Over the last few months we’ve seen a shift in headline voting intention away from the Conservatives towards the Labour party. The latest YouGov/Times voting intention poll, conducted on 12-13 January, shows a 11-point lead for Labour, their biggest since 2013. This is an increase from a four-point Labour lead last week, and marks 13 weeks of general decline in the Conservatives’ vote share since mid-October.

General elections only count those who actually cast a ballot, and so it is too with voting intention polls. The figures shown in headline voting intention polls only show the vote among those who know which party they would cast their ballot for, and exclude those who either do not intend to vote or who have not yet made up their mind who to vote for.

Sometimes, however, it can be useful to look at these undecided voters to learn more about the wider voting landscape.

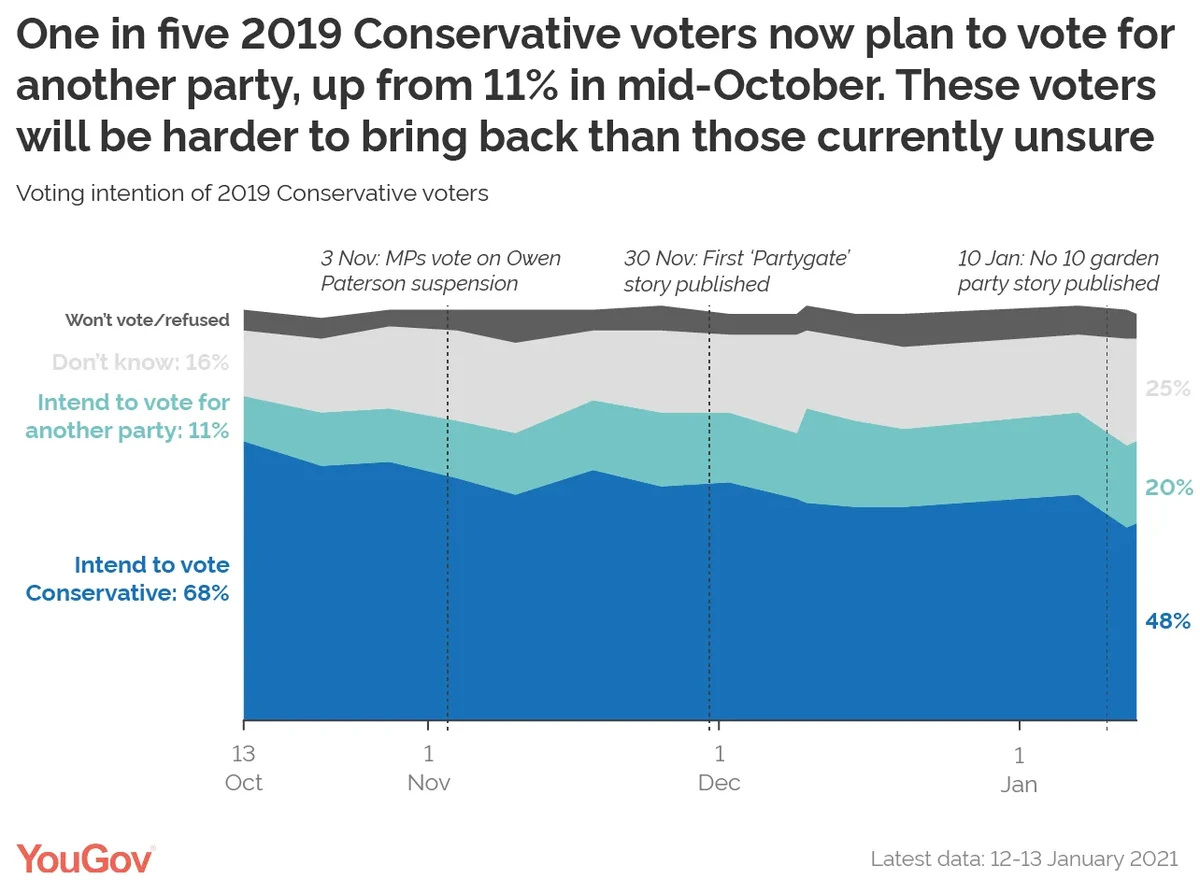

Currently, a quarter of 2019 Conservative voters (25%) say they are unsure how they’d vote if there was an election tomorrow, up six points from last week when 19% said the same. In contrast, just 11% of 2019 Labour voters say they don’t know how they’ll vote, virtually unchanged since the week before.

This difference in don’t knows between 2019 Tory and Labour voters has a big impact on the change in the headline voting intention. Because so many 2019 Conservative voters are dropping out of the pool of people who count towards the headline voting intention figures, this means that those Conservatives remaining with the party make up a smaller proportion of the whole voting intention electorate. This shrinks the Tory vote score, even though none of this specific group have shifted over to Labour or the other parties.

While clearly this is not a good situation for the Conservatives, there is some small comfort: past voters who have moved to being undecided are often easier to win back than those who move elsewhere.

