A progressive alliance could get good support among left-of-centre voters but would likely pile up votes where they are not needed

In the wake of Theresa May’s snap general election, Labour and the Liberal Democrats have rebuffed overtures from the Green party for a so-called “progressive alliance” among left-of-centre parties in 2017.

But despite opposition from some significant quarters, the appeal of this type of pact is easy to see. The idea of such an electoral arrangement is that Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Greens (and potentially nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales) would stand one candidate between them in each constituency with the aim of maximising the “anti-Tory” vote.

YouGov analysis among voters in England suggests that while there is a high level of transferability within the “progressive” pool, ultimately the pact would have a hard time securing electoral success. This is because the most enthusiastic supporters of a progressive alliance would add votes where they were least needed to elect left-of-centre MPs.

How voters view electoral pacts

The success of a progressive alliance depends entirely on the willingness of left-of-centre voters to back one of their rivals’ candidates and is based on the premise that keeping the Conservatives out of Downing Street the major motivation of many of those who support “progressive” parties.

Over the past six months we have analysed the viability of a progressive alliance with research being carried out at the end of last year. Subsequently there has been some movement in the levels of support for certain parties, with the Labour and UKIP falling a bit while the Tories and Liberal Democrats have improved their positions slightly.

The outline of a Progressive Alliance

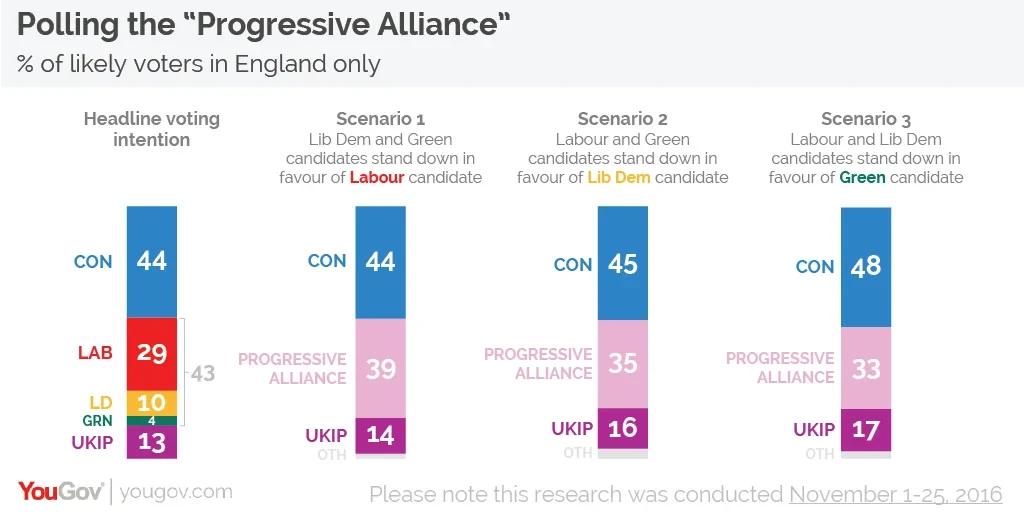

Our research towards the end of 2016 found that 43% of those who were likely to vote in England supported a “progressive” party. The majority of this 43% was made up of Labour (29%), followed by Liberal Democrats (10%) and then the Greens (4%). Meanwhile, the remaining 57% consisted of Conservatives (44%) and UKIP (13%).

Those supporting the left-of-centre parties were presented with three different scenarios for a progressive alliance: one where only a Labour candidate stood, one were only a Liberal Democrat ran and another where the pact was represented by a Green.

The results suggest that Labour would be the most popular choice to front a Progressive Alliance, which makes sense given their voters make up the bulk of the pool supporters. With a Labour candidate representing a left-of-centre pact, the progressive alliance received 39% of the vote compared to the Conservatives on 44% and UKIP on 14%.

Using a Liberal Democrat or Green candidate was less effective. With a Lib Dem heading the ticket, support for the Progressive Alliance falls to 35%, while the Conservatives and UKIP rise to 45% and 16% respectively. The Green-led scenario was worse as just 33% would vote for the Progressive Alliance candidate compared to 48% for the Conservatives and 17% for UKIP.

