Multi-party coalitions could be the new normal

Britain’s political system has metal fatigue. At some point it is likely to crack under the strains it now faces – most recently from Ukip in England and the SNP in Scotland. When it does, politicians from all parties will find the old ways of doing things will simply work no longer.

Just as when an aircraft’s wing snaps off, there will have been a long build-up to the moment of catastrophe. The signs have been visible for years, even decades. But until recently, most Labour and Conservative politicians thought they could carry on as normal, their duopoly protected by our first-past-the-post (FPTP) method of electing MPs.

Sixty years ago, the United Kingdom really was a two-party state. In 1955, Labour and the Tories shared 96% of the vote and 98.5% of the seats. In the 1970s, up to a quarter of votes went elsewhere, most of them to the Liberals, but this made only a modest dent in the combined ability of Labour and the Tories to dominate the House of Commons. Claims of unfairness were countered by the observation that elections did at least produce decisive outcomes.

The inconclusive result of the 2010 election should have told us those days were gone. Yet Labour and the Tories continue to assert that they are competing to form a majority government next May. That prospect grows dimmer by the week. A series of factors are combining to destroy the ability of FPTP to offer a clear choice of government.

- The Lib Dems are now targeting their support more efficiently than in the past. In February 1974, the Liberals won almost 20% of the vote but won only 14 seats. Next May Nick Clegg’s party could well have half as many votes as that, but twice as many seats.

- The politics of Northern Ireland, Scotland and, to a lesser extent, Wales, have drifted away from England’s. None of Ulster’s 18 MPs take the whip of any Britain-wide party. Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s popular new First Minister took office last week with the real prospect that the SNP could gain 20-30 seats next May. And I wouldn’t be surprised if Plaid Cymru adds to its current tally of three MPs in Wales.

- Ukip is mounting a challenge to the traditional parties in England that may yield them up to ten seats next May – and make them serious challengers in dozens more in the election after that. If Ukip next year comes a clear second to Labour in towns and cities across England, it could win seats where the Conservatives have ceased to be real challengers.

Indeed, last week’s by-election showed how vulnerable Labour is to Ukip’s appeal. YouGov surveys show that Labour has been losing working class support to Ukip, not just in Rochester and Strood but across the South. Indeed, the contrast between the Islington-dwelling Thornberry and Rochester’s white van men (and women) reflects a more fundamental cleavage. Labour is far more popular with London’s middle-class voters (where it has 37% support) than working class voters across the rest of the South (just 28%).

In contrast, Ukip appeals to only 9% of middle-class London voters, but is snapping at Labour’s heels among working class voters across the rest of the South, where it enjoys 25% support.

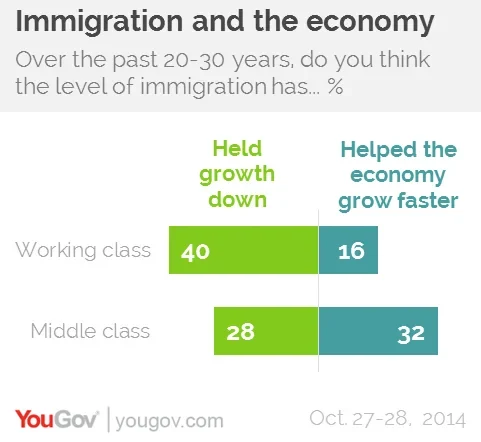

More broadly, it is clear that Ukip’s stand on immigration strikes a chord with working class voters in a way that Labour’s does not. A recent YouGov survey for the Times found that by 32-28%, Britain’s middle class voters think immigration has helped the economy grow faster. But by a large 40-16% margin, working class voters disagree.

However, the same survey found that immigration is not the only issue on which Labour is struggling with working class support. More fundamentally, middle-class voters are broadly happy with the way Britain has evolved since the 1980s, despite the economic strains of recent years, and are optimistic about the future. Working class voters tend to think that Britain has gone to the dogs. As many as 46% would like to turn the clock back 20-30 years, if they could. Only 26% disagree. Labour’s leading lights are plainly comfortable with the diverse culture of Britain today; many of their working-class voters are not.

Add Ukip’s rise to the Lib Dem, Scotland, Ulster and Wales factors, and there could be up to 100 MPs next May that sport neither red nor blue rosettes. That would mean Labour and the Conservatives fighting over 550 seats. To win a working majority, one of them would need at least 330. That means reducing the other to 220. I can’t see that happening.

Let’s lob in 30 Lib Dem MPs. A modest coalition majority would require either Labour or Tory to defeat the other by a margin of at least 300-250. That’s possible, but by no means certain. And if Ukip bites chunks out of Labour territory in 2020, that year’s government-building arithmetic could be even more complex.

There is, then, a real possibility that, for years to come, at least three parties will need to work together in some fashion to provide stable government. The weekend after each general election could see the SNP, Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionists, and even Ukip, helping to decide Britain’s future. And whatever specific agreement they reach, they will be steering Britain’s constitution through uncharted waters.

Or rather, they will be navigating waters that are familiar to much of our continent, with its widespread experience of multi-party coalitions. Maybe Nigel Farage’s lasting contribution to Britain’s political system will be to help make it more European.

PA image

This is an extended version of a commentary in the latest issue of the Sunday Times.