History helps to explain why Britons favour European equality over American individualism.

The Long Slump is supposedly widening the English Channel. This is doubtless the case politically. Tough economic times have hardened British public opinion towards core elements of the European Project, from porous borders and economic interdependence to supranational policy, and in ways that are broadening the ranks of smaller parties and the schisms of big ones. In the process, Britain is heading, near inevitably it seems, towards some form of renegotiated European detachment with a slug of public support.

In other ways, however, capitalism’s latest crisis is serving to highlight a fundamental European leaning in the British mind-set, and to revise certain assumptions that emerged in the gap between Soviet and Lehman collapse about the depth of 'Thatcherisation' and 'Atlanticism' in Britain.

Lest we forget, this was a period when even left-wing gurus declared we were ‘all Thatcherites now’. And so it appeared – to an extent.

At home, the Young Turks of the New Left force-drafted a facsimile of Thatchernomics that was just about palatable to a wider Labour Party that seemed just about ready to try anything to get back into power.

Meanwhile, international financial agencies like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund sought to embed a 10-point version of the Thatcher-Reagan model for marketisation into emerging and de-Communising economies through conditional lending and structural adjustment programmes.

As Margaret Thatcher divided a nation in this period, so she polarised debate at the latest YouGov-Cambridge Conference – perhaps more noticeably as it coincided with the day of her funeral.

Held in partnership with Cambridge University and the Guardian, the programme was originally designed to look at public trust in banking five years on from the Crash, supported by a special YouGov report on the subject.

But in the week before the conference, we fast updated the programme to incorporate the renewed debate on Thatcherism and its continuing impact.

Nb: this included some exciting highlights worth a look, such as Sir Philip Hampton, Chairman of The Royal Bank of Scotland Group, challenging the popular view that British banks are maliciously withholding capital from the economy (more here); Observer Columnist Will Hutton clashing with Allister Heath, Editor of City AM, on the balance of market forces and government intervention in the causes of the crisis and strategies for recovery (more here); and Fraser Nelson, Baroness Falkner and Jonathan Freedland et al on whether the end of Thatcher’s premiership marked the start of a “post-ideological age” (more here).

The Atlantic fault-line in Western attitudes to the state

Beyond the familiar, tribal dissensus, however, both speakers and a trove of supporting conference research helped to clarify a broader, important nuance in Thatcher's legacy, which is coming into sharper relief as the slump endures.

On one hand, the Thatcher period clearly marked a British turning point in the general acceptance of certain free market virtues.

According to research conducted in the run-up to the YouGov-Cambridge Conference, for example, Britons take a broadly Thatcherite view in their attitude towards successful and failing companies. 52% of Britons say “companies and industries that are not competitive or profitable should be allowed to close, even if this means that the people working in them lose their jobs”, versus 27% who chose the option, “Companies and industries that are not competitive or profitable should receive subsidies from the government to keep them open and protect the jobs of those working in them, even if this means higher taxes”.

Profits are usually the sign of a well-run company, according to 52% of Britons, versus 32% who say it is usually a sign that the company is exploiting workers and/or customers.

A plurality of Britons also endorse a more Thatcherite view of unions: 45% say a stronger and more influential Trade Union movement would be a bad thing for Britain, versus 34% saying the opposite.

These attitudes have stood the test of twenty years and now a severe, global crisis caused (arguably) by unrestrained capitalism.

However, if the Thatcher period hailed an enduring acceptance of certain market laws, it did less to shift deep-seated attitudes towards the scope of the government's role in national life. As the Guardian noted in coverage of the conference and its research, Thatcher may have taught Britain to love business, but not to hate government.

Figures from the same survey show, for instance, that a strong 61% majority believe most major public utilities, such as energy and water, are best run by the public sector, as accountable to the government and Parliament, versus only 26% saying they are best run by private companies, as accountable to shareholders and regulators and competing for customers.

Long-running studies such as the British Social Attitudes Survey have suggested a longer-term hardening of attitudes in Britain towards the question of redistribution, for example with the proportion of the Britons who agree that ‘government should spend more on welfare benefits even if it leads to higher taxes’ falling from 58% in 1991 to 28% in its 2012 edition.

However, as a separate, international survey for the same YouGov-Cambridge conference also suggests, there remains an Atlantic fault-line in Western attitudes to government that leaves Britain notably closer to Europe than the United States in basic attitudes to equality, welfare, and the responsibilities of state versus individual.

Follow @YouGovCam for updates on our academic research

As a key influence in Thactherism, the Viennese intellectual Friedrich von Hayek once proposed what he called “true individualism”, which distinguished between two definitions of equalitarianism: one that tries to make people more equal through intervention, and another that seeks to ensure equal freedom to compete, which crucially denies government the right to limit what people might be fortunate to achieve.

Thatcherism canvassed tirelessly for the latter. But there's a deep historical difference in evolution between British and American polities, which helps to account for why the harder-edged principles of Hayekian individualism are more at home in the United States than in Britain.

The American relationship of geography to individualism

From the earliest settlements, and especially from the formative era of the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth centuries, the founders of American nationhood saw themselves as exceptional not only because of their political revolution, but quite fairly on account of the very environment that became their home – a vast and rapidly discovered continent.

It was consequently a Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, who first established the study of “American Exceptionalism” when he arrived in the United States during the 1830s hoping to understand how the American Revolution had succeeded where its French counterpart had failed. As de Tocqueville concluded, this new nation was exceptional not only in its institutions, but also – and perhaps more importantly – in its sheer abundance of space, where “God himself” had given Americans the means of remaining equal and free by placing them upon a boundless continent.

