Popular policies put forward by leaders who lack public credibility can end up losing more votes than they gain

For obvious reasons, politicians love to claim that their policies are popular. The more they can show that they are on the side of the voters, the easier it is to win votes. Jeremy Corbyn thinks he is onto a vote-winner with his plan to renationalise Britain’s railways. Is he?

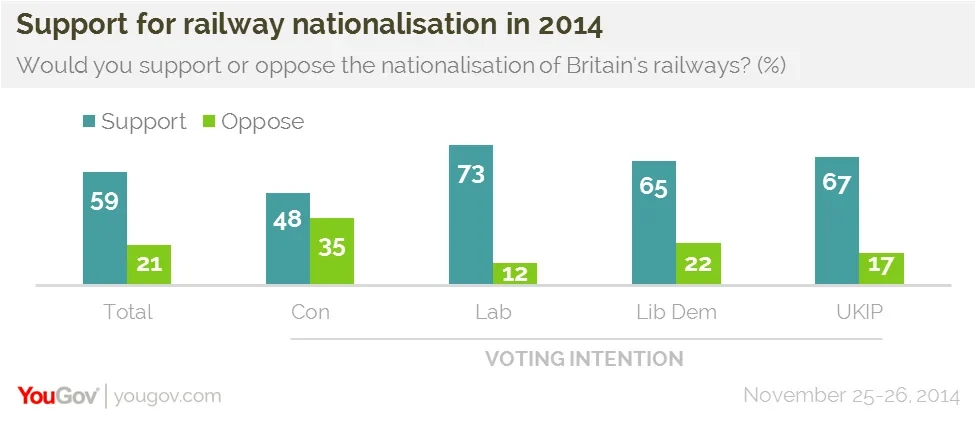

The case for saying yes is contained in YouGov data down the years. The last time we asked specifically about it was last November. 59% told us they supported renationalising the railways; just 21% were opposed. Even Conservative voters divided 48-35% in favour. Voters also back another of Corbyn’s ambitions: to renationalise Britain’s gas and electricity companies. Our latest survey for the Sunday Times finds that the public backs this by 50-30%.

It’s worth noting that Ukip voters strongly support both measures. So Corbyn could argue that his policies would help win back the working-class voters that preferred Nigel Farage’s party to Ed Miliband’s in May.

However, here are three reasons why nationalisation may not end up winning Corbyn many votes.

First, debate has not yet been joined. Voters are reacting to what they see as the failures of the railway and energy industries – the perception of high prices helping to line the pockets of shareholders and senior managers. (It’s the same with banks – public hatred of the bonus culture lies behind a widespread desire to see the state retain its shareholdings in the banks it rescued.)

What we have not yet had is the debate about how nationalisation would work. How much would it cost? How efficiently would the state run industries it owned? Would rail and energy prices really fall? Opponents of nationalisation would point to the old days when these industries were in state hands. They were badly run and starved of investment. (When nationalised companies borrow money, this adds to the government’s borrowing requirement. This used to lead to investment cutbacks every time ministers needed ways to save money without cutting back on teachers, doctors or welfare benefits.)

In the last parliament, Labour thought it was onto a vote-winner by promising a mansion tax. Yet, by election day, the tax alienated many people who feared that it was the thin end of a thick, aspiration-sapping Labour wedge. It might just be the owners of expensive homes today, but what about the wider, more modestly successful middle-class families tomorrow? Corbyn could suffer the same fate with nationalisation. Voters may fear that a Labour government led by him could end up controlling far more of the economy and not doing it very well.

Secondly, there is the goose-and-gander problem. If Corbyn’s aim is to set out policies that voters want, then he would promise to cut welfare benefits, massively reduce immigration, back air strikes against Islamic State/ISIS in Syria and declare his undying love for Nato, British nuclear weapons and the monarchy. Far more of Corbyn’s distinctive policies come in the “unpopular” than “popular” column.

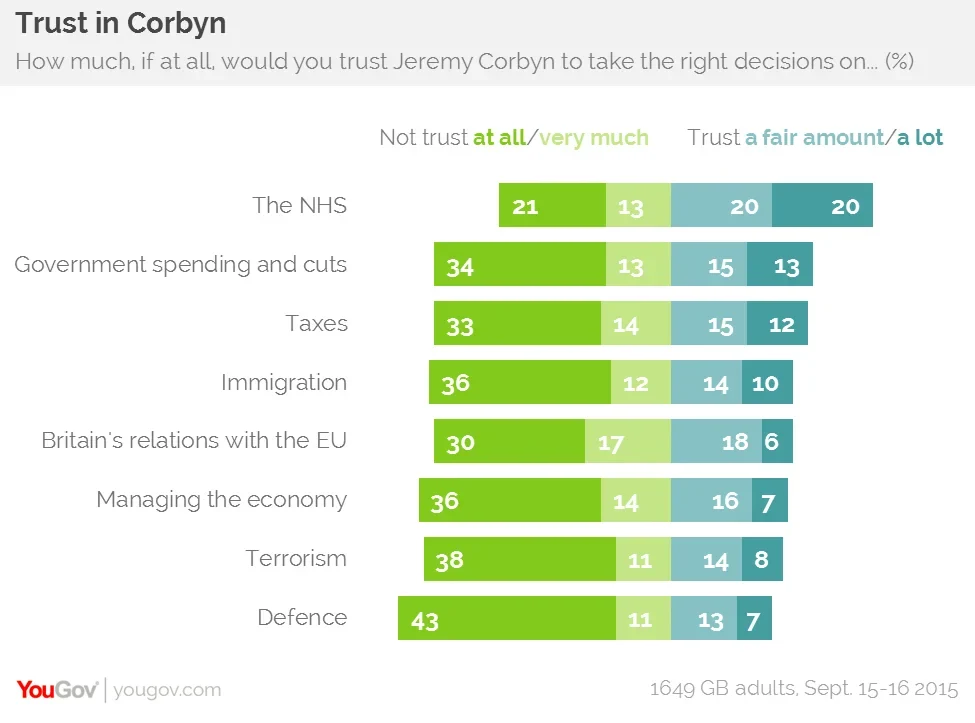

Third, policies cannot be divorced from wider judgements of character and competence. Last week, a YouGov/Times survey asked voters how much they would trust Corbyn on a range of issues. Only on the NHS do slightly more people (40%) trust him ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ than ‘not very much’ or ‘not at all’ (34%). That balance of plus six (40 minus 34), compares with big negative scores on everything else: defence (minus 34), managing the economy (minus 27), terrorism (minus 27), immigration (minus 24), Britain’s relations with the European Union (minus 23), taxes (minus 20), government spending and cuts (minus 19).

If Corbyn is to gain votes from his plan to take over Britain’s railways, he must also persuade voters that he know how to run the economy. Put it another way, if the plan were to have come from George Osborne today – or Gordon Brown in his glory days as Chancellor – then the public might well have backed the idea enthusiastically, for it would be seen as a public interest measure being advanced by people who knew what they were talking about. But – and again, the parallel with the mansion tax is telling – an apparently popular policy put forward by party leaders who lack public credibility can end up losing more votes than it gains.

PA image

See the full Sunday Times results