Most mothers across 17 countries and regions say they can – except in Britain

In 2012 public policy expert Anne-Marie Slaughter made waves when she wrote an article in The Atlantic entitled “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All”.

In it, Slaughter described her own struggle with “having it all”: juggling her high level government work with the needs of her two teenage sons, followed by the reactions from other women when she decided to change jobs so she could spend more time with her family.

While she does believe that it is possible for women (and men) to “have it all”, Slaughter argues that American society is not structured to allow them to do so, and that too many women have been led to believe that they were at fault if they struggled with the pressures of career and family demands.

Now for International Women’s Day 2020, YouGov has asked people in 17 countries and regions whether or not they believe it is possible for anyone to “have it all”, and if so, for who?

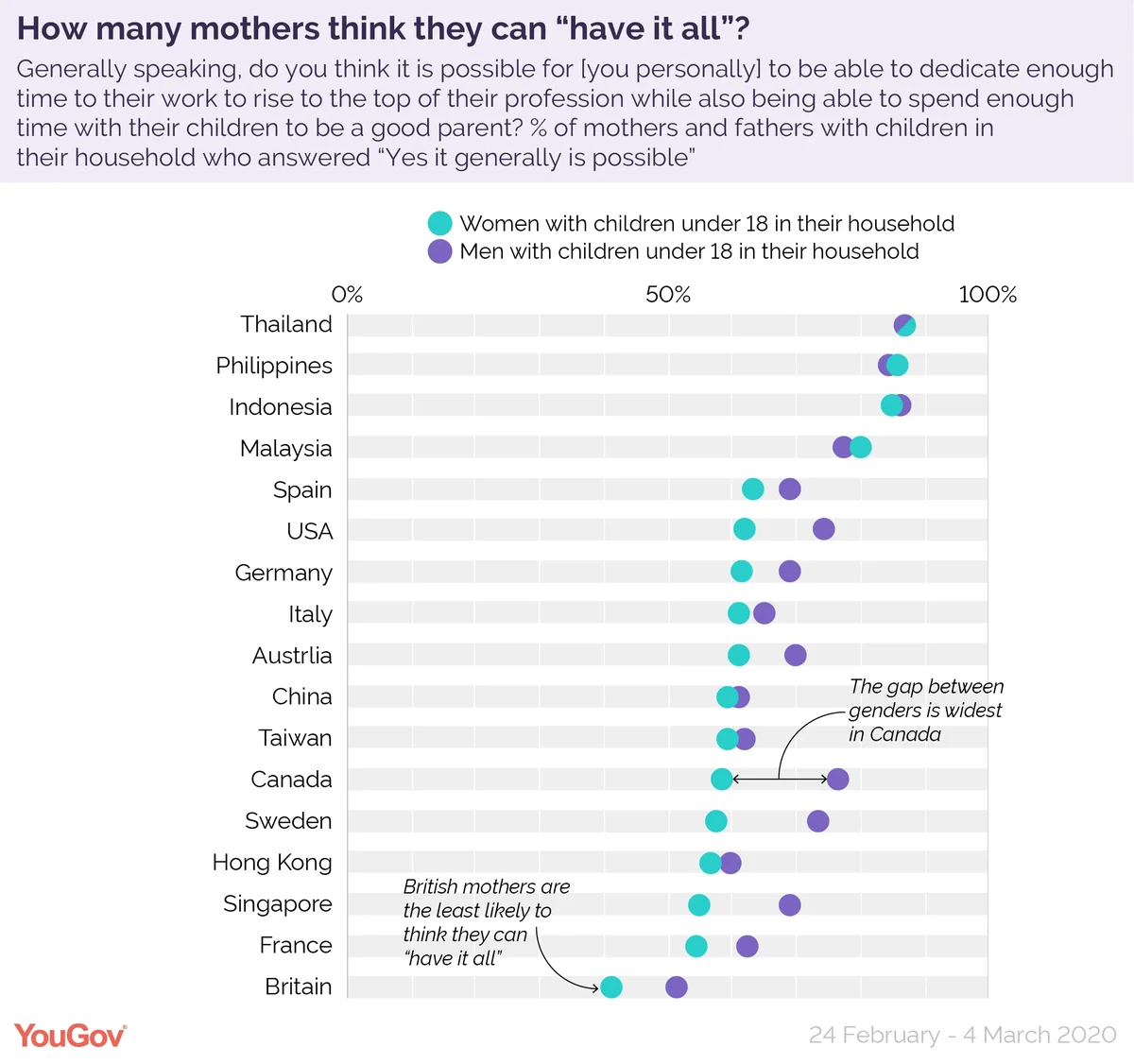

Mothers in Western countries tend to be less likely than fathers to think they can have it all

We asked women (and men) with children under the age of 18 in their household whether or not they thought it was possible for them personally to be able to dedicate enough time to work to rise to the top of their profession while also spending enough time with their children to be a good parent (our proxy for “having it all”).

British women with children in their household are the least likely to think they are able to do so, with just 41% saying they generally think they can have it all. This compares against 51% among British fathers with kids at home. While this is a noticeable difference, it is worth noting that British fathers scored lower than any other group (both fathers and mothers) from any other country.

When looking at the gender gap in other countries, the biggest is in Canada. Three quarters (76%) of Canadian fathers think they can generally have it all, compared to 58% of mothers – a gap of 18 percentage points. Another country with a big gap between fathers and mothers is Sweden: 16 points between the two (73% versus 57%). In Singapore there’s a 14 point gap (69% for fathers, and 54% for mothers).

On the other end, the gap is narrowest in Thailand. This is also the country where mothers and fathers are most likely to believe they themselves can have it all. As many as 87% of Thai mothers (with their children living in their household) believe they can excel in both their career and as a parent, a figure which is identical among Thai fathers.

