to the next general election, before we can say definitely whether this week’s Budget is a political success.

In narrow winner-and-loser terms, few Conservative voters are likely to suffer significantly. The Tories have already alienated a fair number of public sector workers and those on low incomes. The rise in the personal tax allowance, and the promised steady rise in the higher-tax-rate threshold towards £50,000, could prove popular in the middle-income suburbs that tend to decide elections.

On the other hand, this Budget seems, initially at least, to have set back the manifest ambition of both Osborne and David Cameron to reposition the Conservatives as a one-nation party. The Tory brand is still tainted. The Prime Minister has yet to persuade enough voters that ‘we are all in this together’.

By the time the Tories face voters in 2020, this might have changed – and, if it has not changed, it might not prevent another Conservative victory, if the economy grows (perhaps boosted by supply-side changes to apprenticeships and planning regulations), if general living standards rise, if the planned changes to Commons constituency boundaries go through and if Labour still lacks credibility as an alternative government. And maybe Budgets in the next four years will do more for working families who struggle to make ends meet. But if the Tories really do want to show that they are genuinely concerned for people across the income range, they still have a great deal to do.

PA image