British public opinion on drones and targeted killing has been oversimplified; Britons are divided on whether current drone policies are ultimately helping or hindering Western security, but there’s also a distinction between attitudes to the weapon and the way it’s used, which go beyond binary moral judgements about ‘drones-good’ or ‘drones bad’.

Doctrine and technology are like the ’chicken and egg’ of military history. It’s hard to know, for example, what came first in Washington: the decision to modify unmanned surveillance aircraft with Hellfire Missiles or a new doctrine for remote controlled killing in the military no-go atlas of the global south.

Either way, an unofficial US drone programme stayed largely free from official debate for years after November 2002, when US President George W. Bush authorised the first 'targeted killing' with an unmanned aerial ‘drone’ in the skies over Yemen.

Until recently, that is, as leaked memos about secret US drone hubs in Saudi Arabia and White House hush-deals with the media have combined with a growing, cross-country chorus of concern towards the death toll of non-combatants, the violation of sovereignty made logistically easy, and the whole notion, accurate or otherwise, of Western political leaders with an armchair power of execution.

As public debate now catches up with a ten-year old policy, and since it was recently reported that the UK Government might be passing information to US authorities to help them carry out drone missile strikes in countries like Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, it’s fair to say that British public opinion on the subject has been variously oversimplified on a scale between nonchalantly for and hysterically against.

In support of a recent Whitehall Report on drone warfare, YouGov conducted a multi-stage study of British attitudes to the use of drones and targeted killing, including six surveys between 26 February and 8 March, 2013, with a nationally representative poll of 1,966 British adults and several survey experiments looking at different scenarios, involving at least 700 respondents in each case. (See full details of results and methodology at the bottom of this post.)

According to results, the British public are broadly divided on whether the current use of drones is ultimately doing more harm or good to Western security. But there’s also a distinction between attitudes to policy and the weapon itself, which go beyond binary judgements about ‘drones-good’ or ‘drones bad’. Findings show notable public concern, for instance, towards civilian and political costs of drone warfare, and the possibility that it makes foreign intervention too easy. But a majority of respondents also support the policy, at least in principle, of targeted assassination or extrajudicial killing using drones. Many Britons further perceive benefits, as well as dangers, in the precision strike capability that drones provide, such as reducing civilian casualties.

Potential Impact of Casualties on Support for Drone Strikes

For the first part of this report, YouGov conducted five experiments designed to explore how public support for government involvement in drone strikes might be affected when several independent variables are introduced, including the context of imminent threat, the targeting of UK citizens and the likelihood of varying civilian casualties.

Each survey was fielded to a different, nationally representative survey of the adult British population, including at least 1,500 respondents respectively.

In each case, respondents were first shown the following explanatory text:

It was recently reported that the UK Government might be passing information to US authorities to help them carry out missile strikes from unmanned aircraft called ‘drones’ to kill known terrorists overseas in countries like Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia.

People were then asked to what extent they would support or oppose the UK government assisting in a drone missile strike. In each case, however, we asked about a slightly different scenario, and also split the sample into two roughly equally sub-samples. In the second sub-sample, we asked yet another version of the question, this time with an added element, asking respondents to imagine the missile strike were intended to prevent an imminent threat to Britain. (Of this, more later.)

Table 1 shows the overall results from each of the first sub-samples. (See Notes on Methodology at the end of this essay for more details on Surveys 1–5)

Table 1: ‘To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose the UK Government assisting in a drone missile strike…’

| Support(%) | Oppose(%) | Don’t know(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas?’ (n=883) | 55 | 23 | 21 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if the person being targeted were a UK citizen?’ (n=871) | 60 | 23 | 17 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were guaranteed that no innocent civilians would be killed by the drone strike?’ (n=933) | 67 | 21 | 13 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were likely that 2–3 innocent civilians might be killed by the drone strike? (n=953) | 43 | 41 | 16 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were likely that 10-15 innocent civilians might be killed by the drone strike? (n=802) | 32 | 46 | 22 |

In these results, an overall majority of 55% said they support versus 23% saying they oppose in response to the basic version of the question: ‘To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose the UK Government assisting in a drone missile strike to kill a known terrorist overseas?’

Among the camps of current voters for the three big political parties, a strong majority of Conservatives said they support (75% vs 9% oppose); as did roughly half of Labour (52% vs 29% oppose) and a smaller plurality of Lib Dems (43% vs 36% oppose).

Overall support for assisting in a missile strike increases slightly to 60% when the question includes the added detail of: ‘if the person being targeted were a UK citizen’ – potentially, we might guess, by implying a more direct threat to Britain – as does support among Conservative and Lib Dem voters. (Respectively: Cons – 79% support vs 11% oppose; Lab – 49% support vs 31% oppose; Lib Dems – 56% support vs 38% oppose.)

