YouGov polling of more than 40,000 people to forecast individual constituency results – using the MRP model which foresaw the 2017 hung parliament – has the Conservatives five points clear of Labour, but only gaining four seats

Rumours abound in Westminster that Theresa May will call a general election by summer as part of plans to force through her Brexit deal. New Statesman reports that several ministers have told their local party associations to prepare for it, and that the Tories are urgently seeking office space in London to free up space at Conservative HQ.

Downing Street has denied the suggestions, although it’s worth noting that it did that last time too.

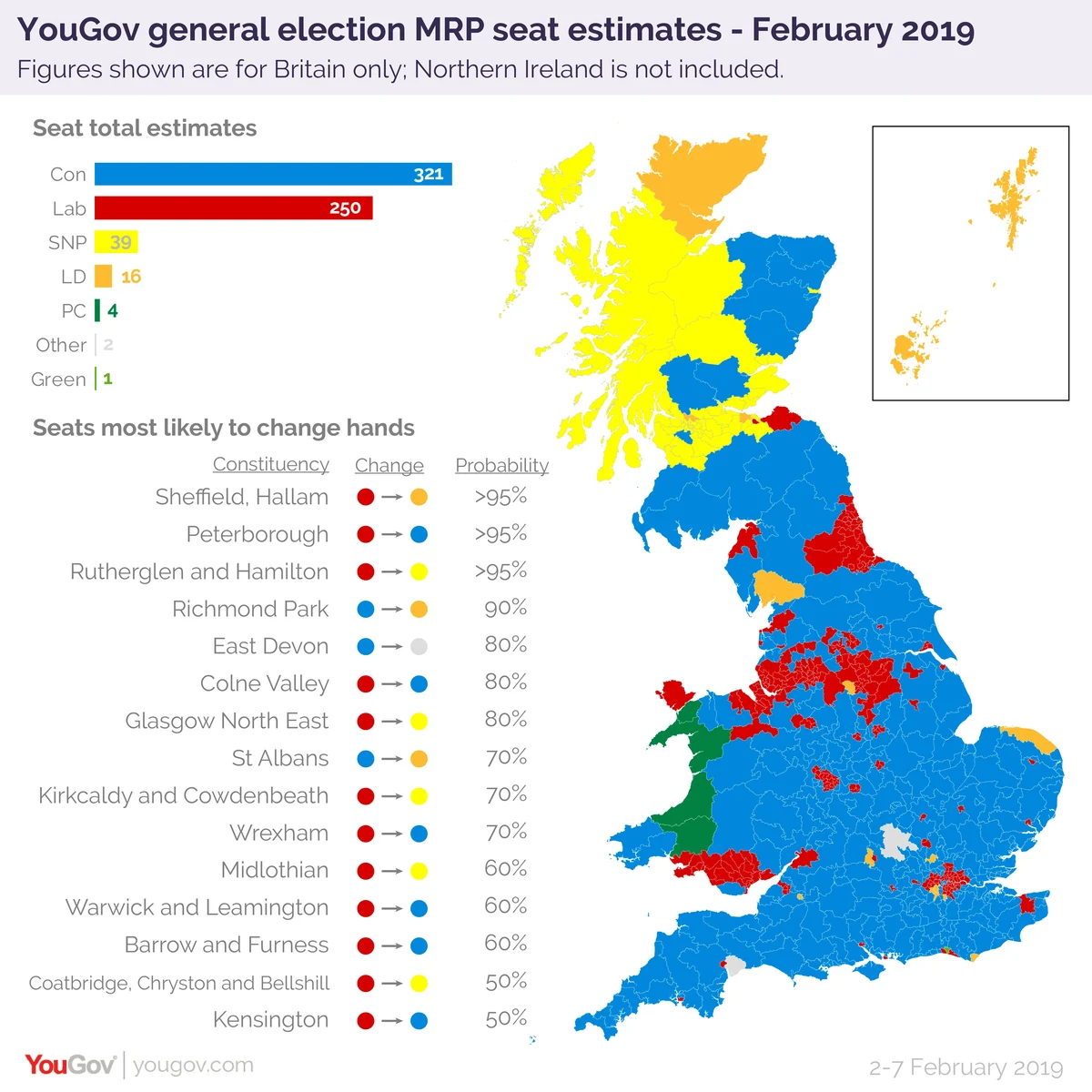

The latest YouGov MRP constituency modelling – the same method which delivered near-perfect projections of a hung parliament in the 2017 general election – reveals that, if an election were to be called, as it stands the Tories would be unlikely to gain enough seats to give the Prime Minister an effective majority.

From the 2nd to the 7th of February we asked 40,119 respondents who they would vote for in the event of a general election, and the results were modelled by Ben Lauderdale and Jack Blumenau of UCL.

