“Authoritarian populism” is an emerging force among voters across Europe and could be the defining political phenomenon of the next decade

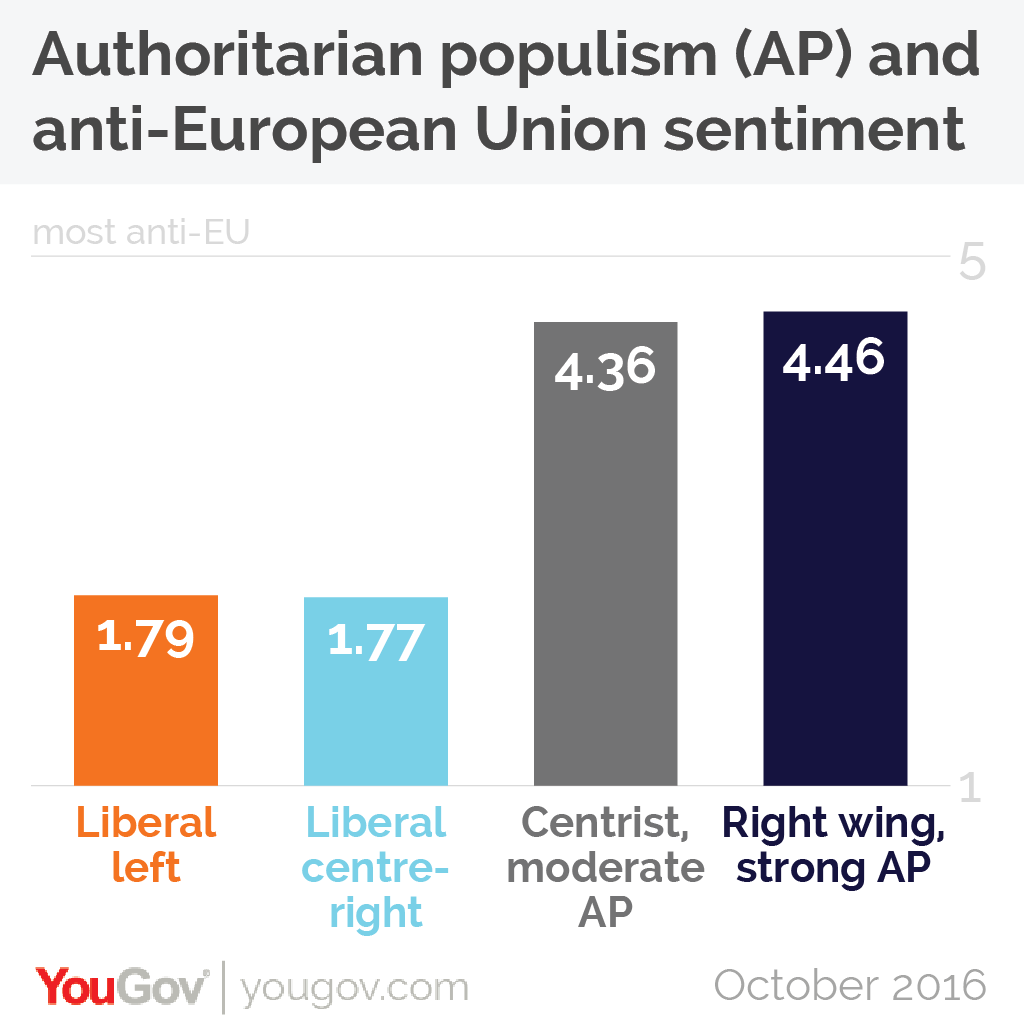

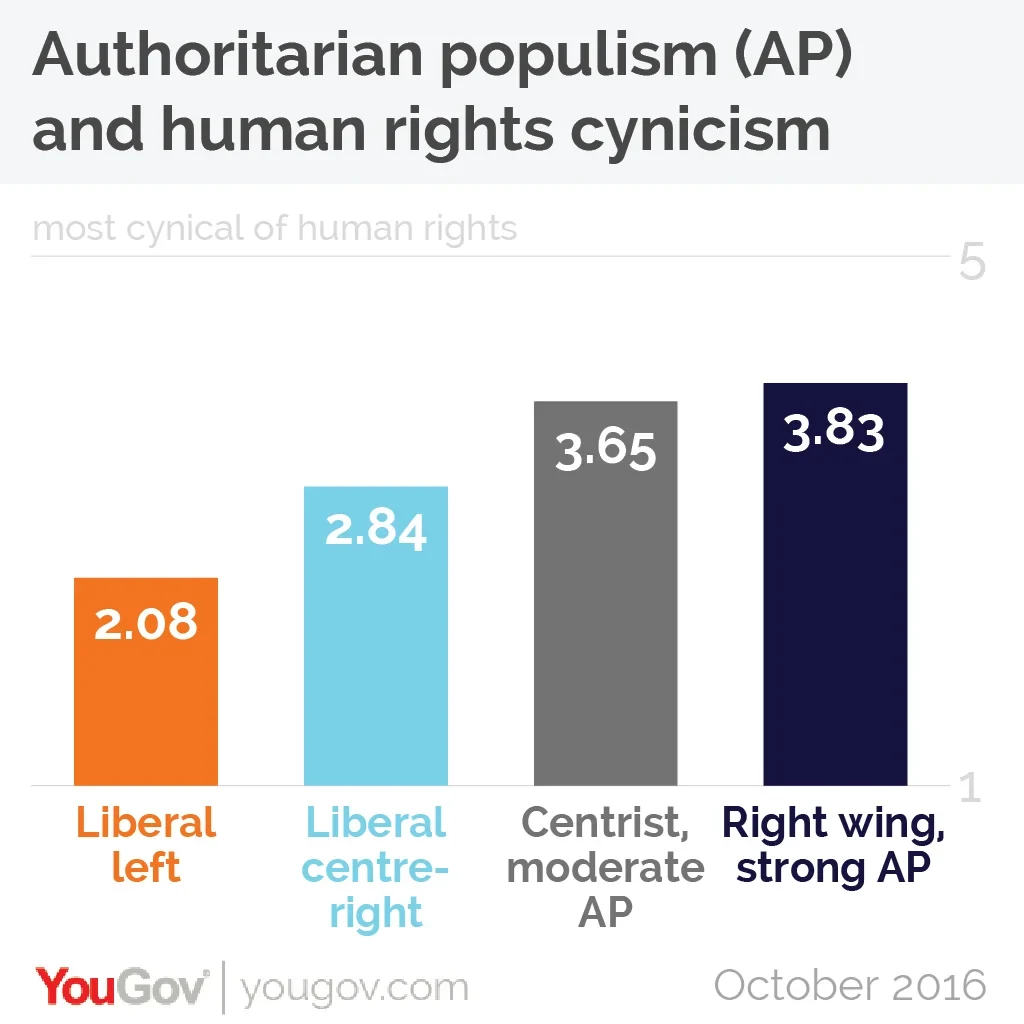

Back in the 1980s, the use of a new academic term became common among some political scientists when describing the politics of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher: “authoritarian populism” (AP). This term was based on the theory that they and their supporters shared a core set of attitudes: cynicism over human rights, anti-immigration, an anti-EU position in Britain, and favouring a strong emphasis on defence as part of wider foreign policy.

Reagan and Thatcher were no longer in power by the end of the 1980s, and with successors such as Bill Clinton and Tony Blair practicing a different style of politics, the term moved to the fringes. The past few years, however, have seen the return of populism to forefront of politics, heralded by parties like UKIP in the UK, the AfD in Germany, the Front National in France – and, of course, Donald Trump in the USA.

In response, some have begun to suggest how politics may now be far more complicated than simply the old “left vs right” categorisation, and instead we should now be talking about, for example, “authoritarian populists vs the elites” or the “establishment vs everyone else”.

With this in mind, YouGov worked with Britain’s Regius Professor of Political Science, David Sanders from the University of Essex to conduct a study across twelve European countries to attempt to quantify the layout of the political landscape from this new perspective.