Perhaps predictably, support increases again to 67% overall, including majorities in each of the big parties, when the question includes: ‘if it were guaranteed that no innocent civilians would be killed by the drone strike’. (Respectively: Cons – 85% support vs 12% oppose; Lab – 61% support vs 24% oppose; Lib Dems – 59% support vs 33% oppose.)

We then see that overall support for a drone strike drops substantially to 43% when the suggestion is introduced that two or three innocent civilians might be killed. The overall number of those who oppose rises to a roughly similar 41%, and the electorate becomes essentially divided.

Overall support for a drone strike drops further still to 32% when the suggestion is introduced of larger casualties, with 10–15 innocent civilians possibly killed. The overall number of those who oppose rises to a larger 46%, meaning a plurality is now against the strike.

It should be noted in these figures, however, that sensitivity to casualty rates is not uniform across the political spectrum.

When asked the question including a casualty-rate of two or three innocent civilians, Labour and Lib Dem supporters show majorities – just about – who oppose, while a substantial majority of Conservative supporters (62%) still support the missile strike. (Respectively: Cons – 62% support vs 26% oppose; Lab – 38% support vs 50% oppose; Lib Dems – 36% support vs 51% oppose.)

In response to the question including a larger casualty rate of 10–15 innocent civilians, Conservative supporters become broadly divided, while a plurality of Labour and majority of Lib Dem supporters are opposed. (Respectively: Cons – 40% support vs 45% oppose; Lab – 31% support vs 45% oppose; Lib Dems – 30% support vs 53% oppose.)

Potential Impact of an Imminent Threat on Tolerance for Casualties

In the second sub-sample of each survey, however, we also found that sensitivity to casualty rates is potentially impacted across the political spectrum by the independent variable of imminent threat.

As previously explained, in each of the five experiments, we also split the sample into two roughly equal sub-samples. In the second sub-sample, we asked a slightly re-worded version of the question in each case, but this time with an added element, asking respondents to imagine the missile strike were intended to prevent an imminent threat to Britain.

Table 2 shows the overall results from second sub-samples.

Table 2: ‘Imagine a terrorist attack against the UK was imminent and could be stopped by a drone missile strike against a known terrorist in Yemen. To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose the UK Government assisting in a drone missile strike…’

| Support(%) | Oppose(%) | Don’t know(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas?’ (n=878) | 74 | 14 | 12 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if the person being targeted were a UK citizen?’ (n=856) | 71 | 12 | 17 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were guaranteed that no innocent civilians would be killed by the drone strike?’ (n=973) | 75 | 11 | 14 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were likely that 2-3 innocent civilians might be killed by the drone strike? (n=912) | 64 | 20 | 15 |

‘to kill a known terrorist overseas if it were likely that 10-15 innocent civilians might be killed by the drone strike? (n=723) | 60 | 22 | 17 |

In this context, overall support remains notably less sensitive to casualty numbers. We see support for a missile strike drops from 75% to 64% among respondents overall when asked the question with a casualty rate of two or three innocent civilians instead of none, and drops further to 60% when it includes a casualty rate of 10–15 innocent civilians.

Clearly, it should be remembered that an opinion survey of attitudes to hypothetical scenarios is different from measuring public reactions to a real event. Notwithstanding, in each case, overall support retains a strong majority. Responses further show majority support for a missile strike among all three big political camps in both casualty scenarios.

When asked the question including a casualty-rate of two or three innocent civilians, results are respectively: Cons – 83% support vs 9% oppose; Lab – 61% support vs 24% oppose; Lib Dems – 68% support vs 22% oppose.

When asked the question including a casualty rate of 10–15 innocent civilians, results are respectively: Cons – 88% support vs 12% oppose; Lab – 58% support vs 26% oppose; Lib Dems – 53% support vs 33% oppose.

Attitudes to the Policy/Principle of Targeted Killing

For the second part of this study, YouGov fielded a longer, single survey to a nationally representative sample of British adults (n=1,966), looking at broader perceptions surrounding the drone debate. (See Notes on Methodology at the end of this essay for details on Survey 6.)

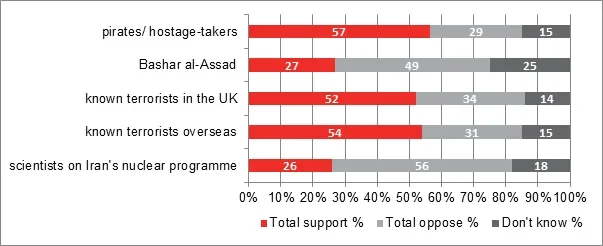

Before looking specifically at attitudes to drones, we tested attitudes more generally to the policy of targeted killings. As Figure 1 shows, respondents were asked to what extent they would support or oppose their government taking part or assisting in various examples of targeted killing.

