It is rare for the unconnected events of a single day to throw light on huge changes seemingly taking place in world history. But Tuesday of this week may have been such a day.

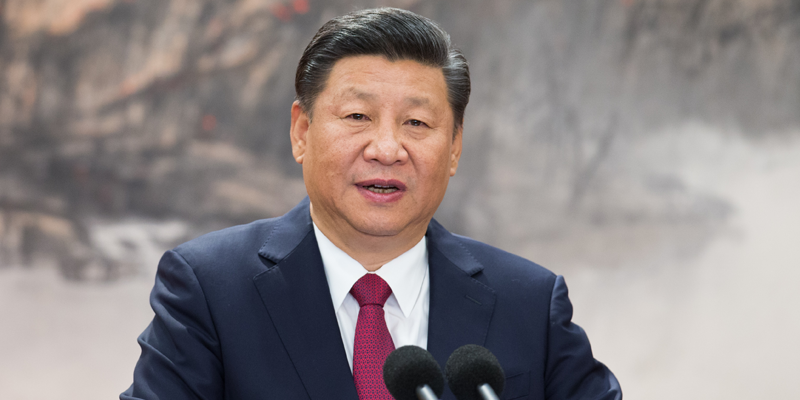

In Beijing, Xi Jinping was confirmed as the most powerful leader of the Chinese Communist Party since Mao Zedong and announced that this ‘new era’ will bear his name, China will be much more assertive on the world stage. Meanwhile, in Washington, the leader of the West, President Donald Trump, was denounced by leading members of his own party as ‘an utterly untruthful president’ responsible for ‘the regular and casual undermining of our democratic norms and ideals’. Do these events mark the inexorable rise of China and the inevitable decline of the West? And if so, should we be scared?

Xi Jinping’s grip on power in China now seems total. He is the only leader since Mao to succeed in changing the constitution of the Chinese Communist Party during his own time in office in order to define a doctrine in his own name. That doctrine, with its grabby title of ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese characteristics for a New Era’ may not seem earth-shattering, but it means that Mr Xi cannot be attacked without such an attack implying criticism of the party itself. And that is absolutely forbidden in China.

What’s more, by declining to follow the recent practice of appointing someone in his fifties to the all-powerful standing committee of the party’s politburo, Mr Xi has refused to anoint a successor. That is taken to mean that he will break with custom and serve a third term into his seventies.

The message for the rest of the world is that China wants to start flexing its muscle. The previous dominant ideology, brought in during the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, was essentially economic. The Chinese economy would open itself to the world and, despite continuing forelock-tugging to ‘socialism’, would be run on capitalist lines. But Deng was clear that China was not yet ready to become a superpower and throw its weight about in the world.

This is what has now changed. China has already built up huge economic influence in the world through its buying up of western companies, its infrastructure building programmes in developing countries throughout the world, and its massive penetration of western consumer markets via its export drive. Now Mr Xi, looking forward not just five but thirty years, sees China converting that economic power into political clout.

It is not that Mr Xi wants China to expand territorially: it has quite enough land (and people) as it is. Rather, he wants to export the Chinese model of government, the better to protect China’s power and influence in the world. He sees China’s form of government, based on the absolute power of the Chinese Communist Party over all aspects of the state, as a model providing ‘a new option for other countries and nations’. That model involves the tightest control over political activity, now enhanced by cyber controls that can track the postings, the faces, the purchases and the movement of China’s population. The internet is tightly regulated and the access of western media is greatly curtailed. For the first time, prominent western media organisations such as the BBC, were excluded from this week’s party conference.

In short, the price of China’s ‘success’ is the political and media freedom we take for granted in the West.

But here in the West, many political leaders are beginning to look diminished figures compared with the almighty Xi. At the very moment he was confirming his grip, Donald Trump was under unprecedented attack for an American president by senior senators in his own party. Announcing his decision not to run for re-election, Republican Senator Jeff Flack of Arizona, accused Mr Trump of ‘reckless, outrageous and undignified behaviour’ and of ‘flagrant disregard for truth or decency.’ He said the President was trying to transform US citizens into ‘a fearful, backward-looking people’.

His colleague, the even more senior chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee, who has also decided to retire, said Trump ‘has great difficulty with the truth’, adding that world leaders, including America’s long-standing allies in the West, don’t trust him because they are ‘aware that much of what he says is untrue’. Mr Corker said of the President: ‘He purposely is breaking down relationships we have around the world that have been useful to our nation, but I think at the end of the day, when his term is over, I think the debasing of our nation, the constant non-truth-telling, the name-calling … will be what he will be remembered most for.’

The White House hit back by saying that these were just the words of failed leaders of a Republican Party old guard who had decided not to run again because they realised they would be dropped by the party itself if they tried. Nonetheless, their outspoken hostility will do nothing to help a president already accused of having failed to deliver much since he came to power: their two votes will potentially deprive the President of his party’s majority in the Senate, making continuing paralysis in government even more likely.

But if America’s problems might seem localised around its current leader, the leadership of the West looks barely more promising. Europe would hardly appear to be in a position to take up that leadership role while Washington is preoccupied with throwing mud at itself.

Brexit, for all its dominance of British politics, is not even the greatest of the European Union’s headaches. Spain, one of its most populous members, seems on the brink of tearing itself apart, possibly violently. Recent elections throughout the union, including in its most important member, Germany, have revealed a rise in nationalist opinion that is often hostile to the EU itself. And the abiding, unresolved issues of the sustainability of the Eurozone and mass immigration add to the sense that the EU will have its work cut out simply pulling through, never mind trying to take up the baton of Western leadership against an increasingly assertive China.

Of course there is a wholly different way of looking at these events. The hubris of Mr Xi could simply be the prelude to nemesis. The old hypothesis, that a ‘capitalist’ economy as successful as China’s is ultimately incompatible with political repression, remains to be disproved. Tight control may one day trigger revolt, as it threatened to do back in 1989. Less apocalyptically, though no less dangerously, Mr Xi’s apparent attempt to entrench and extend one-man rule, may end in tears.

Equally, what may appear to be turmoil and paralysis in America, and enforced navel-gazing in Europe, could instead be interpreted as democracy doing exactly what it is supposed to do. Joseph Schumpeter, the great Austrian economist, spoke of the necessity of ‘creative destruction’ in capitalist economies; the same term might be applied to democratic politics. Certainly, Mr Trump’s supporters would argue that whatever his critics might say about his style of government, his election showed his capacity to activate voters who had come to the conclusion that the democratic system offered them nothing. Now they have a voice. Similarly, Europe’s travails at least indicate responsiveness to changing public opinion, the very thing democracy is supposed to provide and which rule by one party finds so difficult.

So what are we to make of the unconnected events of this week? Do they illustrate an unambiguous shift in world politics, with the democratic west in decline and the authoritarian model of China in the ascendancy, or is it too soon to be sure? And if that is what is going on and the world starts to turn its back on democracy in favour of strong government that is unembarrassed by stifling freedom and democracy, should we worry?

Let us know your views.

Image: Getty