In the past four weeks support for the union has drained away at an astonishing rate. The Yes campaign has not just invaded No territory; it has launched a blitzkrieg

It’s like Groundhog Day with a savage twist: the same month, same numbers, same shock to the political world – but this time with much more dramatic consequences. Almost exactly four years ago, a YouGov/Sunday Times poll found that Ed Miliband had overtaken the favourite – his brother, David – in the race to be Labour’s new leader. We said he was 51-49% ahead. That is precisely the margin by which Yes now leads No in Scotland.

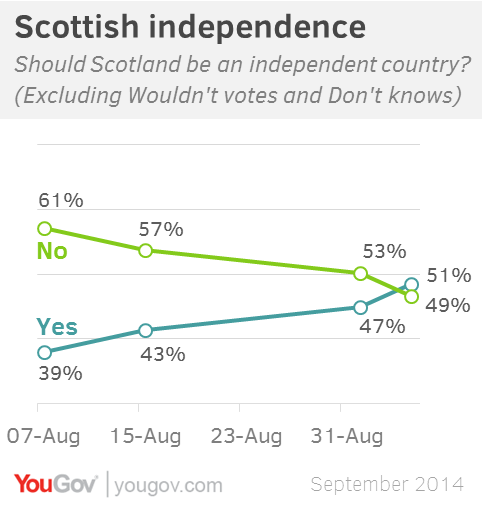

Seldom has the term “knife-edge” carried such lethal force. A two-point gap is too small for us to call the outcome. But the fact that the contest is too close to call is itself remarkable, as Better Together seemed to have victory in the bag. Month after month, they held a steady lead, averaging No 58%, Yes 42%. In the past four weeks support for the union has drained away at an astonishing rate. The Yes campaign has not just invaded No territory; it has launched a blitzkrieg.

Only Conservative voters have resisted Alex Salmond’s advances: 93% of them still plan to vote No. All other sections of Scottish society are on the move, most notably among four key groups:

- Labour voters, up from 18% saying Yes four weeks ago, to 35% today

- Voters under 40, up from 39% to 60%

- Working class voters, up from 41% to 56%

- Women, up from 33% to 47%

These findings suggest that Salmond has achieved three things. First he has neutralised the fear factor. Many Scots thought independence too risky – for example, the uncertainty over Scotland’s currency, and the prospects for jobs and investment. In late June, only 27% of voters thought Scotland would be more prosperous if it left the UK. That figure has jumped to 40%, while those fearing it would be worse off are down from 49% to 42%.

Second, he has played the Sassenach card with great skill. Almost half of all Scots fear that a No vote would leave their country at the mercy of policies they don’t like, imposed by London. Indeed, when we listed the possible downsides in two separate questions, of the two referendum outcomes, subordination to Westminster easily comes top. It appals more Scots than any danger that might flow from independence.

Third, Salmond’s team is thought to have been far more impressive. The No campaign has turned off large numbers of voters. By two-to-one, Scots say Better Together has been negative – and by the same margin, they feel Yes Scotland has been generally positive. This sense that Salmond is offering an optimistic future has energised younger, Labour and working class voters who have switched to Yes in the hope of more progressive policies that London can’t stop.

That said, the contest could go either way in the final ten days. Here are the factors that have the power to decide the outcome.

Factors that could favour a Yes vote

- Momentum. The change in mood of the past four weeks may prove infectious, with more voters being swayed by the excitement and optimism of a surge in Yes support and wanting to go with the flow.

- Superior campaigning. Yes Scotland is not only seen as more positive, it is also winning the ground war. Our poll finds that it has delivered more leaflets, put up more posters, set up more local stalls and sent more emails than Better Together.

- Women continuing to lose their fears of independence. The gender gap has narrowed, but not disappeared. If men don’t start swing back to No, any further shift to Yes by Scotland’s women will guarantee victory for Salmond.

Factors that could favour a No vote

- Turnout. Our poll points to a high turnout among voters of all ages. But experience tells us that the over 60s usually vote in larger numbers than any other group, and they still divide 62%-38% in favour of No.

- Return of the fear factor. Until last week, a Yes victory looked unlikely. Now it is on the cards, the warnings from those opposed to independence will gain a fresh urgency and may make a bigger impact.

- The Quebec precedent. In 1995 Quebec voted on whether to secede from Canada. With a month to go, No held a steady lead. Then the mood changed. The final polls pointed to a 53-47% victory for Yes. But on the day, some voters pulled back from the brink, and Quebec voted to remain part of Canada by 50.6% to 49.4%.

Should Scotland choose independence, then YouGov’s latest Britain-wide poll for the Sunday Times contains bad news for Ed Miliband. As things stand, Labour’s two-point lead would make him Prime Minister, if Scotland remains in the UK. My judgement, taking account of not only the national swing, but a modest incumbency bonus for sitting Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs, is that the result would be something like:

- Labour 316 seats

- Conservative 280

- Lib Dem 27

- Others 27

That would leave Labour just ten seats short of an overall majority, and with the option of going into coalition with the Lib Dems, or running a minority government on its own. But if we exclude Scotland, then Miliband’s hopes evaporate, for the Tories are likely to be the largest party:

- Conservative 278

- Labour 274

- Lib Dem 18

- Others 21

The lesson is clear: next week’s vote could not only change Scotland. It could transform what happens at Westminster.

This analysis appears in the current issue of the Sunday Times