(This article was first published by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change here)

The rise of modern populism has been accompanied by a proliferation of sweeping theories on the public state of globalisation, which often reduce it to notions of a fundamental clash between progressive defenders of an open world versus illiberal advocates of a closed one.

This kind of generalisation is challenged by recent findings from the YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project, an annual study of attitudes in 25 countries, produced by YouGov in collaboration with researchers at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, as well as the University of Cambridge and the Guardian.

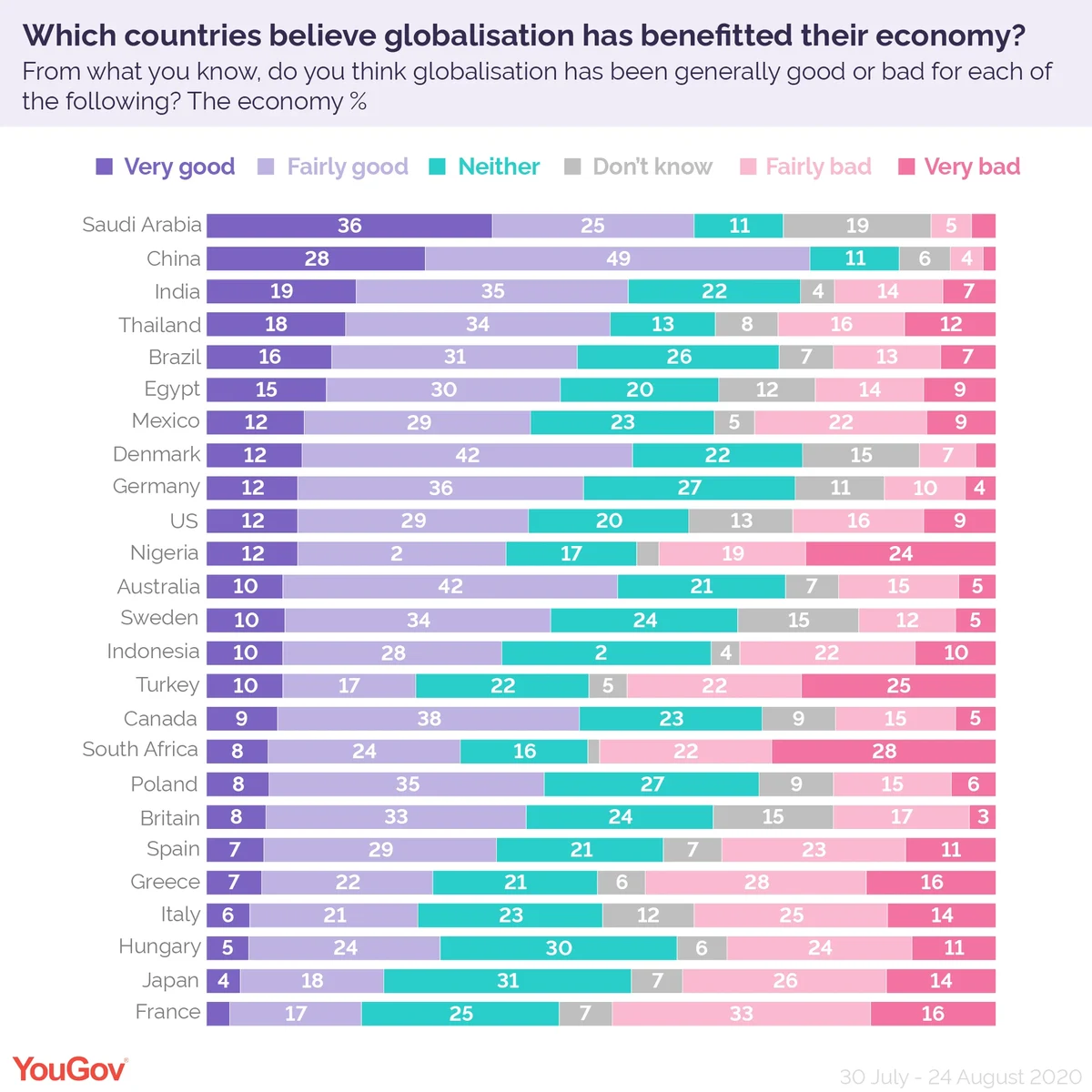

As findings show, attitudes to global engagement are typically nuanced across the political spectrum, rather than polarised. In fact, majorities tend to reflect a mix of neutral to positive sentiment, rather than outrightly negative, towards the perceived impact of globalisation on various aspects of life. In Britain and the US, for instance, more than 60 per cent think the economic impact on their country is either good (41 per cent in each case) or neither good nor bad (24 per cent and 20 per cent), compared with only 21 per cent and 26 percent saying the effect has been simply negative. We find comparable trends across most countries in the survey, including for other metrics such as the national impact on living standards and cultural life.