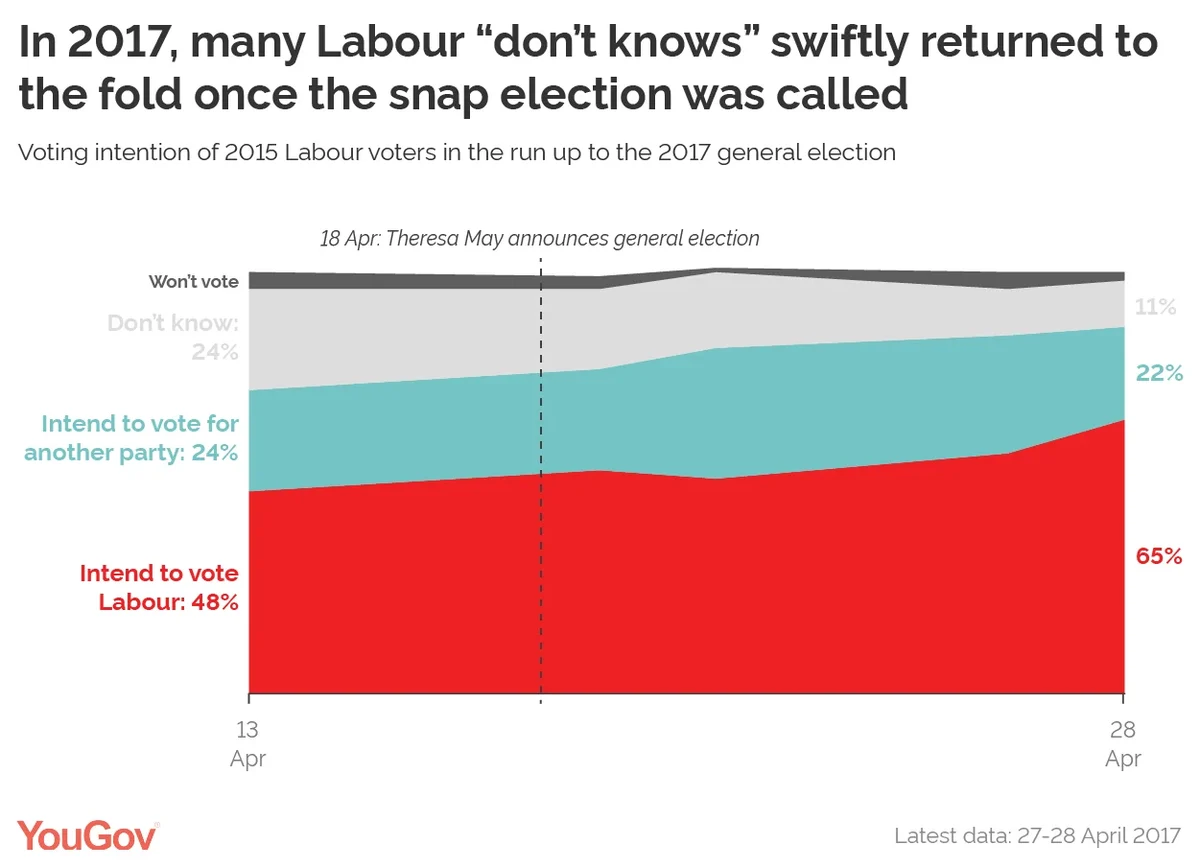

‘Don’t knows’ tend to return to their previous party when the election comes round

A historical illustration of this was in 2017, following Theresa May’s announcement of a snap election. The week prior to her press conference, the Conservatives had a comfortable 21-point lead over Labour.

At this point a quarter (24%) of 2015 Labour voters said they did not know who they would vote for, with just half of this group (48%) saying they’d stick with Labour. But with the reality of a general election having set in, by the time of a YouGov poll two weeks later the number of 2015 Labour voters saying they didn’t know how they’d vote had dropped to just 11%. Virtually all of this shift was people returning to Labour, with their retention increasing from 48% to 65%.

The Tories had lost far fewer of their 2015 voters to the ‘don’t know’ column so they had fewer to bring back into the fold. Over that two-week period the headline Conservative vote lead over Labour fell to 13 points, largely because of the greater number of unsure Labour voters coming back to the party.

As the campaign progressed, the difference in don’t knows evened out for Labour and Conservative past voters. The further narrowing of the lead to an eventual 3 points was therefore down far more to party switching in what was a particularly turbulent election campaign.

The Conservatives should be more worried about voters they are losing to other parties

We should therefore be cautious about this week’s change in vote share immediately following the latest Downing Street party controversy, as much of it may be less concrete than it first appears.

The bigger concern for the Conservatives is those who are moving away from them to other parties – a shift that has also been taking place over the last few months.

At the start of October, 12% of 2019 Conservative voters said they’d vote for a different party, but this number has now risen to around 20%. These voters are moving both to the left and the right, with 9% now saying they’ll go to Labour, 3% to the Lib Dems and 7% to Reform UK, among other parties.

This is not to say these voters won’t return (particularly those shifting to smaller parties) but they do tend to be stickier than those who switch to being undecided.

Pivotal to Boris Johnson’s success in 2019, was his ability to win over voters directly from Labour in the early months of his premiership, without his own voters going the other way. When he took over in July 2019, just 2% of previous Labour voters said they’d vote Conservative. The party managed to increase this to 7% ahead of the election being called and kept hold of these voters at the ballot box in December.

While it’s pretty clear that the last few months have been damaging for the Conservatives, we don’t yet know whether these losses represent short term disapproval of the party or longer-term electoral change. The most likely reality is that it is a little of both.