Much will be made of the popularity of parties’ manifesto pledges, but ultimately they are much less important to how people vote than other factors like leadership and core values

This article originally appeared on the New Statesman website

In every election, some political figure will either say that their party will start to gain popularity when the public sees its manifesto, or that people should vote based on “policies, not personalities”. But however popular a policy, it won’t bring victory to a party destined to defeat or sink a party cruising to victory.

In 2001, the Conservatives unveiled tax cuts that performed strongly with voters, but the party still lost the election heavily. The same is true in 2005 when the Tories pushed popular policies on immigration and asylum seekers but the party fell well-short of power. Again in 2015, Ed Miliband’s energy price freeze fared well in the polls, but the Labour party went backwards in the subsequent election.

Following the leak of Labour’s 2017 election manifesto, it is likely that some will point to the popularity of individual policies as evidence that Labour will see a surge of support and so take power on June 8. However, if voters are unsure of the party and the politician pushing the policy, arguably it doesn’t really matter whether something such as rail renationalisation gains favour with the public.

In successful election campaigns policy only comes into play once a party and leader have passed three key hygiene tests: 1. Connecting on core values; 2. Positioning on the big issues of the day; and 3. Leadership. This was as true for Tony Blair’s general election win in 1997 as it was for Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership victory amongst party members in both 2015 and 2016.

However, when it comes to the Labour party leader facing the whole electorate in 2017, it is unlikely that any policy will deliver victory as many voters have already made up their minds on these hygiene tests.

Core values

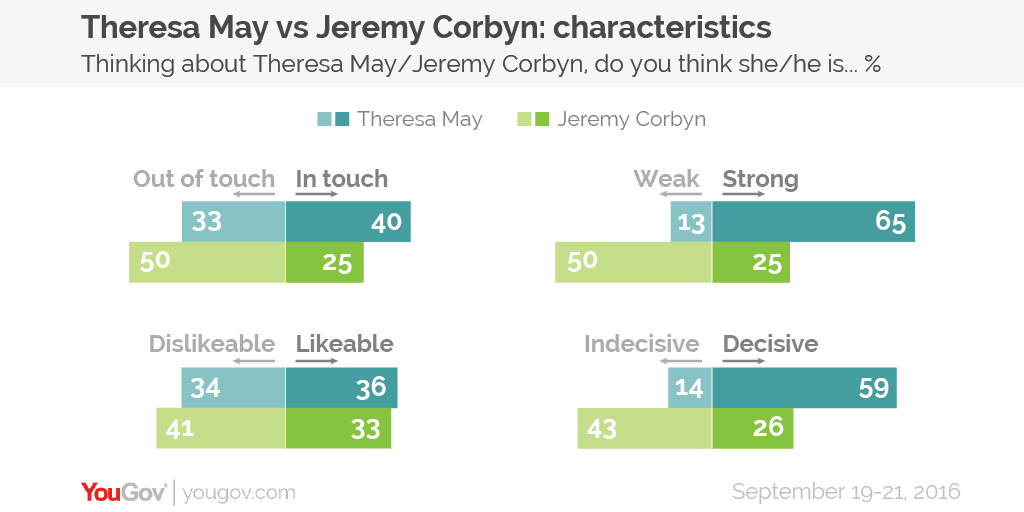

In terms of core values, many voters, either consciously or subconsciously, will refuse to even give a party a fair hearing on the big issues of the day or take their leader seriously as a possible prime minister if they don’t pass the basic smell test. This comes in the form of whether they believe the leader or party meets their standards when it comes to core values like strength, decisiveness and how in touch they are with voters.