By a similar token, political tribes show considerable overlap on the essential merits of global society. Among those who were intending to vote for Donald Trump in the subsequent US election at the time the survey was conducted, 37 per cent said globalisation had been good for their living standards, compared with 48 per cent of Biden supporters. Exactly 36 per cent of both Leave and Remain voters thought the benefits and costs of international trade are about equal for Britain. Just under half of Hungarians who voted for Viktor Orban at the last election, and 54 per cent of Poles who backed the Law and Justice party, think globalisation has been broadly good for their economy.

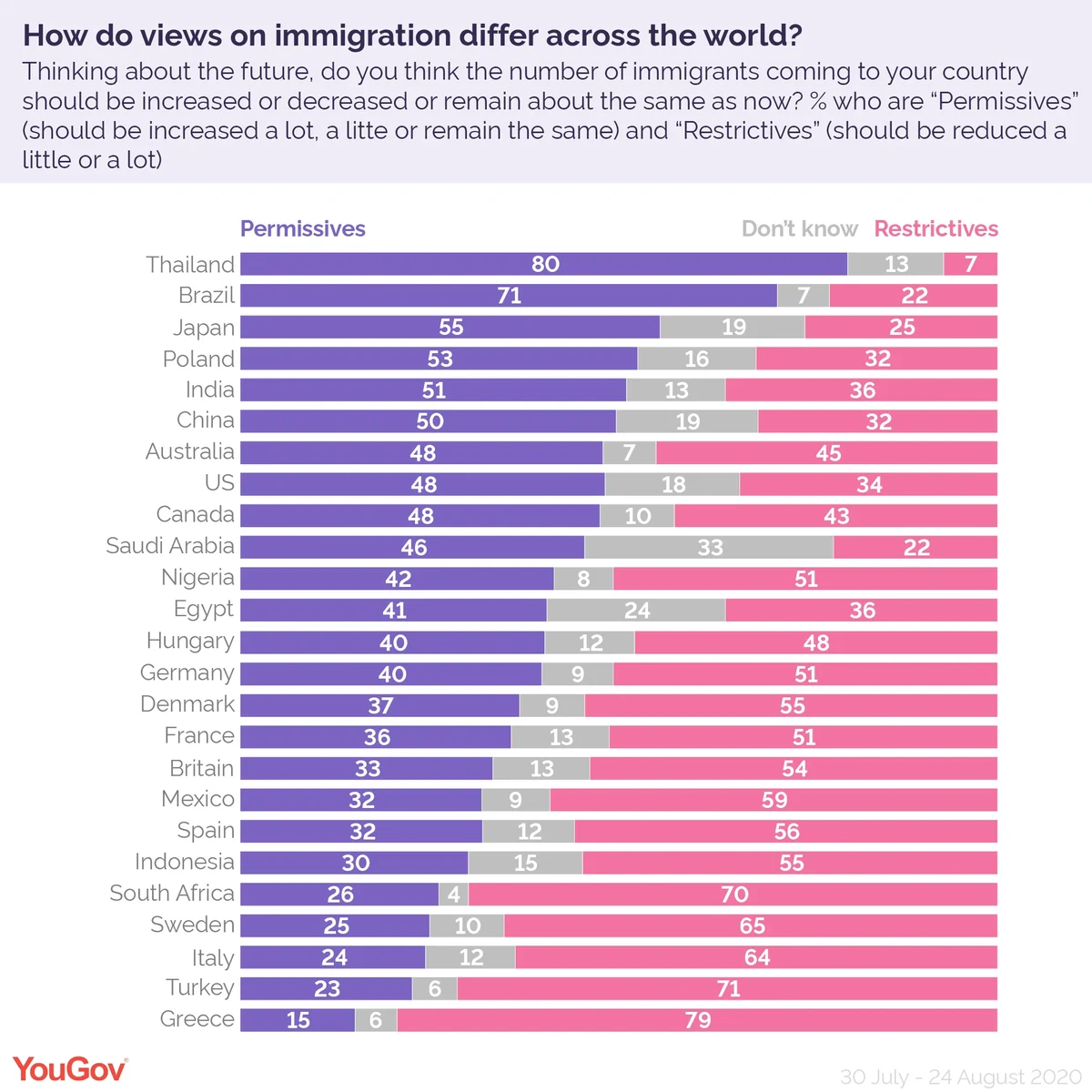

In contrast, however, there are notable levels of concern towards immigration, almost across the board. As other coverage of this survey has suggested, most countries are significantly divided between two broad camps on the issue, which might be described as generally “restrictive” or “permissive”. The former thinks overall levels of immigration to their country should ultimately be reduced; the latter is happy for current levels to continue or even increase.

