(This article was first published by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change here)

With a recovering economy and Covid-19 controlled in his country, President Xi Jinping has been keen to emphasise how “the pandemic once again proves the superiority” of China in the world. According to in-depth polling, however, the country’s international reputation may be in decline.

Now in its second year, the YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project is an extended tracking survey of attitudes spanning 25 of the world’s largest countries, produced by YouGov in collaboration with researchers from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, as well as the University of Cambridge and the Guardian.

Compared with 2019, this year’s findings show a marked drop in the number of people who think China plays a positive role in the world, with a difference of at least 20 per cent in numerous countries, including Britain, Australia, Turkey, India, Nigeria and South Africa, and at least 10 per cent in others, such as France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Canada, Brazil, Mexico and Saudi Arabia.

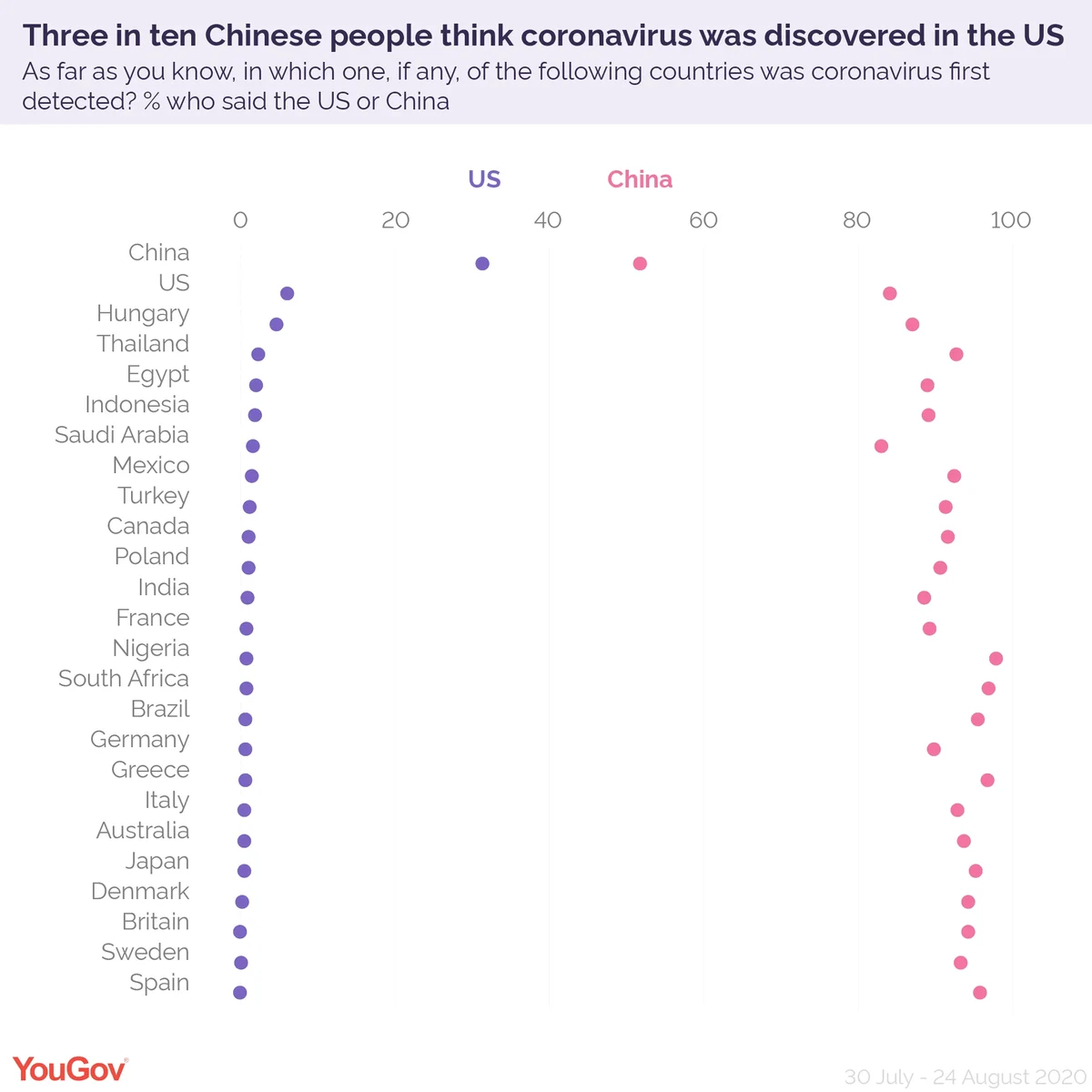

Evidently, the pandemic may have played a significant role in the process. In nearly all countries surveyed, more than 80 per cent of respondents were convinced that Covid-19 originated in China. The one exception was China itself, where just over half (52 per cent) believed the virus originated there, while a third said it came from the US.

Large numbers around the world also share the view that China seriously mishandled its initial response to the virus, in ways that helped to turn the Chinese outbreak into a global one. Clear majorities in all other countries agreed that Chinese authorities initially tried to hide the truth about coronavirus, and that the international spread of the virus could have been prevented if the country had responded more quickly. Majorities in nearly all countries further believed it was definite or likely that the Chinese government punished the doctors who first reported the outbreak.

Some analysts might argue that the downtrend in sentiment towards China is largely related to negative information campaigns in Western countries, and alleged efforts to seek a scapegoat for their own failures to handle the virus. This is challenged by several aspects of the data.

Firstly, these trends are more than a Western phenomenon and duly span the globe, from the Americas and Europe to the Middle East, Africa and Asia. Moreover, they feature in a number of countries where the mood is more positive and majorities of the public think their own government has generally handled the virus well, such as Indonesia (62 per cent), Nigeria (51 per cent), Germany (67 per cent) and Canada (70 per cent). They also include places that are hardly redoubts of a traditionally pro-American or pro-Western perspective, such as Greece and Turkey. In other words, if China has an image problem related to the pandemic, it looks decidedly international and independent of Western-centric perspectives.

