The Conservatives are on course to be the largest party, but it is touch and go whether David Cameron will be able to remain Prime Minister

No pollster or political soothsayer can guarantee what will happen on Thursday. All we can really promise is to raise uncertainty to a higher level of sophistication. The closeness of the Labour-Conservative race is plainly one reason. If today’s polls are slightly out, or there is a last-minute swing, the results may confound all expectations.

But there is another reason. In most elections all we normally have to do is work out what is happening in the Tory-Labour marginals, adding in a glance at the handful of seats the Liberal Democrats might gain or lose.

This time it’s much more complex. Making sense of the Tory-Labour contest is only the start of the task. The Lib Dems are certain to lose many of their seats – but how many and who to? Scotland will provide its own drama: Ed Miliband’s prospects of becoming Prime Minister could depend on whether Labour retains a significant foothold north of the border – or gets wiped out. Finally we have the Ukip factor – not just the seats they are targeting, but the impact their vote has on the Tory-Labour marginals in particular.

In overall terms this means that around 200 seats matter this time – twice the normal number. These are the seats that might change hands, or stay with their current party only narrowly. And one of the few certainties is that both main parties will both gain seats (from the Lib Dems) and lose seats (Conservative to Labour and possibly Ukip, and Labour to SNP). The arithmetic of the new parliament will depend on the net impact of each of these different shifts – any one of which may defy the pre-election forecasts.

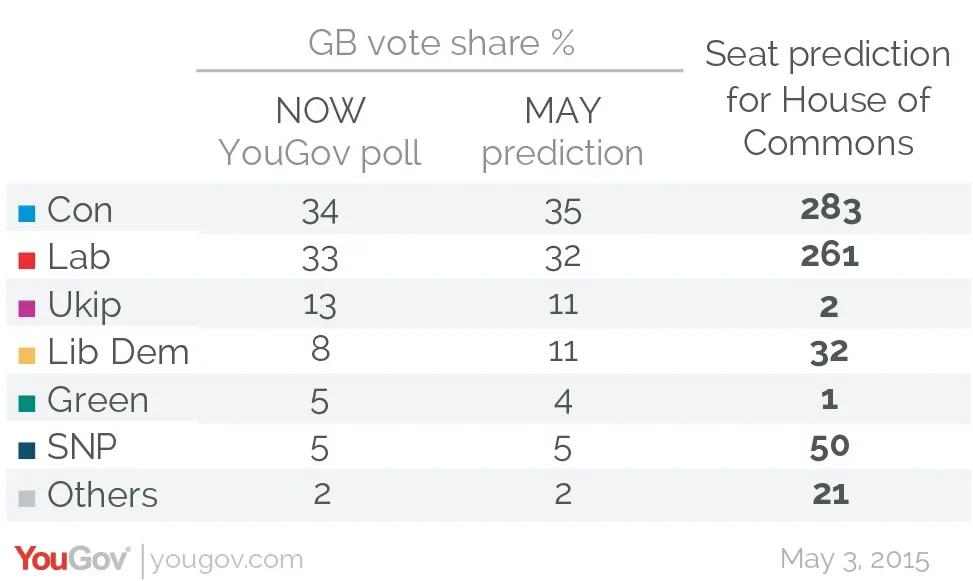

For all those reasons, Britain enters election week in the zone of uncertainty. The Conservatives are on course to be the largest party in the new House of Commons, but it is touch and go whether David Cameron will be able to remain Prime Minister.

YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times confirms the indications of a small shift to the Conservatives in the past fortnight.

If, as I expect, the Conservatives benefit from a further slight gain in support between now and Thursday, they could end up with a modest lead over Labour.

