Under gender pay reporting regulation, which came into force in the United Kingdom in 2017, all UK companies with more than 250 employees are obligated to publish data every year illustrating the workforce ‘gender pay gap’.

The gender pay gap is the average difference between earnings for men and women across an organisation, industry or country, typically expressed as a percentage of male earnings. This is not, but is sometimes confused with, the concept of ‘equal pay’ i.e. that men and women in the same employment, performing the same job, should receive the same pay.

While unequal pay contributes to the gender pay gap, it is also made up of factors like women being more likely to work in lower paid industries, women’s careers being more impacted by having to take time out to care for children or elderly relatives, and for historical reasons like discrimination decades ago meaning fewer women were able to enter certain industries and are therefore now rare at top levels within those industries.

According to the Office for National Statistics, the gender pay gap among all employees in 2021 was 15.4%, falling from 20.2% a decade ago. In other words, British women are, on average, paid 15.4% less than British men.

With news that the gender pay gap is decreasing, but that it still remains, new YouGov data reveals how far – or not – public opinion on the gender pay gap has evolved.

Britons still don’t actually know what the gender pay gap is, but they do think it exists

In 2018 YouGov tested whether Britons knew what the gender pay gap was, providing definitions for unequal pay and the gender pay gap and asking respondents to choose which one is correct. Back then only 30% chose the correct definition of “women as a whole being paid less on average than men as a whole”. There is no significant difference in understanding between the genders.

Our new survey from December 2021 shows understanding has increased, with 41% now giving the right answer. However, half (50%) still chose the answer describing unequal pay, 3% said the gender pay gap is ‘something else’ and a further 5% didn’t know at all.

While there may be confusion about terminology, the overwhelming majority of Britons think both unequal pay (93%) and a gender pay gap (74%) are unacceptable situations. Notably, however, more think that the existence of a gender pay gap is acceptable (13%), compared to men being paid more for doing the same job as women (3%). Men in particular are more likely to think the existence of a gender pay gap is ok (20% vs 7% of women).

Unacceptable though it may be to Britons, the large majority (78%) currently think a national gap between men and women’s average pay remains, including over half who think the gap is very (11%) or fairly big (46%). Only 4% think there is no gap.

Women are much more likely than men to say they think there is a very or fairly big gender pay gap in Britain (by 69% to 46%). Older people are also more likely than younger adults to think a very or fairly big gap remains (62% of over 50s vs 44% of 18-24 year olds). Likewise, Labour voters are more likely than their Conservative counterparts to think a very big (by 19% to 7%), or fairly big (by 55% to 44%) gap separates the genders’ pay packets.

Among those who think a gender pay gap persists, only one in five (18%) think it is likely that it can be closed in the next five years. More than twice as many (42%) think there is a good chance it can be closed in the next 10 years, while two thirds (68%) think there’s a strong possibility it can be closed in the next 50 years. A pessimistic 15% think it is unlikely that we will ever close the gender pay gap.

Britons are no more likely to think women have equal job opportunities as they were 10 years ago, and have become more dissatisfied with the way society treats them

