YouGov's Chris Curtis looks at the obstacles facing the Independent Group

This article originally appeared in the Metro

The newly formed Independent Group, created by defecting Labour MPs, will be hoping to siphon off more disaffected politicians in coming days and weeks and build a fresh centrist force in British politics.

And there are many reasons to believe that there’s fertile ground for such a new party. For starters, the two main parties collectively polled 82.4% of the vote in the most recent election, a level that feels unsustainably high by modern standards. You have to go all the way back to 1970 to find an election where they were more dominant.

The rising unpopularity of their leaders makes this two-party politics seem even less sustainable. Our recent polling shows that just 30% of the public has a favourable view of Theresa May, and 58% have a negative opinion. And the public’s view of Jeremy Corbyn is even worse, with scores of 22% and 67% respectively.

Furthermore, with Brexit dominating the political agenda, the main two parties have been finding it increasingly tricky to hold their coalitions of voters together. There are nearly 4,000,000 Britons who voted Remain and then supported the Conservatives in the last general election, and many of those will feel increasingly unwelcome in a Conservative party edging towards hard Brexit.

On the other side, there seems to be increasing frustration amongst Labour voters caused by the leadership not taking a stronger stance against Brexit. The majority (56%) of those who backed Labour at the last election now think that a second EU Referendum, followed by Britain staying in the EU, would be a good outcome for Britain.

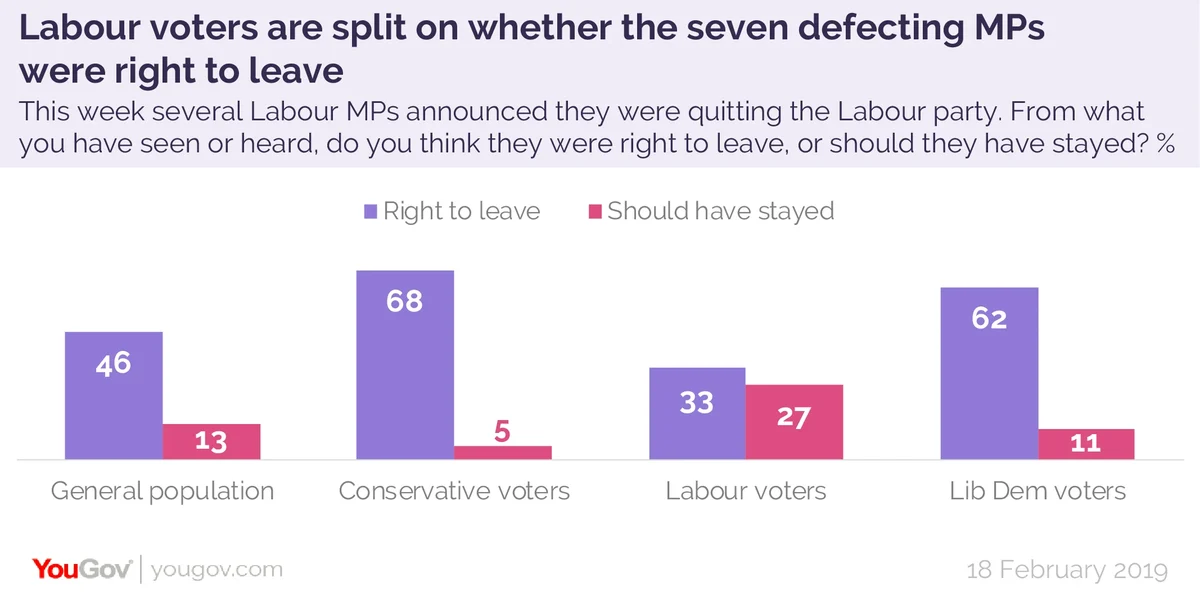

So it is perhaps no surprise that our recent polling for Hope Not Hate shows that 68% of the public feel that none of the parties currently speak for them, and our snap polling reveals that 46% think these Labour MPs were right to splinter away and form a new group, compared to just 13% who think they should have stayed.

But while voters may be open to the idea of a new centrist party in principle, there are still many structural difficulties the new gang of seven will face in actually gaining the public’s votes.

The first is leadership. Back in 1983 the SDP split was led by some of the most well-known politicians in the country, whereas most of the politicians who left the Labour party yesterday are almost unheard of. For example, YouGov ratings data shows that just 19% of the public have heard of Luciana Berger before she launched yesterday’s press conference. Whilst Chuka Umunna is slightly better known, with the majority (52%) of the public recognising him, just 15% currently have a positive opinion of him.

The second obstacle will be filling a manifesto with policies that extend beyond Brexit. Whilst there may be votes to capture by coming out against Brexit, or at least in favour of a second referendum, it isn’t clear how the party could position itself beyond that.

One problem they will face is that many voters who share their position on Brexit are also close to Corbyn on economic policy. For example, 67% of Remain voters think the railways should be run by the public sector, 65% feel the same way about water companies and 55% about the energy sector. Nationalisation of all of these is already a keystone of Corbyn’s manifesto.

Even if they can overcome the leadership and policy hurdles, they’ll still have to contend with an electoral system that favours the bigger parties. Modern British history is littered with new political parties who managed a good showing at the ballot box only to find that “first past the post” system doesn’t necessarily translate their votes into seats.

From the 1983 election, where the SDP alliance got over a quarter of the vote but less than 4% of the seats, to 2015 when UKIP got 12.6% of the vote share but didn’t gain the most votes in a single constituency. It is difficult to see how this new party won’t be plagued with these difficulties as well.

There’s certainly fertile ground for a new political party, and the Independent Group has firmly planted itself in the British political landscape, but only time will tell if it can grow.

Photo: Getty