The most likely outcome according to the model is that the Conservatives would win 321 seats – just four more than their current tally. Because Sinn Fein MPs do not take their seats, this figure would probably give the Conservatives a working majority, but would not be enough to offset the scores of Tory rebels the PM needs to overcome.

One of the most likely gains for the Tories is Peterborough, a seat which could see a by-election soon as Labour MP Fiona Onasanya was recently imprisoned for perverting the course of justice (but of course, by-elections don’t always follow these national trends). The party also stands a good chance of taking Colne Valley, but also looks likely to lose Richmond Park and St Albans to the Lib Dems.

Labour meanwhile are estimated to lose a handful of seats, down to 250 from their 2017 total of 262. Vulnerable seats highlighted by the model are Nick Clegg’s old constituency of Sheffield Hallam, as well as Rutherglen and Hamilton.

The Liberal Democrats and SNP would each see four further MPs added to their ranks, while the model also suggests the independent candidate Claire Wright could take East Devon from the Tories (although such unusual seats are harder to model).

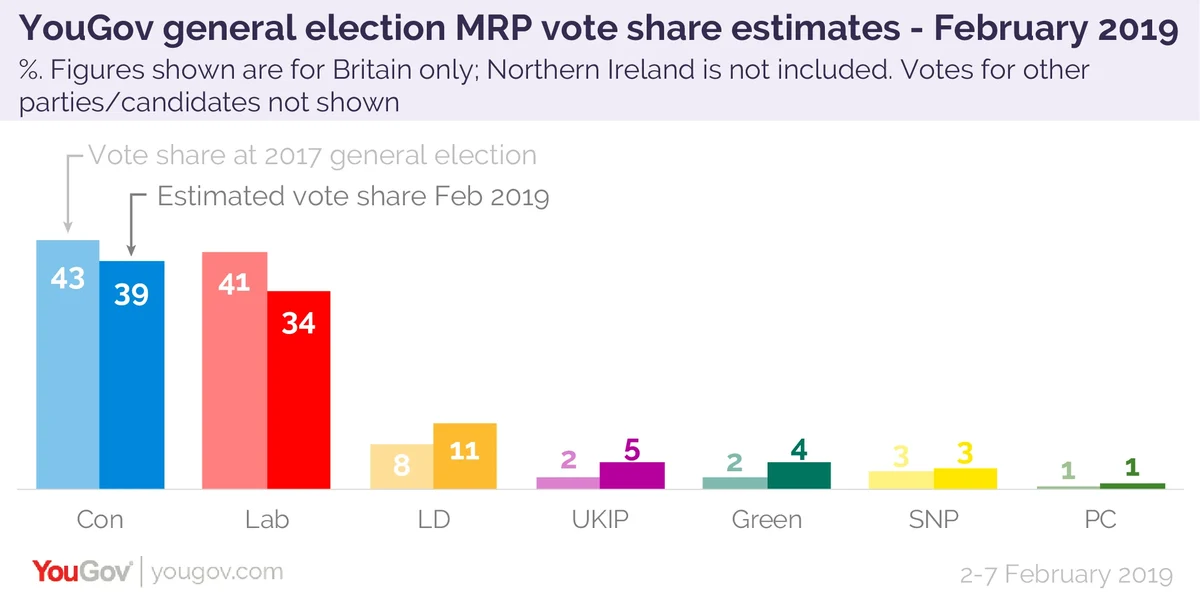

Vote share

In terms of vote share the two main parties see sizeable slumps. The Tories shed four percentage points, falling from their 43% figure in 2017 to 39%. Labour meanwhile lose almost seven percentage points, going from 41% to 34%.

(Please note that these figures apply only to British constituencies, and so would be slightly lower once votes from Northern Ireland were taken into consideration).

The smaller parties appear to be the main beneficiaries, although part of this increase is because the model allowed respondents to support UKIP and the Greens in all constituencies compared to the 2017 election when the parties only put up candidates in some seats. The Liberal Democrats would find themselves netting 11% of votes cast, compared to 8% at the last general election. Likewise UKIP would experience an increase from 2% to 5% and the Greens from 2% to 4%.

The Scottish and Welsh nationalists meanwhile see their vote shares remain essentially static.

