As part of today's YouGov-Cambridge conference, a special report reveals that people around the world choose practical solutions over the ideological struggles of the 20th Century

For almost two decades – from the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 to the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 – the great ideological struggles of the 20th Century seemed to be over. Capitalism won. Governments were thought to be hopeless at running the main enterprises of modern economies and market forces were deemed to hold the key to prosperity.

See the full YouGov CambridgeProgramme report: Public Opinion and the Evolving State

Since 2008, confidence in the infallibility of markets has been shattered. The banking crises and recession that afflicted the United States and much of Europe have been the immediate cause; but there have been other signs of trouble, from the collapse of Enron in the United States to the growing gulf between rich and poor in most market economies. A new anxiety has revived an old question: what is the proper balance between public and private ownership – and what role should competition and government regulation play?

What do the people – the workers and consumers – think? The YouGov-Cambridge research reported here has measured public attitudes to ownership and competition in Europe, the United States, China and the Arab and Islamic worlds.

The role of government

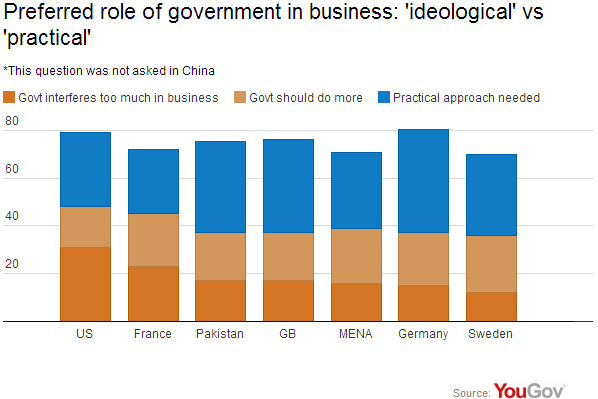

In broad terms,around 40% in each of the countries we surveyed hold an ‘ideological’ view – either that Government interferes too much or should give private companies less freedom to take their own decisions. In each country, the largest group want either to keep the present level of regulation or a pragmatic case-by-case approach to regulation. (This was the one question we did NOT pose in China.)

Support for the laissez-faire option is highest in the United States (US) and lowest in Sweden; but even in the US, it has the backing of just 31%. An equal number favour a case-by-case approach. Support for pragmatism is especially strong in Germany (43%) and Britain (39%.). Support for a greater government role is more even across the countries we surveyed – around 20% in each case.

Nationalisation

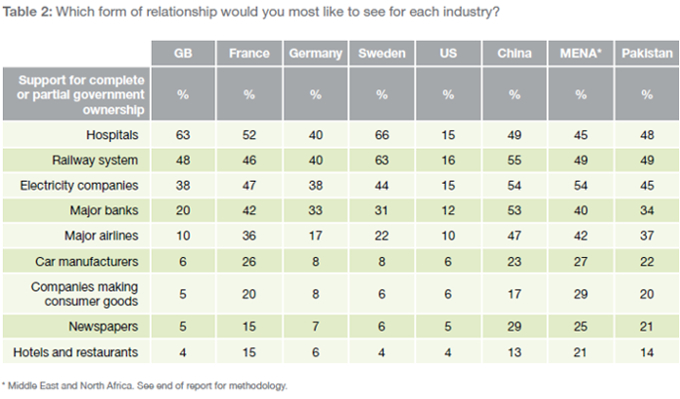

How, though, do people want each industry to be owned and regulated?

Table 2 shows the level of support for partial or complete government ownership. Not surprisingly, the United States stands out as the country that likes it least. This reflects not only the different nature of its internal political debate – “socialism” has been a dirty word for many decades – but the lack of past experience of government ownership in the sectors covered by our survey. In Europe, privatisation has been widespread, but we do not need to delve too far back into our history to find the days when our railways, airlines and energy companies were state-owned.

As for sectors that have traditionally been the preserve of private companies, the appetite for nationalisation has all but disappeared in Britain, Germany and Sweden. On the other hand, a significant minority of French people still subscribe to the religion of state socialism for the supply of goods and services.

This is also true of the Islamic world, with its more complex relationship between capitalism, especially banking, and the Koran.