Figure 1: ‘To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose your country's government taking part or assisting in each of the following? (Assassinating…)’

Total sample = 1,966 adults. Fieldwork was conducted online between 26–27 February 2013. Figures have been weighted and are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

Figure 1 indicates there is little public support for actions such as assassinating Bashar al-Assad or scientists working on Iran’s nuclear programme. But a majority of the British public supports the policy, at least in principle, of assassinating known terrorists and pirates/hostage-takers.

Support is strongest in these results for the targeted killing of pirates/hostage-takers, with 57% of respondents overall saying they would support the UK government taking part or assisting in this kind of targeted killing, versus 29% saying they would oppose.

Support for assassinating known terrorists is weaker by comparison, but still constitutes an overall majority: 52% overall say they would support the UK government taking part or assisting in the assassination of terrorists in the UK, versus 34% saying they would oppose, while 54% overall say they would support similar action against known terrorists overseas, versus 31% saying oppose.

Behind national totals, Lib Dem voters stand out next to supporters of the other large parties, with less support for the policy of targeted killing against known terrorists, both in the UK and overseas. A majority of current Conservative and Labour voters said they would support the UK government taking part or assisting in the assassination of known terrorists in the UK (respectively: Cons – 63% support vs 27% oppose; Lab – 52% support vs 38% oppose), while in contrast, a 51% majority of current Lib Dem voters said they would oppose the same action, with 40% saying they would support.

Similarly, a majority of current Conservative and Labour voters said they would support the UK government taking part or assisting in the assassination of known terrorists overseas (respectively: Cons – 61% support vs 29% oppose; Lab – 55% support vs 33% oppose), while a small 53% majority of current Lib Dem voters said would oppose the same activity, with 37% saying they would support.

Attitudes to the Overall Impact of Drone Strikes on Western Security

The British public is divided, it seems, on the broad question of whether drone missile strikes in countries like Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia are ultimately helping or hindering Western security:

- 32% of all respondents say: ‘On balance, drone missile strikes have made the West more safe overall by making it easier to target known terrorists’

- 31% of all respondents say: ‘On balance, drone missile strikes have made the West less safe overall by turning public opinion against us in countries where they are used’

- 37% of all respondents selected ‘neither of these’/‘don’t know’.

Results further indicate a notable divide between conservative and liberal sections of the electorate.

- A plurality of Conservatives (46%) believe drone missile strikes have ultimately made the West ‘more safe’, compared with 26% saying ‘less safe’ and 27% who selected either ‘don’t’ know’ or ‘neither of these’

- By comparison, a plurality of Lib Dems (41%) say the opposite – that these strikes have ultimately made the West ‘less safe’, compared with 32% choosing ‘more safe’ and 26% who selected ‘don’t know’ or ‘neither of these’

- Attitudes among Labour supporters follow a similar direction of opinion to Lib Dems, but are more evenly spread among those who answered ‘more safe’ (29%), less safe (36%) and either ‘don’t know’ or ‘neither of these’ (34%).

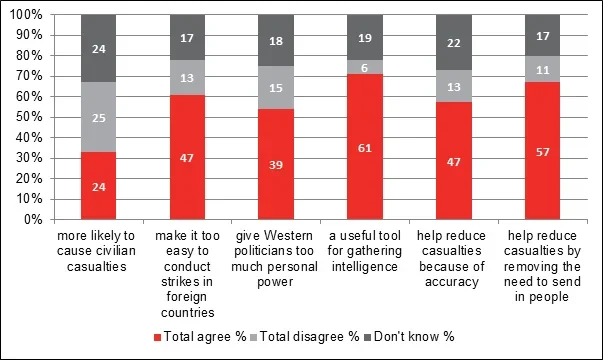

Attitudes to Pro/Con Arguments about Drones

This is not to suggest there is no consensus in British attitudes to drones. People were also asked to what extent they agree or disagree with three pro-drone arguments and three con-drone arguments that have helped to characterise recent public debate on the subject.

These arguments included:

- ‘Drones help to reduce casualties by removing the need to send in people on the ground’

- ‘Drones help to reduce casualties because of their accuracy compared with other weapons used over long distances’

- ‘Drones are a useful tool for gathering intelligence’

- ‘Drones give Western politicians too much personal power to pick and choose who is killed’

- ‘Drones make it too easy for Western governments to conduct military strikes in foreign countries’

- ‘Drones are more likely to cause civilian casualties than other weapons used over long distances’.