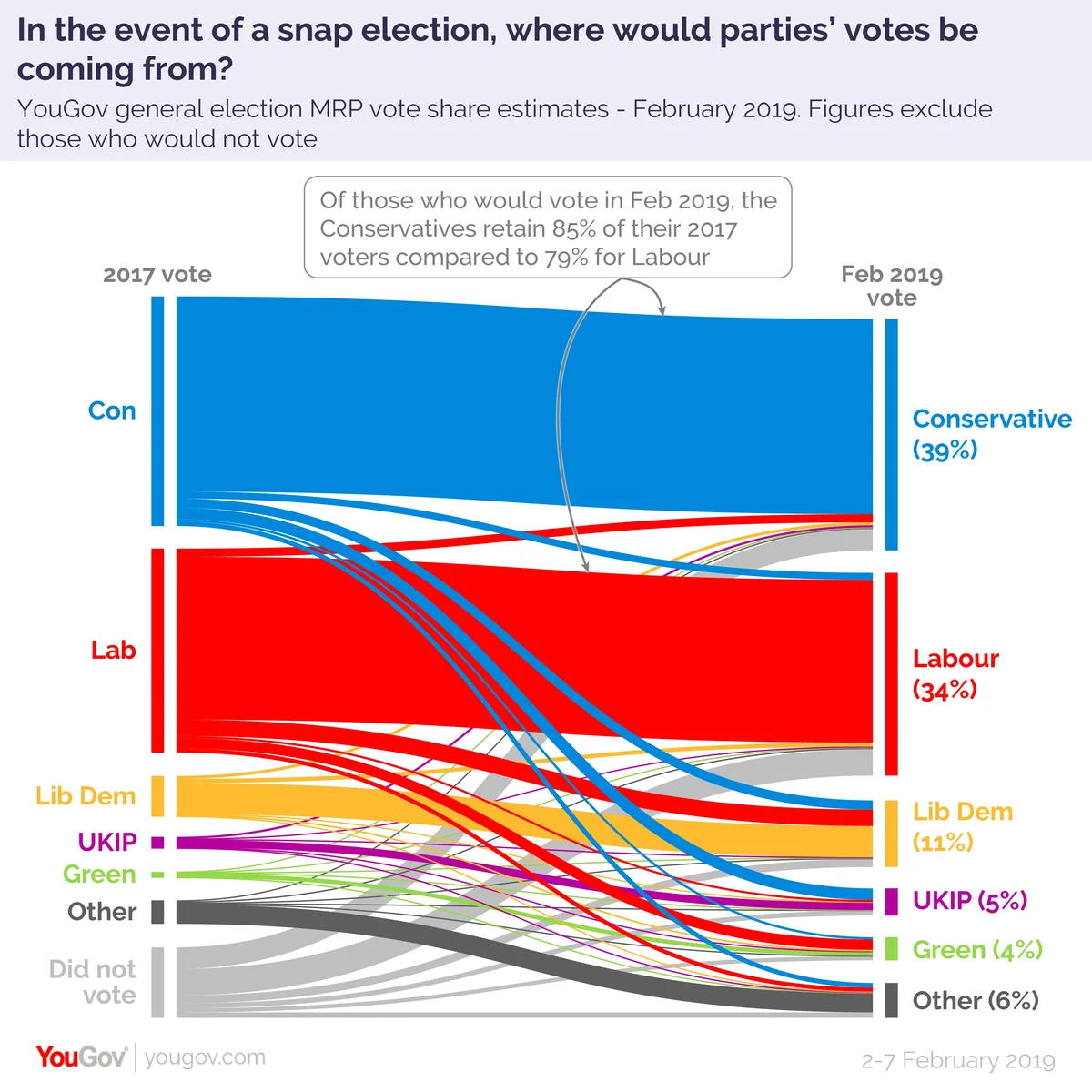

Voters switching parties

Among those who voted for each party in 2017 and would cast their ballot again, the Conservatives retain 85% of their previous voters compared to 79% for Labour.

Most of those who are defecting from Labour are moving to the Lib Dems (8% of those who voted Labour at the last election) or the Greens (5%). Meanwhile many of those who are moving from the Conservatives are going to UKIP (5% of all those who backed the party in 2017) with a smaller number going to the Lib Dems (4%).

Why aren’t the Tories gaining more seats?

Given that Labour are losing a lot more votes than the Conservatives, these vote shares would represent a swing to the Tories of 1.4%. If we were to apply that swing uniformly across all constituencies the Conservatives would gain 16 seats directly from Labour, and end up with a majority of 10.

However the model predicts that as things currently stand they would only manage to gain six of these crucial target seats. The main reason for this is a phenomena sometimes referred to as the “sophomore surge”, where first time incumbent MPs get a slightly higher voter share than would otherwise be expected.

This has been a fairly consistent theme in election results for the past 35 years, most notably in 2001 when there was a 2% swing against Labour nationally but the Tories only managed to pick up four seats.

Many Conservatives target seats are in constituencies Labour first gained in 2017, so they will have to battle against this incumbency boost. On average, in the 28 seats that Labour gained from the Conservatives in the last election, the model is currently showing there would be a small swing to Labour rather than the national swing against.

Further details of the results can be found here

Photo: Getty