Lukewarm support

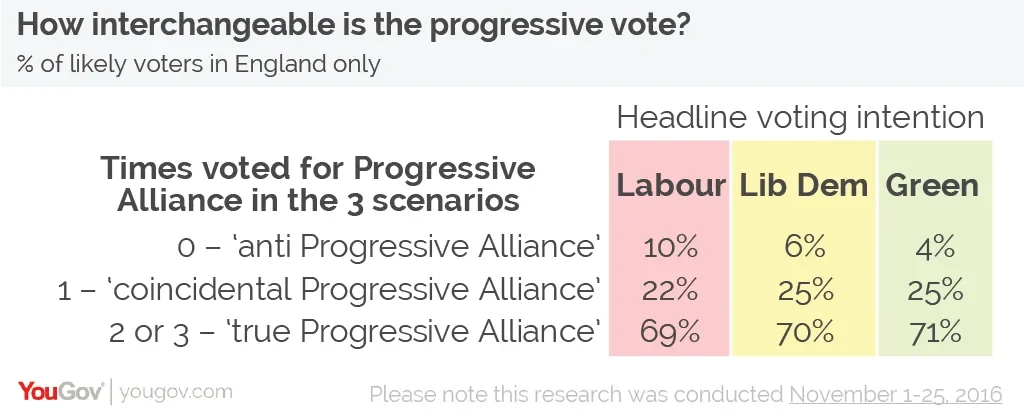

Our data suggest that about half of the pool of progressive alliance votes is directly interchangeable – with 50% willing to back whichever party’s candidate is representing the pact. A further fifth (19%) would vote for an alliance candidate from two of the three parties. In total, seven in ten left-of-centre voters are “true Progressive Alliance” supporters and could, to varying degrees, back some form of pact.

Approaching a quarter of “progressive” voters only backed an alliance in one of the scenarios and, unsurprisingly, in the vast majority of instances this was the party they supported in the headline voting intention. A small proportion of left-of-centre voters reject any form of pact with other parties and would refuse to vote even for their own party’s candidate if they were fronting a progressive alliance.

Lots of votes...but maybe the wrong type of voters

While these raw percentages give an outline of the levels of support for a left-of-centre alliance, as the UK doesn’t use a proportional system in elections they only provide a rough indication of a pact’s success. What is more important is whether a progressive alliance would get support in the right constituencies to deny the Conservatives the seats to form a stable government.

Looking deeper into the data it appears it would not, as this electoral coalition is both too wealthy and too young to win the specific type of seats it needs.

Seven in ten (70%) of those who are “true” progressive alliance supporters (the people who would back a pact in the majority of cases) come from the ABC1 socio-economic group. In general terms, such voters tend to be concentrated in the safest seats – both Conservative and Labour ones with larger majorities. By contrast, the seats Labour lost to the Conservatives in 2015 – that might have been saved by a progressive alliance – contain a disproportionately larger share of C2DE.

There is a similar problem for it with younger voters. This group is significantly more likely than older voters to back an alliance. Just 12% of ‘true’ progressive alliance voters are aged 65 or older, compared to 16% of 18-24 year olds and 48% of 25-49 year olds. As younger people historically are far less likely to turn out than their elder peers, that such a large bulk are under-30 limits the potential electoral effectiveness of a left-of-centre pact.

Using Brexit as a rallying cry could also have limited use. Although it seems logical to rally Remain voters around single candidates in seats, as with the ABC1/C2DE split, Chris Hanretty’s seats analysis indicates that Remain voters are again tend to be concentrated in places that already have Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green MPs already.

Conclusion

Although the Labour and Liberal Democrat leaderships have poured cold water on a progressive alliance, the concept has been around for decades and is unlikely to disappear any time soon. Despite the unlikelihood of such a pact coming to fruition in 2017, and the practicalities of forming one remaining as formidable as ever, the longer the Tories dominate the political scene the louder voices calling for an alliance are likely to get.

While much will change in the political landscape between June 8 and the following polling day, the data indicates that something significant may have to shift to make any progressive alliance work electorally.

Photo: PA