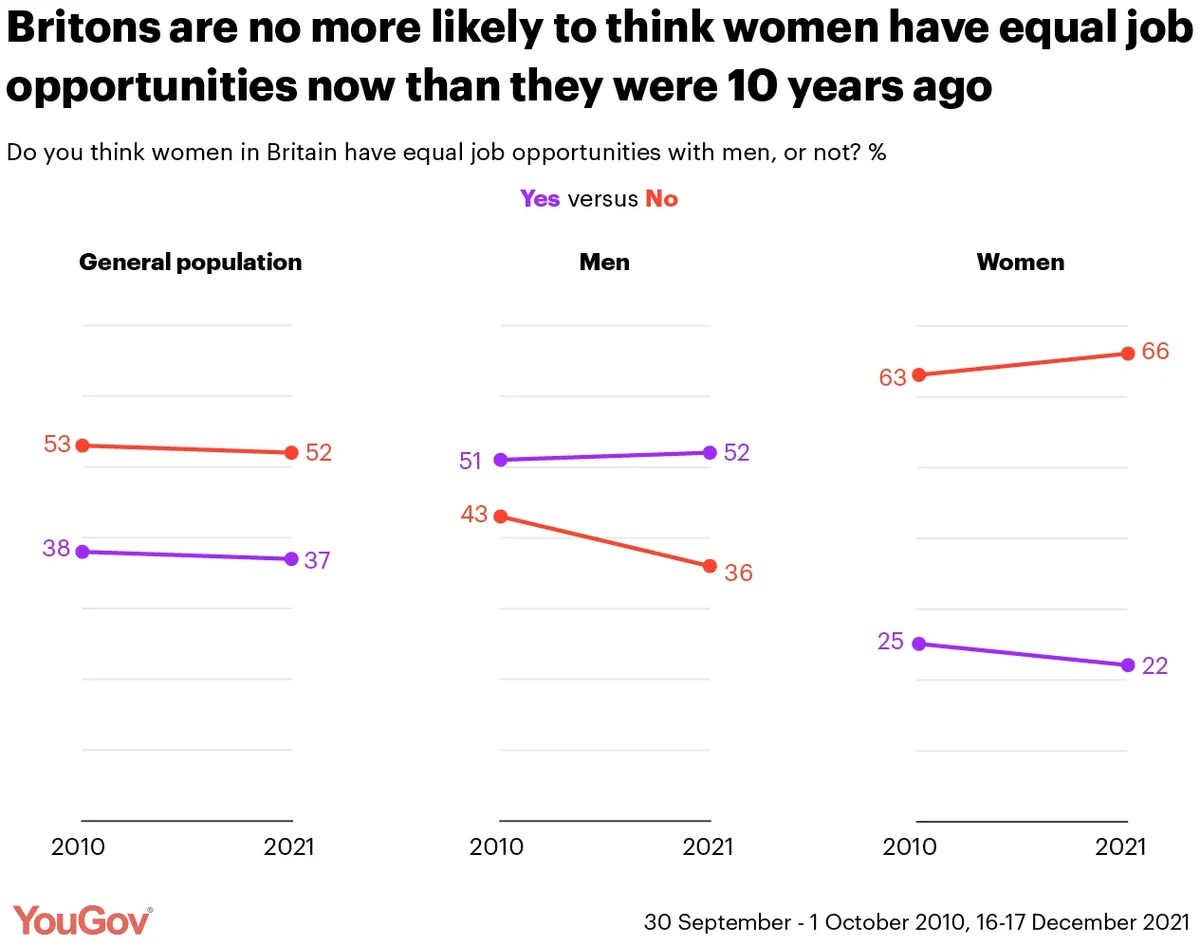

Looking more widely at the causes of the gender pay gap and surrounding issues, a YouGov survey in 2010 found that 52% of Britons thought women did not have equal job opportunities to men (37% thought they did). When asked again this year, our new data shows that these figures remain the same, with 53% believing women lack the same opportunities and 38% believing they have parity.

The gender breakdown on this question has changed slightly, with more men moving from previously thinking women don’t have the same job opportunities (43% in 2010 vs 36% in 2021), to being more unsure (6% in 2010 vs 12% now).