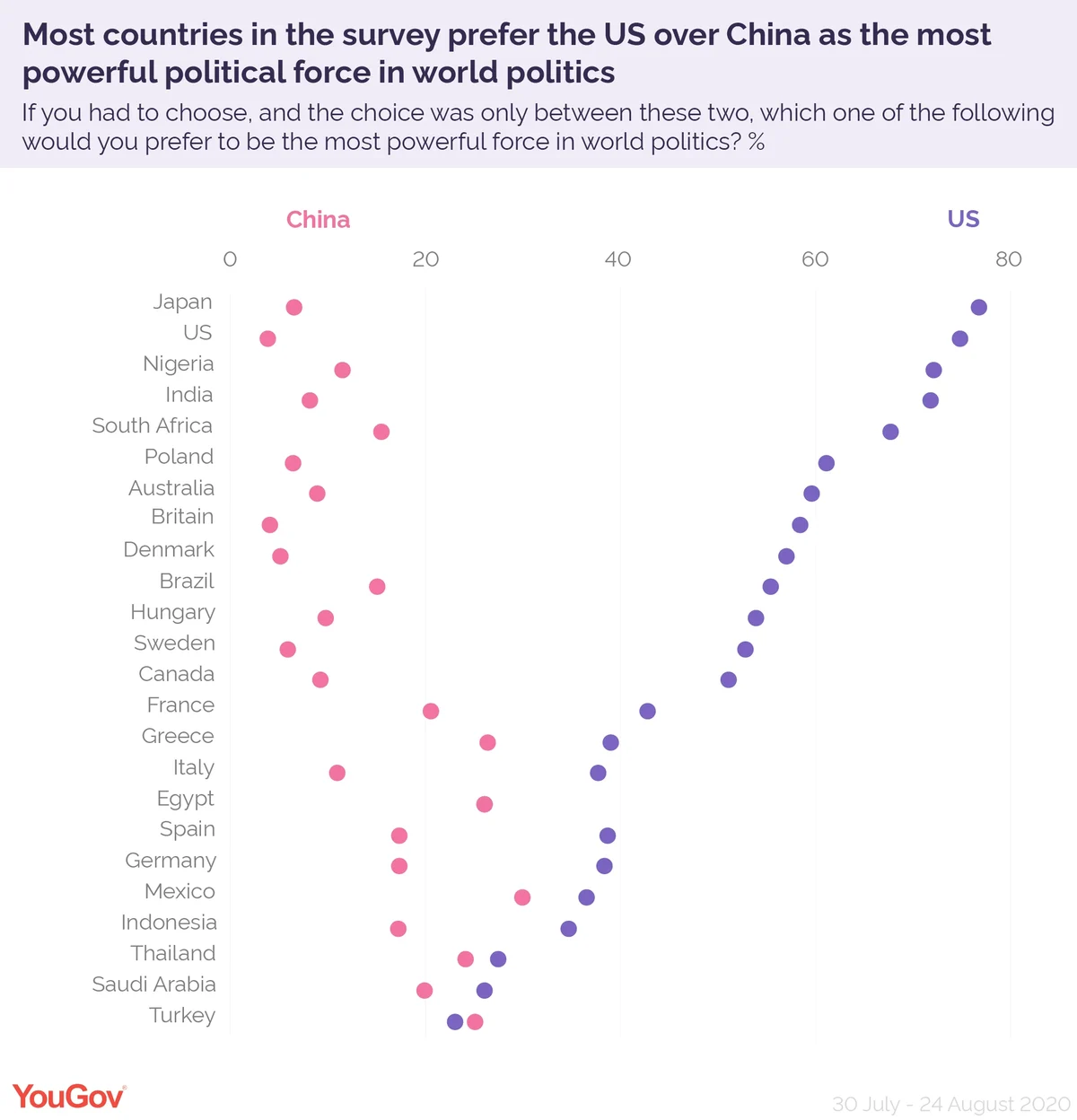

As results further suggest, the Chinese narrative on global leadership currently finds limited public endorsement. Recent years have seen growing efforts on the part of Beijing to portray itself as an alternative source of direction for the international community. This has coincided with a notably more unilateralist phase of US foreign policy under the tutelage of Donald Trump. Yet still in many countries, the larger portion would choose America over China as the country they prefer to be the most powerful force in world politics, often by a substantial margin.

In France, for example, 43 per cent choose the US, compared with 21 per cent for China. This trend repeats across much of the sample, such as Nigeria (72 per cent versus 12 per cent), South Africa (68 per cent versus 16 per cent), Britain (58 per cent versus 4 per cent), Australia (60 per cent versus 9 per cent), Brazil (55 per cent versus 15 per cent), India (72 per cent versus 8 per cent) and Indonesia (35 per cent versus 17 per cent). Only in Turkey (23 per cent for the US versus 25 per cent for China), Egypt (26 per cent for both), and Saudi Arabia (26 per cent versus 20 per cent), do we see less of a clear inclination for America, with more of a balance between the two.

Interestingly, furthermore, in contrast to the question on China’s role in world affairs, most of these figures show limited change from last year, suggesting a certain stability in preference for global leadership. In which case, perhaps this points to a wider challenge for Beijing.

Few doubt the growing, hard power of modern China in economic or military terms. Yet the state of a country’s reputation still rests considerably on the soft power of perceived, common values and inherent, socio-political appeal. As other research from the Globalism Project indicates, for all our differences, many of us still covet a fundamentally liberal world, from the empowerment of individuals to the basic norms and institutions of international society. In which case, China may continue to face a notable disconnect between its desire for public admiration on the world stage and the perceived requirements of maintaining stability at home.

More information about the research and results can be found here: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/yougov-cambridge/globalism-project

Image: Getty

Graphics by Eir Nolsoe, YouGov Data Journalist