Enough numbers of Leave voters are wavering in their support for the Conservative party to put Labour ahead in the polls

In the weeks running up to the Chequers summit the Conservatives appeared to be opening up a consistent lead in the polls. In the ten polls before the big meeting they held an average lead of 3.5 percentage points.

However in our first poll after the events of last weekend the Labour party had taken a lead for the first time since early March, on 39% to the Conservatives' 37%. In the aftermath of the Boris Johnson and David Davis’s resignations, it appears to be Conservative Leave voters who are moving away from Theresa May’s Conservative party.

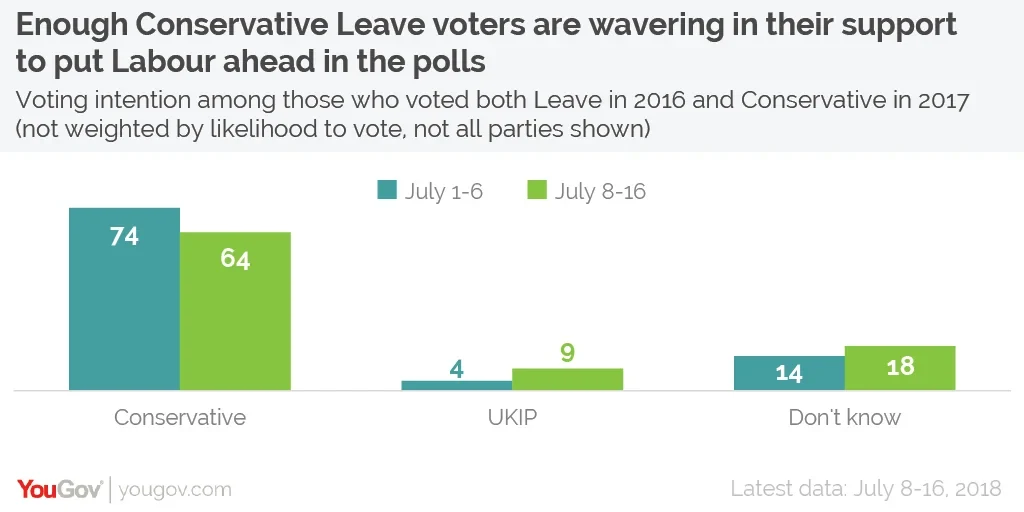

In the week before and after the deal we surveyed more than 1,500 people who voted Leave at the EU referendum and then Conservative in the 2017 general election. In the week before the deal three quarters (74%) said they planned to stick with the Conservative party, with just 5% saying they would vote UKIP, 5% saying they would vote for another party, and 14% saying they didn’t know how they would vote. (These numbers haven’t been adjusted for likelihood to vote)

In the week following Chequers the number saying they would stick with the Conservative party has dropped by ten percentages, with just 64% saying they would now vote for them in a general election. This was contrasted by an increase in the number saying they would now vote UKIP, from 4% to 9%, and the number saying they don’t know how they would vote rising from 14% to 18%.

These numbers might seem quite small, but the Leave vote is now such a large part of the Conservative coalition that it could severely damage their electoral chances. Of those Conservative voters in the last election that had voted in the referendum, just three in ten (29%) backed Remain compared to seven in ten (71%) who backed Leave. And with the two main parties so close in the polls, this has been enough to turn a small Conservative lead into a small Labour lead.

The question then becomes how firm this move in opinion is, and what these voters might actually do when push comes to shove.

Firstly, losing voters to “don’t know” makes them a lot easier to win back in a general election campaign than losing them to another party - particularly if they don’t think there is anywhere else they can go. For example, YouGov polling during the 2017 general election showed that, even before the “Corbyn surge”, ex-Labour voters who previously told us they didn’t know how they started switching back to Labour once the election was called.

When it comes to the voters the Tories are losing to UKIP, the latter party is unlikely to have the organisation in place to turn this sentiment into actual votes in an election. Over four in ten (43%) of those who currently say they would UKIP in a general election live in constituencies where the party didn’t field a candidate at the last election.

UKIP leader Gerard Batten has also been struggling to cut through with the public, and a poll in early June showed that over seven in ten Britons (71%) felt they didn’t know enough about him to form an opinion.

So while this loss of support is obviously not desirable for the Conservatives it is still too early to know if this particular shift would actually harm them on a hypothetical election day itself. As things currently stand there is no party in this space that is organised enough to guarantee that these voters would actually defect.

But if UKIP does kick their party machinery up a gear enough to turn this sentiment into votes, or even if a new alternative party takes its place, it could spell trouble for the Conservatives at the next election.

Photo: Getty

See the full results for pre-Chequers data here and post-Chequers data here