While we should not enslave ourselves to history, neither should we ignore it: recent history contains a bleak message for Jeremy Corbyn

In politics, as in those personal finance ads, the past does not always provide an infallible guide to the future. Five months ago, David Cameron defied the rule that Prime Ministers never increase their party’s vote-share after a full parliamentary term; he became the first person to do so since Lord Palmerston 150 years ago.

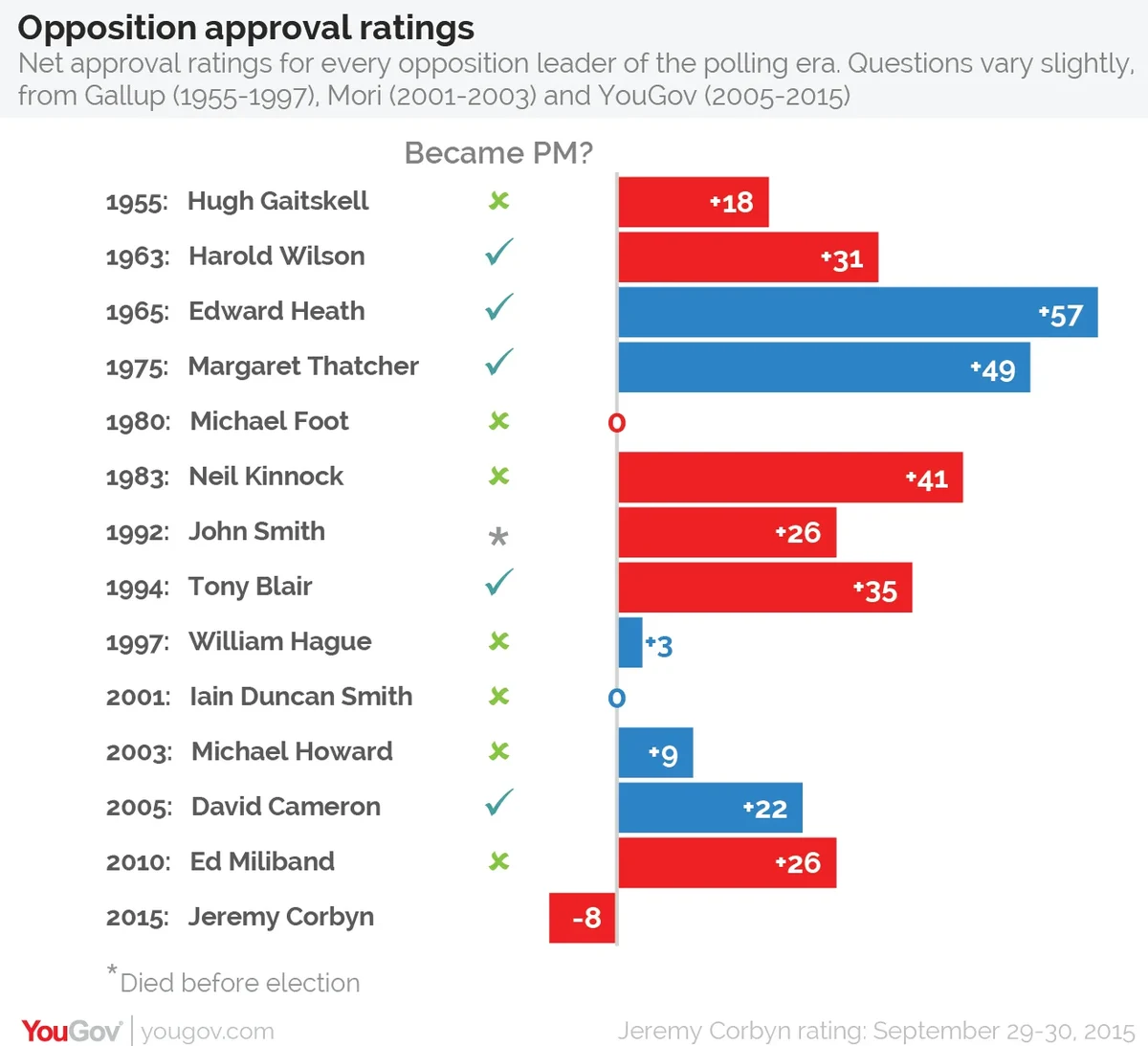

Opinion polls have been measuring the ratings of opposition leaders since the Second World War. The first incoming leader of the polling era was Hugh Gaitskell, who succeeded Clement Attlee as Labour’s leader in 1955. Here are the initial ratings of every opposition leader since then. The questions have varied slightly, from Gallup, Mori and YouGov, but in each case we show the net rating, subtracting the negative score from the positive score.

The most obvious point is that YouGov’s latest poll for The Sun shows that Corbyn is the first new opposition leader to have a negative initial rating. With two, Michael Foot and Iain Duncan Smith, the positive and negative scores were in balance. Everyone else started out with a positive score – even Ed Miliband, whose initial plus 26 contrasted with his dire ratings later in the 2010-15 parliament.

The second point is that no new opposition leader whose initial rating was less than plus 20 has ever become Prime Minister. The list of leaders with lower ratings provides a roll-call of failure: Gaitskell, Foot, Hague, Duncan Smith and Howard. For Corbyn to have a substantially worse rating than any of them is a measure of how much he must do to lead Labour to victory.

Not every leader with an initial rating of more than plus 20 went on to become PM – look at Kinnock’s rating as well as Miliband’s. (John Smith, who started out with a net rating of plus 26, did not get to Downing Street either; but he died before he could fight an election, so can’t really be counted as either a successful or unsuccessful leader.)

There is, I think, a reason for this pattern, and why history will be hard for Corbyn to defy. Many voters give new opposition leaders the benefit of the doubt. They see a fresh face that they often don’t know much about. They hope the new leader will become a credible national leader. Sometimes the new leader justifies their faith; Tony Blair’s rating on the eve of the 1997 election was plus 51. More often, the doubts grow – most spectacularly with Michael Foot (minus 60 on the eve of the 1983 election) and Neil Kinnock (minus 30 in 1987).

History, however, provides no example of a party leader with a relatively low initial score significantly improving on their rating. For the stock of goodwill to grow, it needs to start strongly. Just as party ratings follow a conventional rhythm, with oppositions having the chance to exploit the unpopularity of governments in mid-term, so do the fortunes of party leaders. For an opposition leader to have a real chance of victory, they and their party must both be well ahead of their rivals by mid-term. Opposition leaders with a low starting score have never managed to achieve the kind of mid-term cushion that enables them to withstand the recovery that governments and prime ministers normally enjoy as the following election approaches.

To repeat, history can never be regarded as an infallible guide. But I would not place any money on Corbyn becoming Prime Minister. And if he is to prove me wrong, I reckon he can’t wait until 2020 to persuade voters he is up to the job. His rating needs to move strongly into positive territory by the end of 2017 at the latest.

PA image