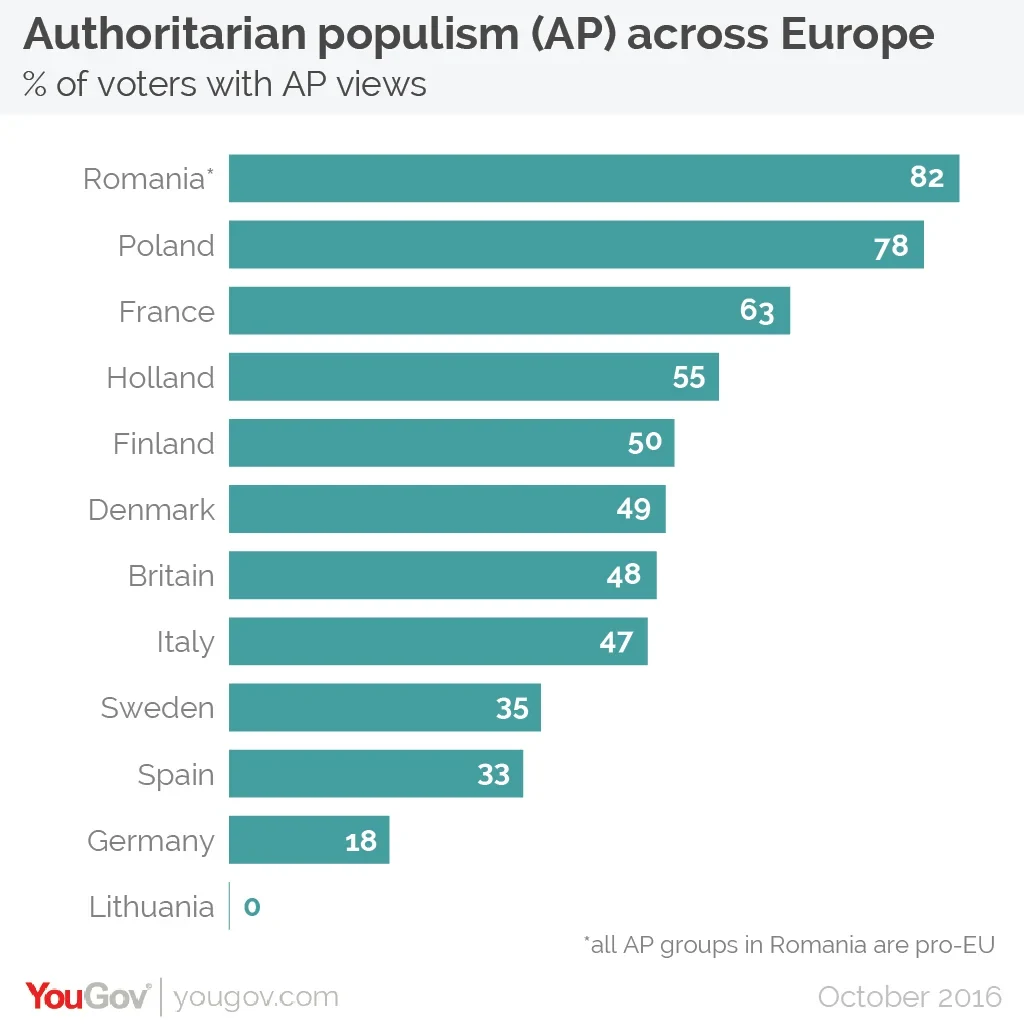

The results may well be cause for concern for politicians in mainstream established parties across the continent. The study has revealed that in eight of the twelve countries, almost half of voters – if not more – hold authoritarian populist views.

This implications for electoral success are potentially enormous. Whilst in each of the twelve countries some variation of the “liberal left” currently constitutes the largest single political bloc, in seven countries the combined AP voter groups represent a greater potential electoral force. Should a politician or party be able to find a way to unite significant numbers of AP voters under their banner, they will be able to issue a serious challenge to the established political order.

The challenge AP poses to the liberal consensus is different in each country. In the UK it could shape the type of Brexit the country pursues. France and Germany have general elections next year and France in particular has a high proportion of voters with AP sentiment. If a candidate there can unite this group behind them it could have serious implications for not just France but Europe as a whole.

Even if politicians are not able to leverage the support of AP voters in such a way as to win power for themselves, it is clear that the pressure exerted by the mass of voters with AP views is significant enough to have an influence on the course of countries across the continent for the near future. What concessions authoritarian populist parties could win from more established political parties remains to be seen, but they could be hugely significant.

Ultimately, there is a very real chance that the rise of authoritarian populism could be the defining political phenomenon of the next decade, and not just in Europe, but across developed democracies.

