At six o’clock on Thursday evening the giant energy firm EDF announced that it had agreed to go ahead with the building of a new nuclear power station at Hinkley Point in Somerset.

Two hours later the British government said they wanted more time to study the contract and no decision would be made until the autumn. Nobody had seen this coming and there are now serious questions being asked over the future of what would have been the most expensive building on the planet.

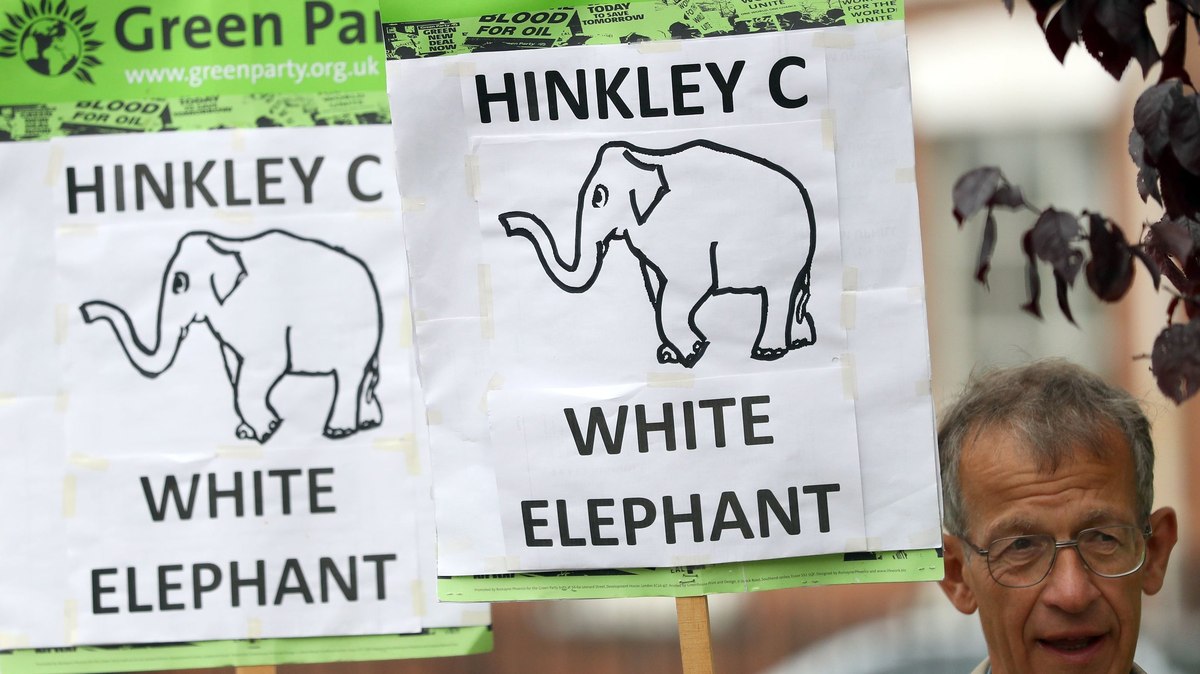

The plans to build Hinkley C date from 2008 and have been controversial from the beginning. They have grown ever more controversial over the years. Champions of the scheme say that Britain’s energy industry is in such a parlous state that without a without a massive new nuclear power station the lights could well go off simply because we aren’t generating enough electricity to match demand. But critics say almost everything about Hinkley is wrong. Who’s right?

Major infrastructure projects notoriously take forever to get off the ground, but building a new nuclear power station is in a class of its own. It’s over ten years since Tony Blair’s government committed Britain to a new generation of nuclear power stations, but none has yet been built. More than three years ago the coalition government gave official backing to the idea of building one at Hinkley Point with the prospect that it would be pumping out electricity by next year. But delay has followed delay and several times it seemed the whole project would bite the dust. Now, however, it seems that there is no turning back.