Consequently, on a crowded European landmass that has abhorred a vacuum of power and ownership since at least Charlemagne, European political philosophy has often conceived of change in the balance of wealth as requiring expropriation here and corresponding aggrandisement there.

In contrast, as colonists and migrants flooded into an allegedly open and initially expanding land of opportunity, the thrust of American political thought came to see changes in this balance as reflecting an individual’s ability to gain without necessarily taking from others.

So whereas European equalitarianism has traditionally focused on the right of people to exist on similar levels, founding American notions of equality came to focus more on people’s newfound freedom to do so on levels different from others.

In this way, notions of equalitarianism evolved between the 19th and 20th Centuries with varying emphasis across the Atlantic – in America more on protecting the freedom of competition; in Europe more on aspiring to greater parity of circumstances.

This is not to fudge the particularisms of British political thought in this period – there is a very independent stream of British socialism that derives from a 19th century background of Christian as well as radical heritage.

But as the Guardian further noted in its conference coverage here and here, Britain remains broadly in line with continental Europe in accepting a basic responsibility of state to provide universal safety nets, to redistribute income and to cap the biggest pay cheques.

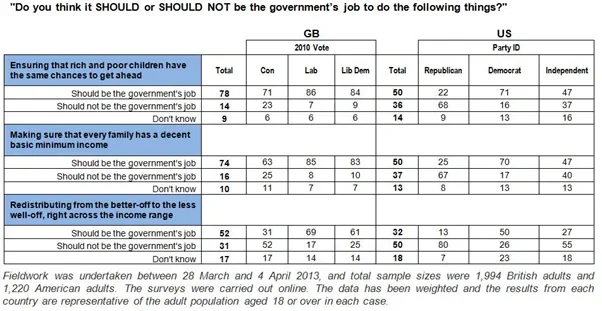

According to cross-country research conducted in Britain, France, Germany and the United States, 52% of Britons say the government’s job should include “redistributing from the better-off to the less well-off, right across the income range”, compared with 31% who say it should not.

Opinion-trends are similar in France and Germany: 62% of French say it should be the government’s job versus 24% saying it shouldn’t; 54% of Germans say it should versus 31% saying it shouldn't.

Trends in the United States meanwhile are reversed: 50% say it should NOT be the government’s job versus only 32% saying it should.

In much the same fashion, 78% of Britons believe the duty of state includes making sure that rich and poor children have the same chances to get ahead, versus 14% saying it shouldn't. The French and German publics show comparable margins: 77% and 87% respectively say it should be versus 17% and 8% saying it shouldn’t.

A majority of Americans support the proposition, but only just: 50% say it should versus 36% saying the opposite.

Similarly again, 74% of Britons and French, along with 76% of Germans believe the government should ensure every family has a decent basic minimum income, versus 16%, 18% and 16% respectively who say the opposite. The margins in America are also similar again, with 50% saying it should and 37% saying it shouldn’t.

The British and American Right compared

British and American conservatives in this context make for some notable contrasts, as Table 1 shows.

Results suggest that many British conservatives still support certain sweeping responsibilities of state where American conservatives strongly reject them.

63% of current Tory voters, for example, believe that making sure every family has a decent basic minimum income should be part of the government’s job, versus 25% who say the opposite.

Compare this with US conservatives, where only 25% say it should be the government’s job, versus 67% who say it shouldn’t.

Similarly, where 60% of current Tory voters say the government’s job should include ensuring that rich and poor children have the same chances to get ahead, only 22% of US Republicans say the same.

In a separate question we asked to what extent respondents would support an increase in the funding of government programs for helping the poor and unemployed, even if this might raise taxes. 46% of British conservatives still supported the proposition, versus 27% who opposed. Among US conservatives, only 24% chose support versus 59% who opposed. (see the full British results and full US results)

Britain is mid-Atlantic on the pay gap

The same study also tested attitudes to the pay gap between high and low salaries, and whether people at the top of the pay scale should be free to earn limitless multiples of those at the bottom.

Respondents were asked whether it was acceptable for someone in their country on a top wage, such as people running a large company or organisation, to earn 20 times more than a low-wage worker. In each country, we expressed the figures in local currencies, so people in Britain were asked if they thought it was acceptable for a high earner to earn £300,000 per year if someone on a low wage is earning £15,000 per year. In the United States the figures were $400,000/$20,000, while in France and Germany they were €400,000/€20,000.

Large majorities in continental Europe said €400,000 was unacceptable – 65% in France and 62% in Germany, versus 26% and 28% respectively saying either this was acceptable or that successful bosses should be allowed to earn still more. In contrast over the Atlantic, 53% of Americans said it was acceptable or that people ‘should be allowed to earn more’, versus 31% saying it was unacceptable. Meanwhile, the British public sits broadly divided and ‘mid-Atlantic’, with 47% saying it was unacceptable versus 42% saying acceptable.

In other words, Britain doesn’t share the same European opposition to supersized and unlimited salaries. But neither does it reflect American support for them.

More in common with the United States?

In a final question added to the British survey, we asked if people thought that Britain ultimately had more in common with the people of the United or Europe.

Interestingly, a plurality of 44% chose the United States versus a smaller 35% who chose Europe.

So it might surprise some to know that Britain still favours European equality over American individualism.

Follow @YouGovCam for updates on our on-going academic research

See the full cross-country results

See the full survey results for our final Thatcher poll