Authoritarian populism in Britain - the four tribes of British politics

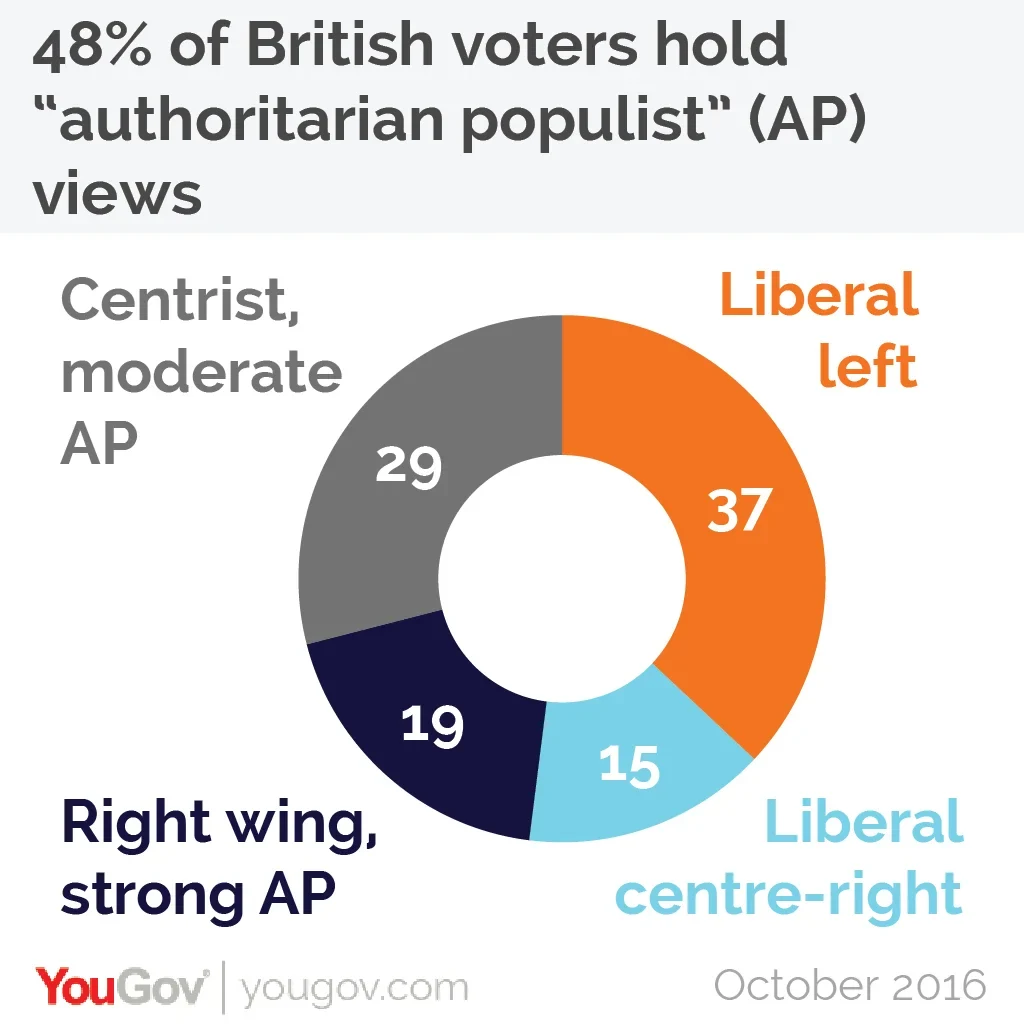

In Britain, almost half of voters (48%) hold authoritarian populist views. The data suggests there are four distinct tribes of British voters – two of which hold authoritarian populist views and two which have a liberal outlook.