There are few things that those who support Hinkley and those who oppose it agree upon, but one is that Britain certainly needs more electricity-generating capacity. Power stations from the first generation of nuclear power are coming to the end of their lives - though some have been required to keep working long after their original decommissioning date. Plans to phase out coal-powered stations by the mid-2020s, as part of our commitment to tackling climate change, mean that we can no longer rely on coal. And although renewables, such as wind and solar power, have been making big strides in recent years, few people think they can match all our needs in the foreseeable future. Up to now the gap has been filled by gas. But gas-generated electricity churns out climate-threatening carbon too and most of the gas has to be imported - much of it from Russia.

So the obvious answer, we are told, is nuclear A new generation of nuclear power stations, say its advocates, is good for the climate change and would be reliable - unlike renewables, which depend on whether the sun is shining or the wind is blowing. It would also mean not having to rely on countries that might decide to turn off the tap one day. Hinkley Point alone is planned to supply 7% of our electricity needs, or enough for five million homes, once it is fully up and running.

But opponents of the scheme have a long list of objections. The most fundamental is to nuclear power itself. Those who argue this say that nuclear power remains far too dangerous for human beings to play with. The evidence of the nuclear power station disasters at Chernobyl, back in 1986 and at Fukushima in 2011 (which persuaded the German government to phase out all nuclear power) ought to be enough to stop any government with nuclear ambitions in its tracks, they say. And even without such disasters, they argue, the unsolved problem of what to do with nuclear waste, and the threat it potentially poses for centuries to come, is sufficient to put nuclear beyond the pale.

But even those who don’t take such an absolute view against nuclear power are up in arms about the Hinkley plan. They do so on grounds of the technology that is being proposed and the way the project is to be financed.

Hinkley is to be built by the French utility company, EDF, using the EPR technology of another French company, Areva. The two companies (which are to all intents and purposes one) have already been trying to use this technology at Flamanville, in northern France where the project is years behind schedule, three-times over budget and still not satisfactorily completed. Similar problems are bound to be replicated at Hinkley, critics say.

But it is the financial aspect of the EDF deal that worries so many critics, especially those who think that strategic infrastructure projects, such as power stations, should be built by governments not foreign firms. EDF is a French company 85% owned by the French state. France has for years favoured nuclear power to supply the bulk of the country’s electricity and the French government wants to establish France as an international leader in nuclear power generation. EDF is shouldering two-thirds of the £18billion cost (up from an original £6bn) of building Hinkley; China is investing the other third.

Defenders of the deal point out that 60% of this spending will go to UK construction firms; the building project will employ 25,000 people over eight years, most of them British. But it is the way the French and Chinese will get their money back that has caused most controversy. The coalition government agreed to pay EDF a ‘strike price’ of £92.5 per megawatt hour for the electricity Hinkley will generate over the thirty-five years of the deal. That means that if the wholesale price of electricity falls below this figure, EDF will be reimbursed through subsidy, paid for by the consumer. Originally the government estimated that the size of the subsidy would be £6.1bn, or just £10 a year extra on consumers’ electricity bills. But as the wholesale price has fallen since the deal was struck, the total expected subsidy has risen. The National Audit Office now estimates it at £29.7bn.

There is also real worry about the financial position of EDF itself. It carries debts of 37 billion euros and has had to issue new shares to finance the deal. Its finance chief, Thomas Piquemal, resigned earlier this year on the grounds that he thought the Hinkley deal was financially too risky for the company. The fears seem to be widely shared. According to Mycle Schneider, who used to advise the French government on nuclear matters: ‘There is now a large front inside EDF, inside the nuclear establishment in France, advising against the construction because the sheer size of it could put not only the company EDF at risk, but this could actually put the whole state finances at risk.’

It is the general fall in energy prices that threatens the finances of the deal and makes some argue that it should not go ahead. Professor Nick Butler of King’s College, London, says: ‘The price of every other form of energy is falling. That includes gas, which is plentiful and wind and solar are both coming right down in price. We should step back and review it. The danger of what we are getting into is that we are now locked into a very high price for a very long time.’

So who’s right? Both the French and the British governments (and the Chinese) had seemed convinced that nuclear power must be part of the future of electricity generation and that deals like that at Hinkley are the way forward. But the many critics think it is disastrous in almost every aspect and they believe that the government will be making the right decision if it finally decides to pull the plug. Whose side are you on?

Let us know.