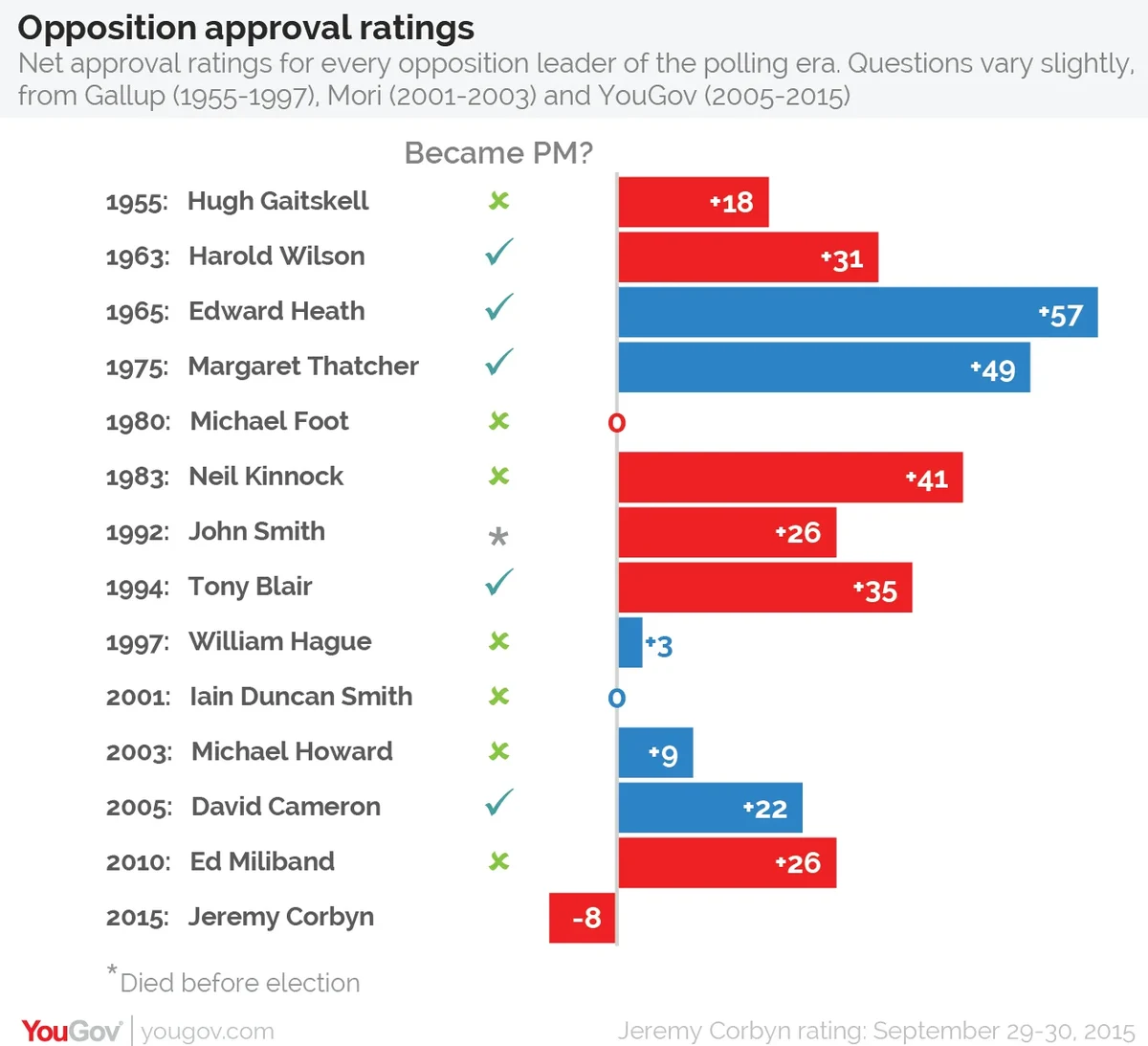

If a leader and their party don’t perform well across most of these areas, then they are less likely to give them consider their views on the big issues. Many voters formed negative views of Jeremy Corbyn very quickly, with YouGov research in 2015 showing him as Britain’s least popular new opposition leader since polling began (see chart below).

There are a range of possible explanations as to why voters formed these snap opinions but most would agree Jeremy Corbyn got off to a tough start, such as when it was reported he hadn’t sung the national anthem (and a majority of voters said he was wrong to fail to sing it).

Big issues

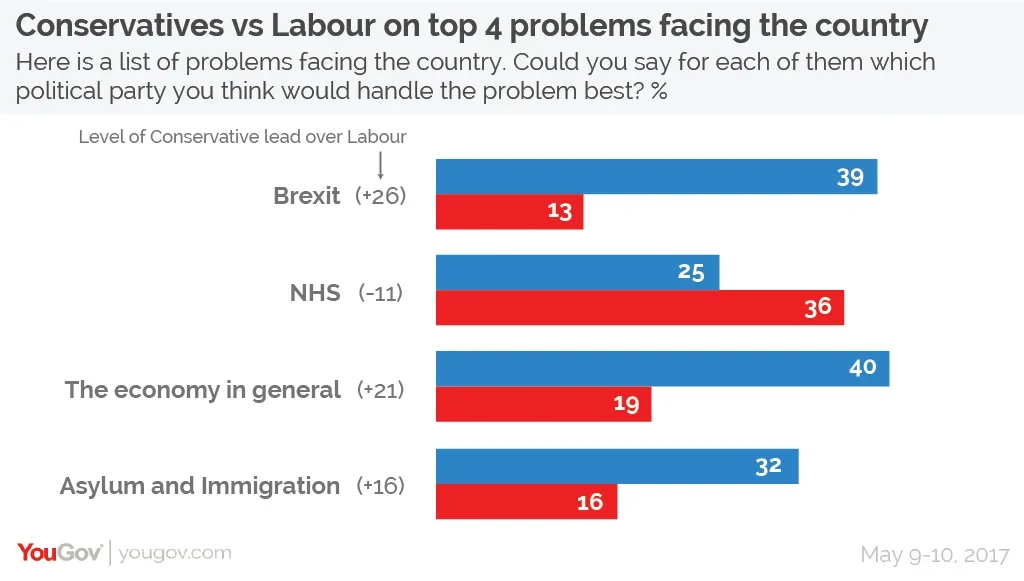

While the specific “most important issue” changes from election to election, our latest issues tracker shows that this time round Brexit, the NHS, the economy and immigration are at the forefront of voters’ minds. The electorate needs to know where a party stands on an issue and whether they trust them on it. Brexit is arguably a super issue at this election that wraps up many other things – like the economy, security and immigration – into one.