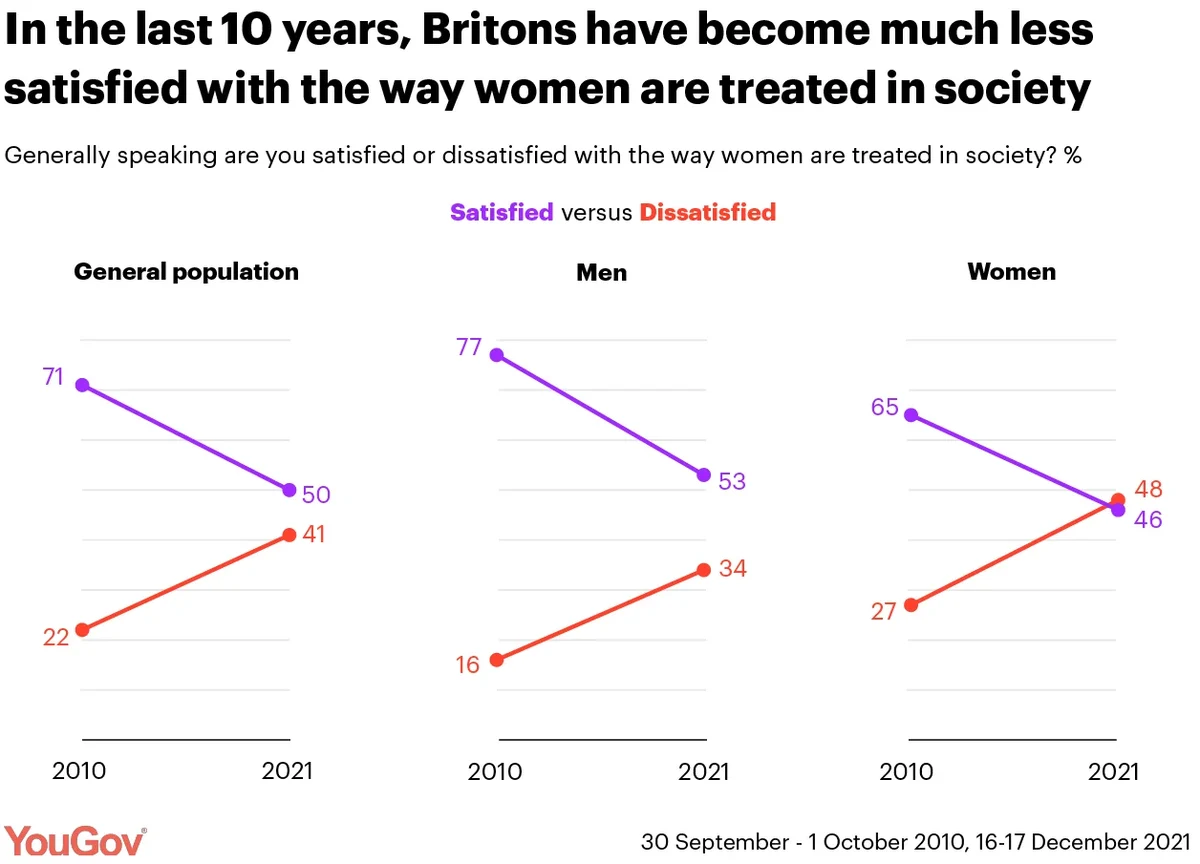

Separately, our 2010 survey found that 71% of the public were satisfied with women’s treatment in society, with only 22% dissatisfied. More than a decade later that positivity has decreased substantially, with only 50% now satisfied and 41% dissatisfied.

Women’s dissatisfaction with treatment towards them has grown by 21 points, from 27% in 2010 to 48% now. Women are now as likely to say they are dissatisfied as they are satisfied (46%). One in three men (34%) are also now dissatisfied with the way women are treated in society, a significant increase from 16% ten years ago.

In what ways is it ok to try and close the gender pay gap?

The evidence is very clear that a gender pay gap exists between men and women, and many companies engage in actions to increase and equalize women’s average pay.

When asked what actions aimed at closing the gender pay gap they support, methods deemed acceptable to most Britons include: actively ensuring gender diversity among colleagues (62%), schemes in education to help girls get into university and higher paid professions (63%) and actively celebrating female successes in work (61%).

Britons are more split on some actions like actively targeting women with job advertisements (39% acceptable, 41% unacceptable) and workplace skills training specifically for women (41% acceptable, 39% unacceptable).

The only method seen as unacceptable by the majority of Britons is all-women shortlists for a job role (65%), which could be argued to fall under the illegal practice of ‘positive discrimination’. Older people are more likely to say this is unacceptable, with 72% of 50-64s and 70% of those aged 65+ saying so, compared to half (50%) of 18-24s.

There is a consensus between what men and women think are acceptable, with these overall patterns holding between genders.