Perhaps the most striking results concern China. In a country that describes itself as Communist but which practices its own brand of capitalism, the division in attitudes is very similar to that across Europe, with around half the public wanting hospitals, banks and energy and transport companies in partial or complete government ownership, but only a minority wanting companies providing consumer goods and services in the hands of the state.

Regulation

However, where Chinese people do not want state ownership, they DO want strong regulation rather than private owners left to make their own decisions, subject only to light regulation and the laws of the land. Only 11% of Chinese respondents want car manufacturers that are largely free of government regulation. The figures are slightly higher for companies making consumer goods (13%), newspapers (14%) and hotels and restaurants (16%), but they are still generally far lower than those in Europe or the United States.

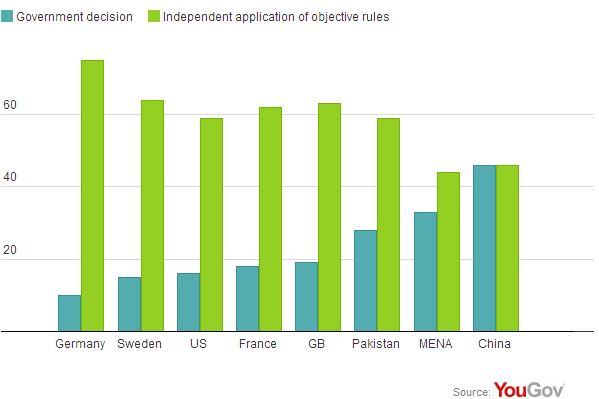

China’s continuing appetite for state regulation shows up in answers to another question about how decisions should be taken when the public interest is invoked. We asked:

In general, when specific actions are taken by, or on behalf of, the government in relation to different industries (for example whether to approve a merger, or major investment, or planning proposal), how should the main decisions be taken?

Across Europe and the United States, and also Pakistan, most people want the independent application of objective rules. But in China, attitudes are evenly divided. Perhaps if either the Government or a system of independent decision could demonstrate a capacity for honesty and efficiency, it would command clear majority support.

Competition

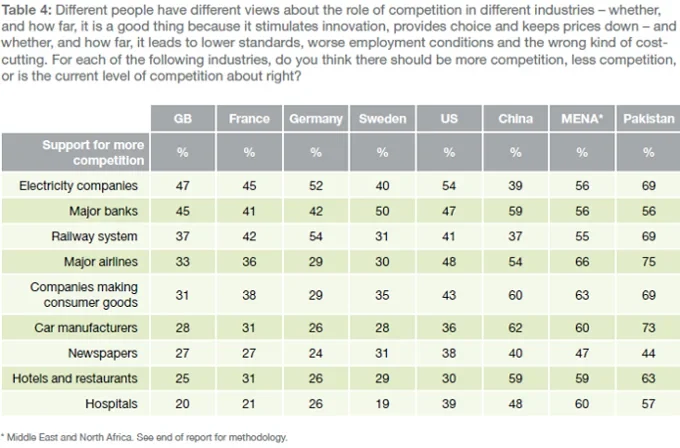

Finally, we explored attitudes to competition. As we have discovered in recent decades, privatisation does not always banish monopolies or produce fully competitive markets. And, in theory at least, it is possible for rival enterprises to be state-owned and still fiercely competitive. So we repeated our list of industries and asked:Different people have different views about the role of competition in different industries – whether, and how far, it is a good thing because it stimulates innovation, provides choice and keeps prices down – and whether, and how far, it leads to lower standards, worse employment conditions and the wrong kind of cost-cutting. For each of the following industries, do you think there should be more competition, less competition, or is the current level of competition about right?

Overall, the results of our survey suggest that the advocates of the market system have won the basic argument: most people in all the countries we surveyed want large doses of competition across most sectors of the economy – hospitals in Europe being the one exception among the nine sectors we tested. However, it is clear that there are also widespread concerns about the way governments and private companies behave. For many people in many countries, the ideal is a more competitive economy, with a variety of forms of ownership and smarter, but not more onerous, forms of independent regulation.

These are concepts that resist simple slogans or clear-cut ideologies. Most people nowadays reject the grand theories and great Left-Right struggles of the last century. Rather, we want practical solutions to complex problems – honesty and competence more than anger and vision. Maybe it is time to reach back to William Blake’s words from two centuries ago: “He who would do good to another must do it in minute particulars: general good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite and flatterer.”

Image: Getty