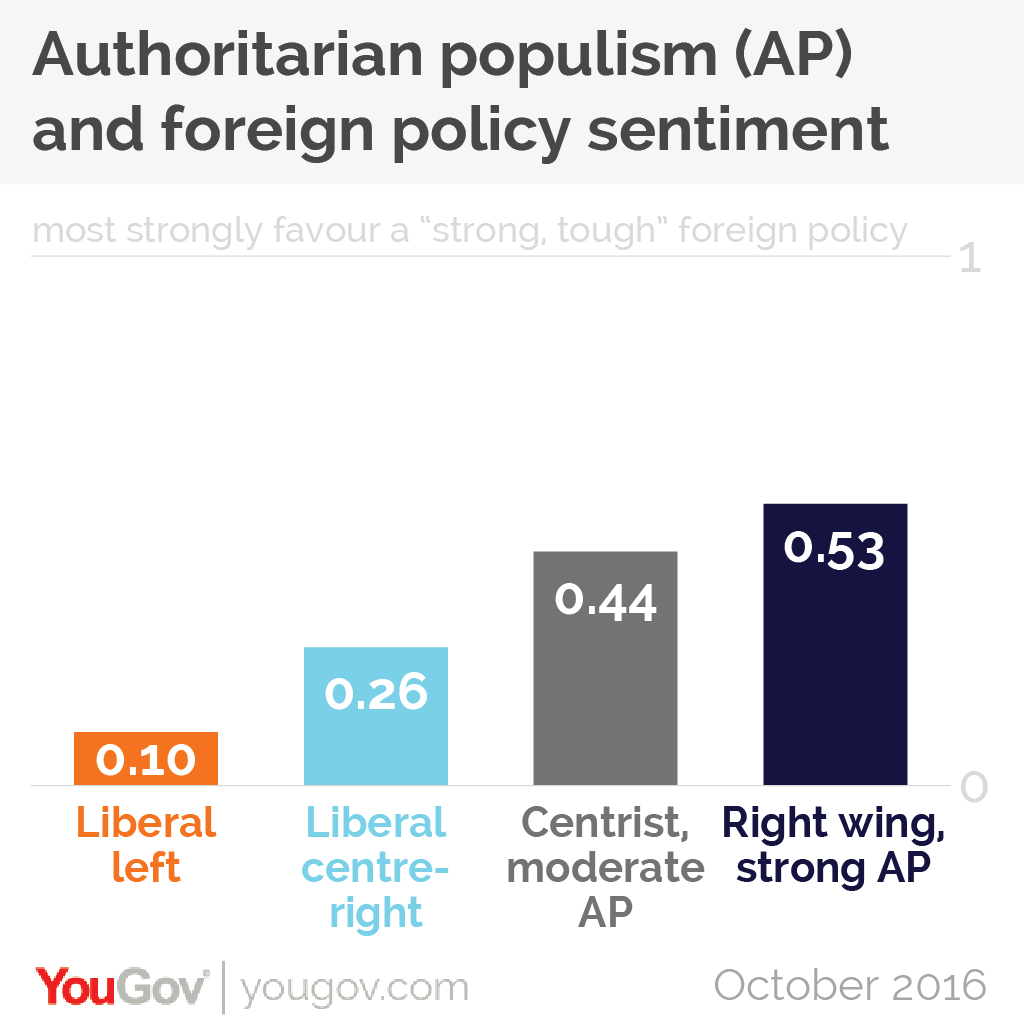

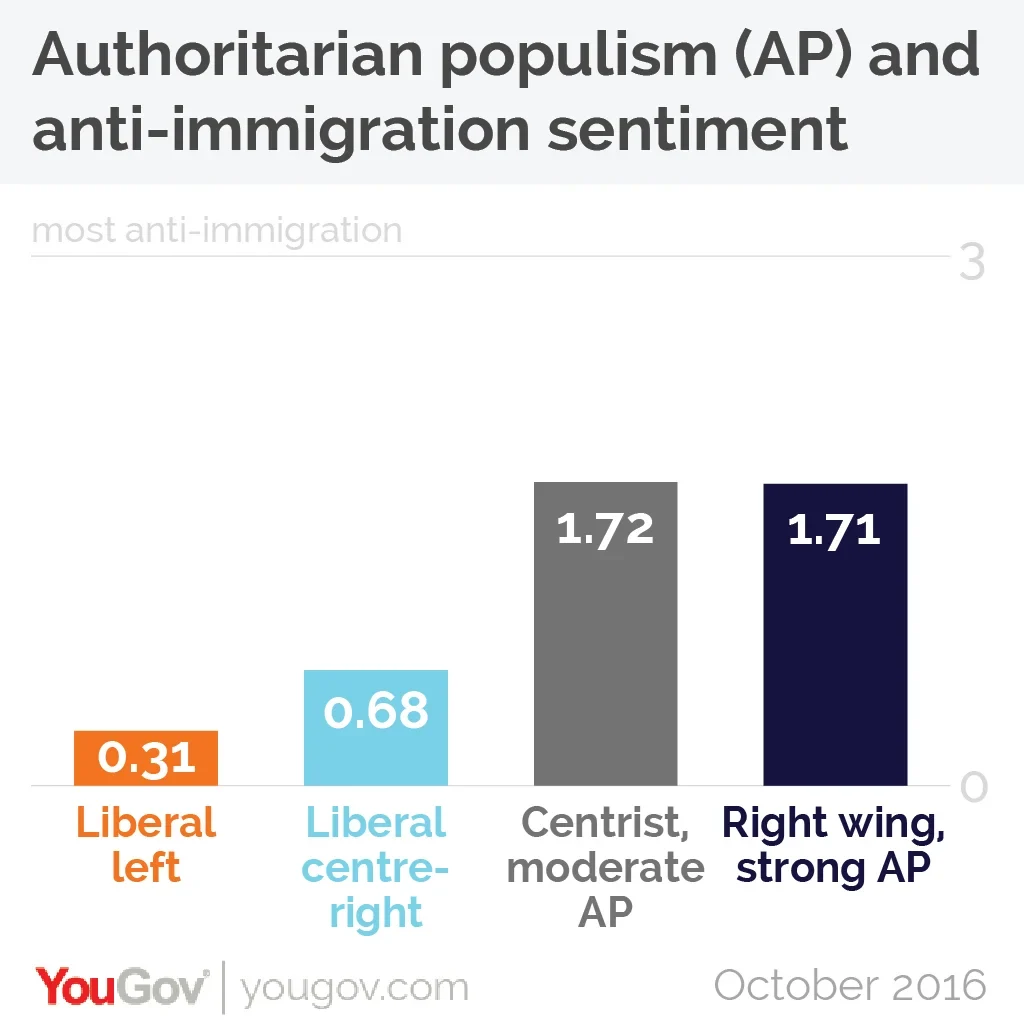

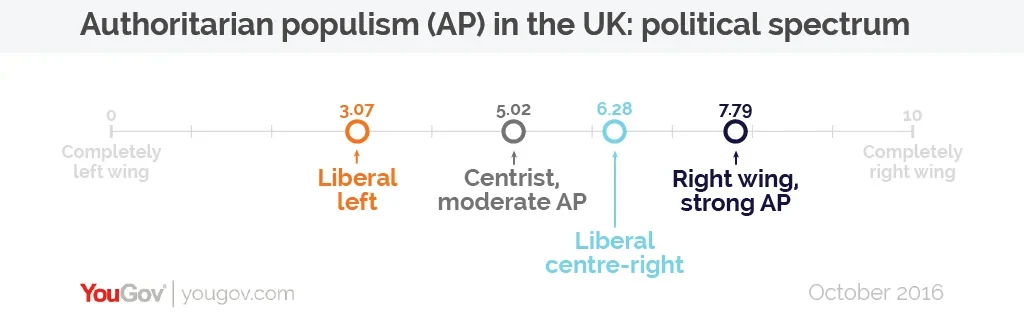

The largest group are the liberal left, constituting about 37% of British voters. This bloc is the least likely to want a strong and tough foreign policy, the least critical of human rights laws and the most pro-immigration. They are also far more left wing than the other groups. On the left/right spectrum, where 0 represents very left and 10 represents very right, they score themselves at about 3.

The other non-AP bloc is the liberal centre-right. They are the smallest of the four groups, with about 15% of British voters falling into this category. They are ever so slightly more pro-EU than the liberal internationalist pro-EU left, but their views are more pronounced in the other three categories. On the left-right scale, they come in at around a 6.