Some publics are primarily restrictive, such as Italy (64 per cent restrictive versus 24 per cent permissive), Greece (79 per cent versus 15 per cent), Sweden (65 per cent versus 25 per cent) and Turkey (71 percent versus 23 per cent). A couple are heavily permissive, namely Thailand (7 per cent restrictive versus 80 per cent permissive) and Brazil (22 per cent versus 71 per cent). Many are somewhere in the middle, including Britain (54 per cent restrictive versus 33 permissive), the US (34 per cent versus 48 per cent), Australia (45 per cent versus 48 per cent), France (51 per cent versus 36 per cent) and Germany (51 per cent versus 40 per cent).

The scale of the Globalism Project allows for uniquely detailed analysis of these emerging perspectives, which is perhaps more striking for what it shows in common than in contrast. For example, permissives are predictably more likely to think globalisation has been good for the cultural life of their country, but often not by a massive difference, as evident in countries such as France (51 per cent permissives versus 47 per cent restrictives), Spain (52 per cent versus 42 per cent), Italy (59 per cent versus 43 per cent), Poland (54 per cent versus 47 per cent), Egypt (55 per cent versus 42 per cent), India (78 per cent versus 71 per cent), Japan (60 per cent versus 50 per cent), Indonesia (66 per cent versus 58 per cent), Nigeria (65 per cent versus 56 per cent) and South Africa (56 per cent versus 45 per cent).

Similarly on international trade, the larger share of both categories commonly agree that the benefits outweigh the costs for their country or are about equal, such as in Germany (73 per cent permissives versus 60 per cent restrictives), Sweden (73 per cent versus 63 per cent), Denmark (84 per cent versus 69 per cent), Italy (76 per cent versus 55 per cent) and Greece (72 per cent versus 55 per cent). Even on immigration itself, there is crossover, with large majorities or pluralities saying qualified professional migrants are good for their country. In cases where restrictives take a more negative view, permissives often do as well, such as in attitudes towards unskilled labourers coming to their country to search for work.

We also find similar points of consensus around wider issues, such as democracy, environment and social attitudes. In America, for example, 66 per cent of permissives say democracy is generally the best type of political system, compared with 69 per cent of restrictives. Comparable majorities of both groups in all countries agree that climate change is happening and human activity is partly or wholly responsible, including 95 per cent of permissives and 88 per cent of restrictives in Britain. Likewise, most people across both groups share the view that men and women are equally suited to doing all or most jobs.

This is not to deny important differences. Restrictives generally hold more reverence for traditional conceptions of national identity and homogeneity, with consistent majorities who agree that immigration is “generally undermining the national identity” of their country. France, Germany and Britain are typical in this regard, where more than 70 per cent share such a view, compared with only 25 per cent, 17 per cent and 8 per cent of permissives respectively. In research from last year’s Globalism Project, restrictives were much more likely to include “having both parents” born in their country as an important aspect of “being truly” of their nationality. They are also notably more fearful of certain types of immigration, namely unskilled labour, refugees and people joining family members who already live in their country.

Despite having similar views on basic principles of equality, moreover, restrictives are often more likely to shun verbal markers of progressive identity. In Britain, for example, huge majorities of both permissives and restrictives say jobs such as cleaner, hairdresser, nurse, engineer, farmer, doctor and company director are equally suited to all genders. Yet only 16 per cent of restrictives accept the label of feminist, while 72 per cent reject it. Restrictives are also more likely to think political correctness is generally undermining free speech in their country, such as 74 per cent of US restrictives, compared with 31 per cent of permissives.

In other words, large sections of the public are divided over the specifics of immigration more than globalisation in principle, and over conceptions of identity more than underlying values. Maybe the ultimate threat to globalisation, therefore, lies not in the growing hardness or polarisation of public opinion, but rather in our failure to interpret and promote its enduring moderation and commonalities.

More information about the research and results can be found here: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/yougov-cambridge/globalism-project

Image: Getty

Graphics by Eir Nolsoe, YouGov Data Journalist