In 2017, Labour leads on only one of these issues – the NHS – and lags badly when it comes to the super issue of Brexit. Even when it comes to the National Health Service, while the party leads the Conservatives overall, it falls behind if the public is presented with a choice between an NHS run by Theresa May (29%) versus one run by Jeremy Corbyn (26%). Even when assessing the major issues, and the ones where Labour has traditionally held the better cards, the question of leadership infects the voter’s view of the issue.

Leadership

All of this adds up to voters’ views of the leaders – or, as some view it, the “personality” side of politics – and this is an important factor in how people vote. The truth is that, while many people who work in and around Westminster are endlessly fascinated by politics, most voters aren’t. Instead, many take shortcuts, assessing a party’s core values and where it stands on the big issues and seeing that both are embodied in its leader.

In most cases, when a party is set for victory it will be outperformed by its leader. In hindsight, this was evident in 2015 when David Cameron significantly outperformed his party while Ed Miliband trailed his. Approaching this election, Theresa May is comfortably outperforming the Conservatives, while the opposite is true for Labour and Jeremy Corbyn.

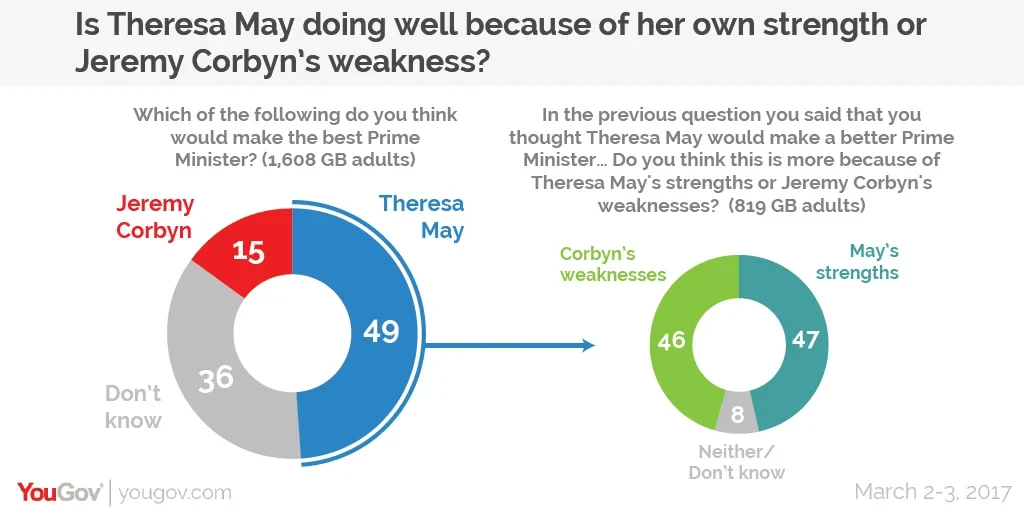

Naturally, people don’t view a leader in isolation, they view them in comparison against the alternative. In 2017 this makes for more bad news for Labour and Jeremy Corbyn. A couple of months ago when we asked who would make the best Prime Minster, our poll showed Theresa May with vastly more support than Labour’s leader.

We then asked whether people supported May because of her strengths or Jeremy Corbyn’s weaknesses, and found it split straight down the middle. It is clear that to many voters, part of Theresa May’s strength comes from Jeremy Corbyn’s perceived weakness as a leader.

Policies don’t matter in isolation

This is not to say that policies don't matter or that they don't affect voters – they do. However winning election campaigns join up core values, big issues and leadership, using policies as an illustration of these forces, rather than a replacement for serious weakness in these areas.

Jeremy Corbyn himself exemplified this approach in 2015 and 2016. His core values matched those of Labour party members and they backed him on what they considered to be the big issues facing them, both of which created, and then reinforced, an unshakeable faith in him as their leader. His policies were embodiments of these factors whereas for his opponents in those contests they appeared to be substitutes.

It is a different situation in a national election, however, when the target audience are the general public rather than party activists. Policy announcements can’t make a voter believe a party shares their values, is with them on the big issues, or give them faith in a leader they perceive as weak, out of touch, and a poor choice of Prime Minister. When parties look to manifesto launches to reverse their poll fortunes it is likely that it is already too late and no policy can save them.

Photo: PA