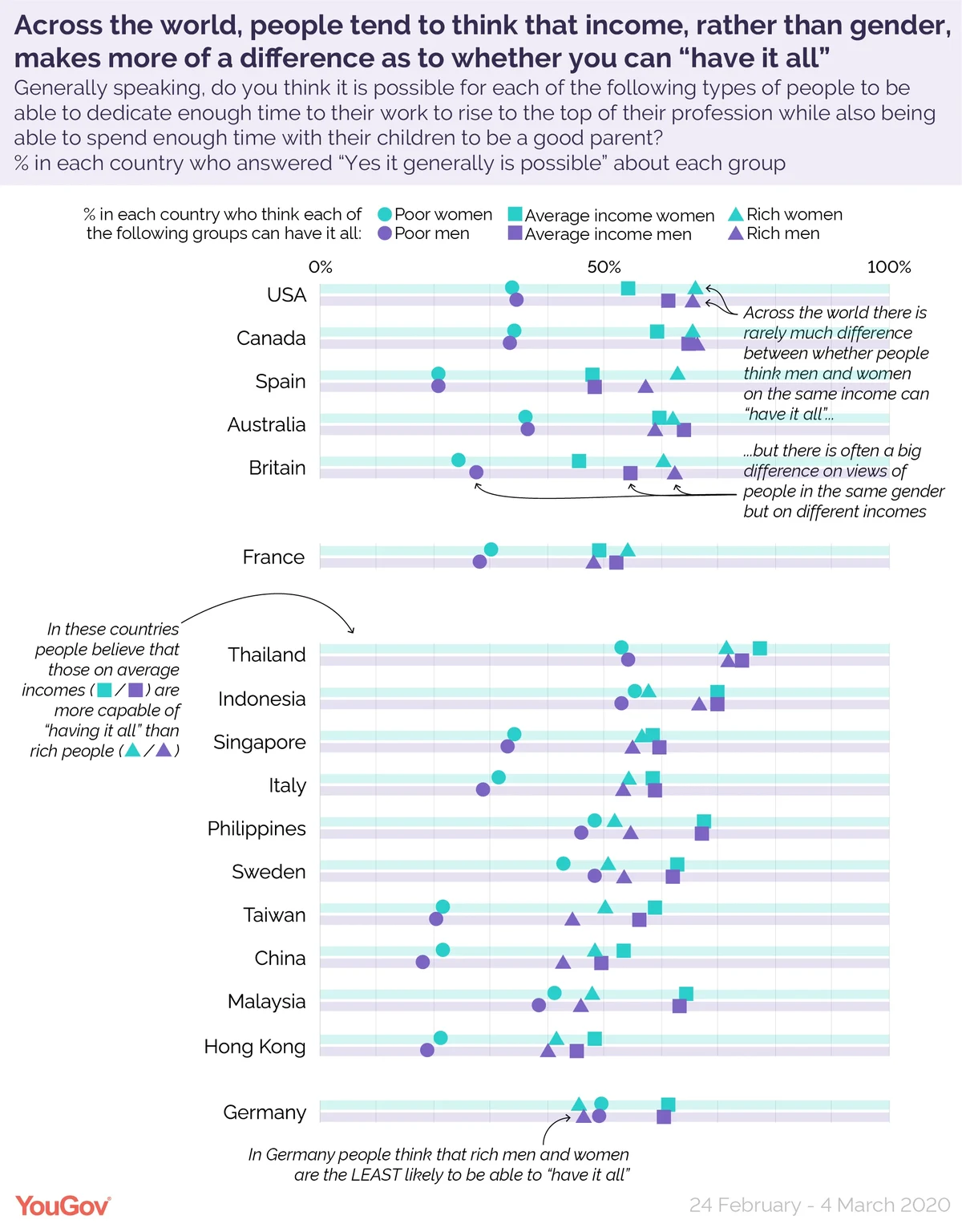

People think income matters more than gender when it comes to having it all, but the dynamic plays out differently around the world

The study also looked more broadly at social expectations of what kind of people can “have it all”.

Anne-Marie Slaughter suggested in her article that only rich women could really have it all. The results agree: income plays a bigger role than gender in whether people think someone can have it all. In the vast majority of cases, people tend to think that men and women of the same income level are about as likely to be able to have it all.

For instance, here in Britain 62% of people think a rich man can generally have it all, a mere two percentage points different from the 60% who think a rich woman can do so. However, when it comes to whether poor mothers and fathers, just 24-27% of Britons say the same – a gap of more than thirty percentage points separating expectations of rich and poor.

However, this income dynamic plays out differently elsewhere in the world. In the USA, Canada, Spain, Australia and Britain, the wealthier a person was described as being, the more likely it was that people would say that they could have it all.

Yet in the other countries studied, people are actually more likely to think that people on average incomes were more capable of having it all than rich people. For instance, in Sweden while 61-62% of people believe mothers and fathers on average incomes can “have it all”, this figure falls to 50-53% when asked about rich parents.

In fact, in Germany, the rich are the group that Germans are least likely to see as being able to have it all. The impact of income on this opinion is also lowest in Germany: the range of people agreeing that people can have it all goes from a low of 45% to a high of 61%. By contrast, in Britain the range is wider, going from 24% at its lowest to 62% at its highest.

This could be a result of cultural differences. In some countries, it may be the belief that in order to be rich a person must inherently have to work such long hours that they are unable to make time for family. It does also raise the prospect that people in different countries are interpreting the “rise to the top of their profession” element of the question differently. Success in professions and across countries may not all look the same.

Differences in how women and men responded to the questions also varied from country to country, but big differences were the exception rather than the norm.

The biggest difference is in Indonesia, where 77% of female respondents believe a woman on an average income can ‘have it all’ compared to 63% of male respondents. Indonesian women were also noticeably more likely than Indonesian men to think that rich women, poor women and average income men could generally dedicate enough time to both their career and their parenting.

Here in Britain, male respondents are somewhat more confident than female respondents that a woman on an average income (49% versus 42%) or a poor woman (28% versus 20%) can “have it all”.

Photo: Getty