The two AP groups are the centrist, moderate AP, making up 29% of British voters, and the right wing, strong AP, making up the final 19%. Both of these blocs are equally anti-immigration, whilst the right wing, strong AP holds stronger views across the rest of the three categories. As the names would indicate, the AP centrists score about 5 on the left/right scale, whereas the right wing, strong AP are approaching an 8.

Age and AP

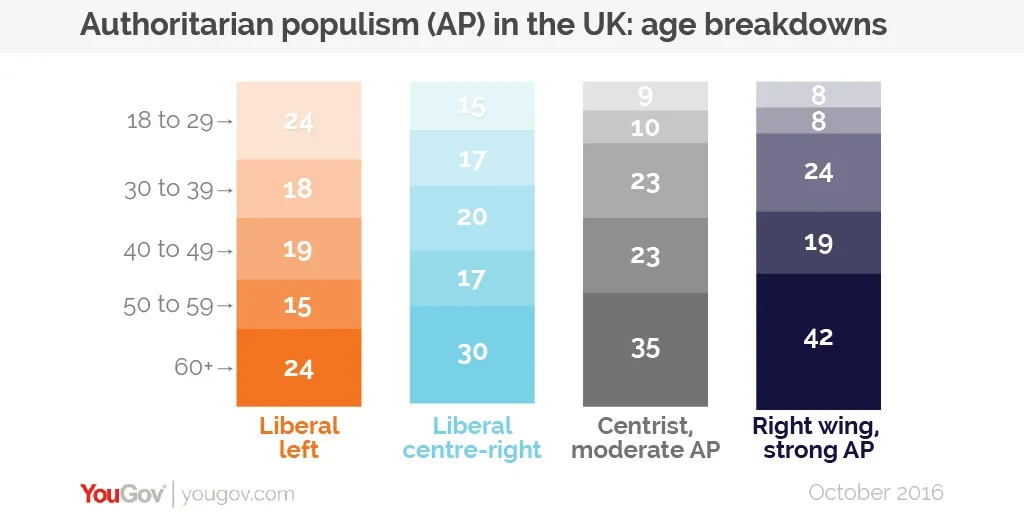

The two liberal blocs have a younger make up than the AP groups. Nearly a quarter (24%) of people in the liberal left are younger than 30 – about three times as many as in the centrist, moderate AP (9%) or right wing, strong AP (8%).

At the other end of the spectrum, a full 42% of the right wing, strong AP are 60 years old or older, as well as 35% of the centrist, moderate AP; by contrast, just 24% of the liberal left and 30% of the liberal centre right fall into this age bracket.