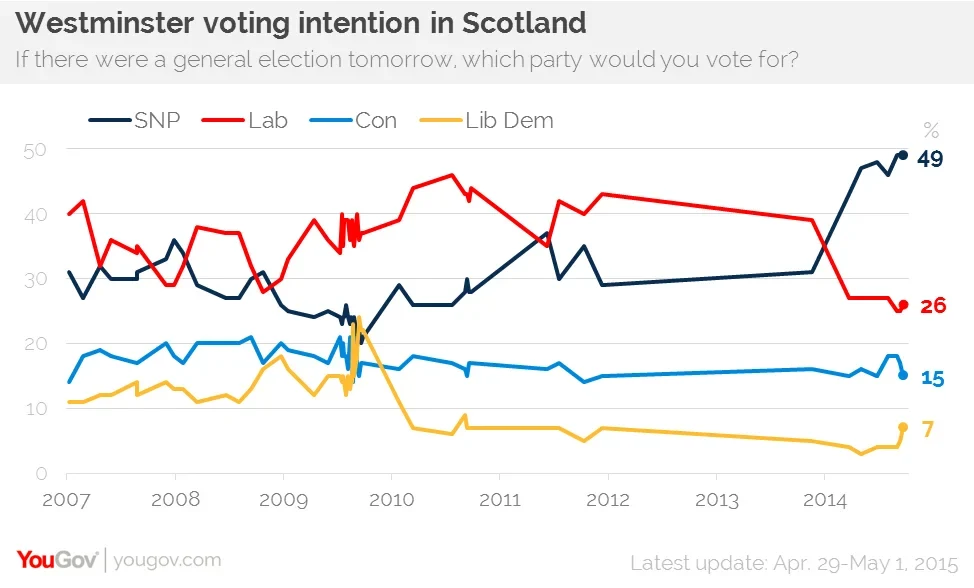

To assess what this would mean in terms of seats, we can draw on two extra pieces of evidence. The first comes from the separate YouGov/Sunday Times survey in Scotland. This shows that the SNP has consolidated its support, with 49% of the vote. Under our first-past-the-post voting system, the party is likely to end up with 50 of Scotland’s 59 seats. Labour looks like to retain only five seats – down from ten in last week’s prediction.

In addition we have analysed the views of more than 50,000 people throughout Britain that YouGov has surveyed in the past ten days. We find that Conservative support is holding up better in its key marginal seats than the rest of the country, and also that the Liberal Democrats are recovering strongly, albeit from a low base, in the seats they are defending.

The upshot is that I have increased the number of seats that I expect the Lib Dems to hold, and reduced the number of seats that Labour is likely to gain from the Conservatives.

The combined effect of these shifts is to widen the Tory lead to 22 seats. Labour may struggle to add to the 258 seats it won five years ago. They are on course to gain 39 seats from the Conservatives and Lib Dems – but lose 36 to the SNP. The party would have to do only fractionally worse to end up with fewer seats than in 2010.

Of course, had Labour managed to retain, say, 30 of the 41 Scottish seats it won last time, Labour and the Conservatives, Ed Miliband would have an excellent chance of leading the largest party after Thursday, and moving into Downing Street.

Instead, as things stand, the future government of Britain could depend on whether the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats continue working together in the new Parliament. Unless the Tories win well over 290 seats, they will have to rely on Lib Dem support. Without it, Labour could end up in power, or at least in government, with fewer seats than the Tories.

Such a deal is likely to depend not just on how many seats the Lib Dems hold, but whether Nick Clegg is one of them. My guess is that he will hold Sheffield Hallam; however, there is likely to be a big variation in what happens in individual seats. This means that my totals may be close to the final result, but individual constituencies are far harder to call.

For the same reason, even if I am right that Ukip wins two seats, I can’t be sure that Nigel Farage will be one of them.

Indeed, it is certain that many seats will be won with tiny majorities. It won’t take much to happen in the final four days of this campaign for the Conservatives and Labour to end up ten seats higher or lower than my figures suggest, or for the Lib Dems and SNP to be five seats higher or lower.

Those tiny shifts would have a huge effect on the future of British politics. At the moment I have no idea who will be Prime Minister a month from now.

This blog is an edited version of commentaries over the weekend in The Times and Sunday Times