Figure 2: ‘Thinking about drone missile strikes, to what extent, if at all, do you agree or disagree with the following statements?’

Total sample = 1,966 adults. Fieldwork was conducted online between 26–27 February 2013. Figures have been weighted and are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

Responses to ‘Pro-Drone’ Arguments:

A 57% majority agreed overall that drones help to reduce casualties ‘by removing the need to send in people on the ground’. This included majorities among supporters of all three major parties. (Respectively: Cons – 68% agree vs 8% disagree; Lab – 57% agree vs 14% disagree; Lib Dems – 60% agree vs 15% disagree.)

A significant plurality (47%) also agreed that drones help to reduce casualties ‘because of their accuracy compared with other weapons’. This included a majority of current Conservative voters and a plurality of current Labour voters, while a plurality of Lib Dems disagreed. (Respectively: Cons – 57% agree vs 8% disagree; Lab – 49% agree vs 16% disagree; Lib Dems – 36% agree vs 18% disagree.)

A clear majority further agreed that drones are useful for intelligence, including similar majorities among supporters of the major parties. (Respectively: Cons – 70% agree versus 5% disagree; Lab – 62% agree versus 6% disagree; Lib Dems – 65% agree versus 9% disagree.)

Responses to ‘Contra-Drone’ Arguments:

In the same results, however, a significant plurality agreed that ‘drones make it too easy for Western governments to conduct military strikes in foreign countries’, with 47% of respondents overall saying they agreed. This included majorities or pluralities of Conservative, Labour and Lib Dem supporters saying the same. (Respectively: Cons – 46% agree vs 20% disagree; Lab – 51% agree vs 12% disagree; Lib Dems – 58% agree vs 12% disagree.)

The electorate is more politically divided on the question of individual accountability among policy-makers. Just 39% of respondents overall agreed with the statement ‘drones give Western politicians too much personal power to pick and choose who is killed’, while 15% disagreed, 28% said ‘neither agree nor disagree’ and 18% selected ‘don’t know’. A majority of Lib Dems agreed, along with a smaller plurality of current Labour voters, while Conservative responses essentially mirrored the national totals. (Respectively: Cons – 37% agree vs 23% disagree; Lab – 43% agree vs 14% disagree; Lib Dems – 52% agree vs 12% disagree.)

Finally, a wide spread of answers was produced with no strong trend in responses to the statement: ‘Drones are more likely to cause civilian casualties than other weapons used over long distances’. 24% of respondents overall agreed, alongside 26% who chose ‘neither agree nor disagree’, 25% who said ‘disagree’ and 24% who selected ‘don’t know’. Responses among party camps showed a similar divergent spread of percentages.

In summary, these figures suggest an important fault-line in public opinion towards drones. The British public may be divided overall on whether current drone deployments are doing more harm than good to Western security. But there is also a distinction between attitudes to the effect of policy and the potential merits of drones themselves.

Among the first category of attitudes, a third of Britons believe the current use of drones is undermining Western security by turning public opinion against those associated with the strikes, while substantial pluralities among more liberal voters believe it gives politicians too much power to ‘pick and kill’. Nearly half of the electorate also say drones are making it too easy for Western governments to take military action on foreign soil.

But in the second category, a cross-party majority agree that drones help to reduce casualties by removing the need for boots on the ground, and a plurality including nearly 60% of Conservatives and almost half of Labour supporters agree they help to reduce casualties through their comparative accuracy. A majority also support the policy in principle of targeting killings against known terrorists, albeit with a small majority of opposition from Lib Dems.

Notes on Methodology

Survey 1 was undertaken between 27–28 February 2013. Total sample size was 1,761 British adults. The survey was carried out online. The overall sample was split into two sub-samples of n=883 and n=878. Full results can be found here.

Survey 2 was undertaken between 3–4 March 2013. Total sample size was 1,727 British adults. The survey was carried out online. The overall sample was split into two sub-samples of n=871 and n=856. Full results can be found here.

Survey 3 was undertaken between 4–5 March 2013. Total sample size was 1,906 British adults. The survey was carried out online. The overall sample was split into two sub-samples of n=933 and n=973. Full results can be found here.

Survey 4 was undertaken between 6–7 March 2013. Total sample size was 1,865 British adults. The survey was carried out online. The overall sample was split into two sub-samples of n=953 and n=912. Full results can be found here.

Survey 5 was undertaken between 7–8 March 2013. Total sample size was 1,525 British adults. The survey was carried out online. The overall sample was split into two sub-samples of n=802 and n=723. Full results can be found here.

Survey 6 was undertaken between 26–27 February 2013. Total sample size was 1,966 British adults. The survey was carried out online. Figures have been weighted and are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over. Full results can be found here.