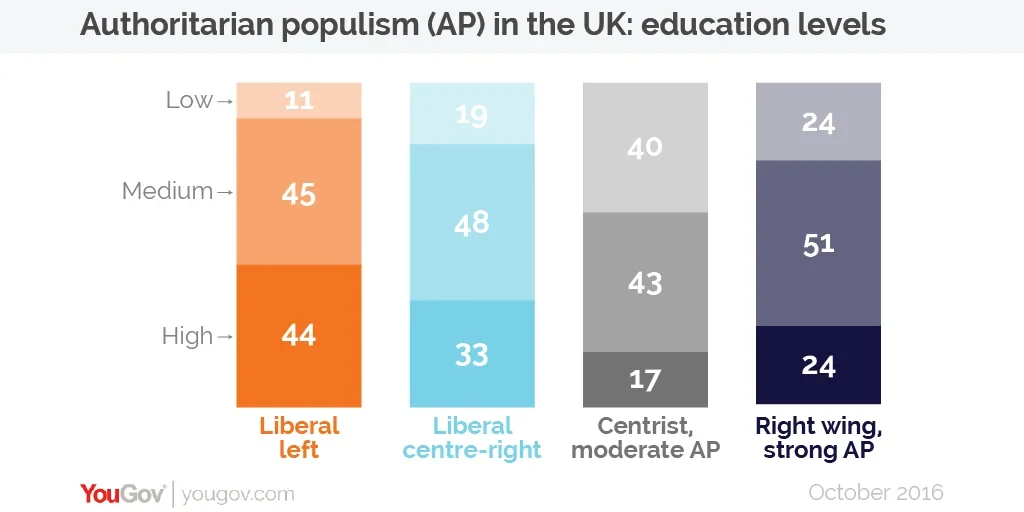

Education divisions

Those with authoritarian populist views tend to be less well-educated than people from the two liberal groups. Four in ten of those in the centrist, moderate AP bloc have a low level of education (qualifications no higher than GCSE or equivalent), as well as a quarter (24%) of those in the right wing, strong AP group.

This is in contrast to the liberal blocs. Over four in ten (44%) of those in the liberal left group have a high level of education (degree level qualified or above), as do a third of people in the liberal centre-right group. By contrast, only a quarter (24%) of people in the right wing, strong AP have a high level or education, and just 17% of people in the centrist, moderate AP.

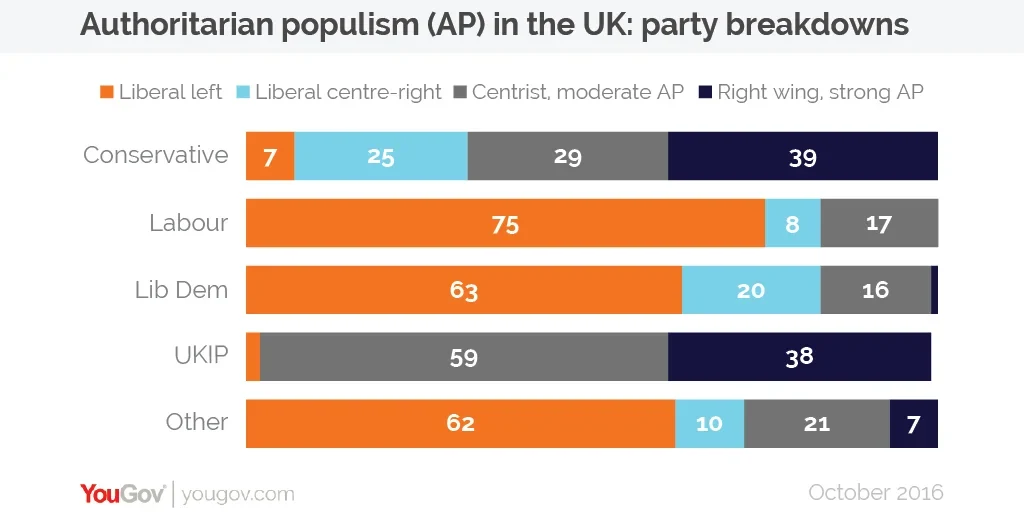

AP support among British parties

AP voters make up a huge proportion of the UK’s two parties of the right: the Conservatives and UKIP. Fully 97% of UKIP voters hold AP views, with 59% being considered centrist, moderate AP and the other 38% right wing, strong AP. While the Conservative party is composed of an almost identical proportion of right wing, strong AP voters as UKIP – 39% - they have far fewer centrist, moderate AP voters (29%) and far more Liberal centre-right (25%).

Britain’s two left main left wing political parties, by contrast, have far fewer AP voters. About 17% of Labour voters are considered centrist, moderate AP, as well as 16% of Liberal Democrat voters. Just 1% of Lib Dems are right wing, strong AP, and there are fewer still in the Labour party.

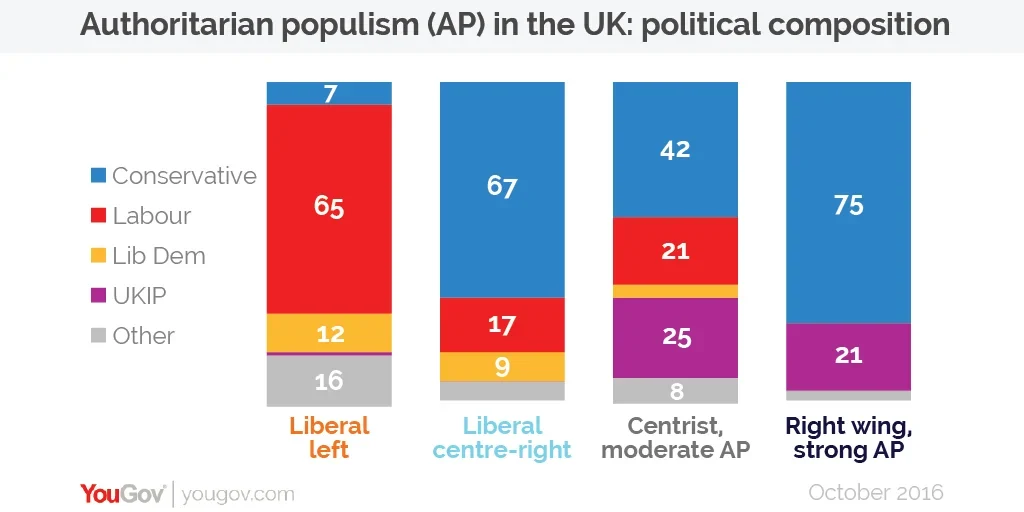

Of course, the parties’ voter bases are of vastly different sizes. Looking at Britain’s political tribes from a different angle shows two – the right wing, strong AP and the liberal centre-right – are dominated by Conservative voters. Three quarters of the right wing, strong AP voters in the UK are Conservatives, with a further 21% being UKIP voters.

The centrist, moderate AP is a much more mixed group, although again the Conservatives are the largest component with 42%. The bulk of the rest of the centrist, moderate AP comes from UKIP voters (25%) and Labour voters (21%), with a dash of Lib Dem and other voters rounding the group off.

Authoritarian populism in Europe

Whilst the rise of authoritarian populist sentiment in Britain is obviously an important factor in the future direction the country might take, so too might the rise of authoritarian populism on the continent have a big impact on Britain’s future.

The most obvious regards Britain’s relations with the European Union now that it has voted to leave. Amongst the majority of countries, AP sentiment is correlated with anti-EU views (but not all – in Romania event though all voter groups hold AP views, they are also all pro-EU). There is a real danger for Britain that, in seeking to demonstrate to their domestic AP voters that life outside the EU is an unappealing prospect, EU leaders will ensure that Britain gets a poor Brexit deal.

An alternative outcome is that the rise of authoritarian populism captures one or more European governments and ends up causing the demise of the EU itself. All work on Brexit negotiations, if Article 50 has even been triggered by this point, will subsequently become redundant and Britain – and the wider world – will be plunged into uncertainty.

Nowhere is this danger more obvious than in France. In France, as with the UK, the liberal left constitutes 37% of voters. Unlike in Britain, however, the entirety of the rest of the voting population – 63% of voters – hold authoritarian populist views. With a presidential election coming in early 2017, a lot will rest on how these AP voters behave in the first round of voting.

Should the AP vote skew more towards the far right National Front party’s candidate Marine Le Pen, this could mean France’s centre-right party, The Republicans, fail to get enough votes to make the second-round, giving Le Pen a real chance of winning the presidency.

With one of the EU’s two most integral members now led by a far right anti-EU president, a Le Pen victory could very well lead to dramatic consequences for the European Union.

The events of 2016 suggest that the rise authoritarian populism is already shaping the future of Europe. Understanding what has caused this rise and how major parties to engage with AP voters will be a major aspect of the elections in 2017.

Methodological Note

To identify the Authoritarian Populist groupings Exploratory Factor Analysis was used on a series of variables associated with the theoretical foundations of Authoritarian Populism (anti-human rights, anti-EU, anti-immigrant, pro-strong foreign policy) with an alpha scale check that gives you a reliability coefficient.

Inevitably, the interpretation and grouping of results of this type is as much an art as a science, so the results involve the analyst’s own judgement. Unsurprisingly, the analysis by country produces slightly different patterns in each country, demonstrating the varying political landscapes.

The YouGov 12-Nation Authoritarian Populism Study was conducted in September 2016 and forms part of an ongoing body of work on authoritarian populism. Full results will be published soon. This survey has been produced for the annual YouGov-Cambridge Forum, a joint conference held by YouGov and the Cambridge Department of Politics and International Studies.

The sample sizes from each country are as follows: Britain 1,711; France 1,002; Germany, 1,046; Sweden, 1,008; Denmark, 1,008; Finland, 1,006; Poland, 1,016; Italy, 1,012; Spain, 1,010; Romania, 1,012; Lithuania, 1,015; Holland, 1,015.