The question is obvious, simple and urgent. Would Labour do better under a different leader? Unfortunately the answer is both complex and uncertain.

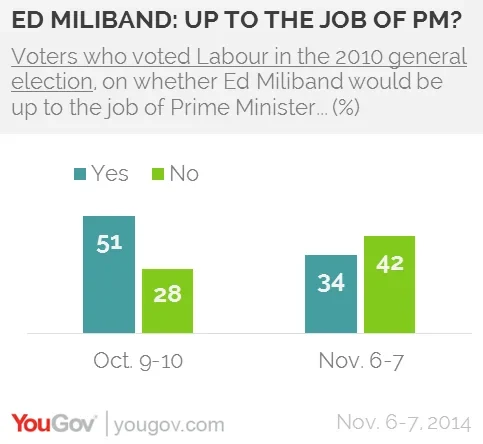

Let’s start with the truth that Ed Miliband himself cannot deny. His ratings are terrible. According to YouGov’s latest poll for the Sunday Times, just 18% of the public think he is up to the job of Prime Minister; 64% do not. That’s not the worst of it. Among people who voted Labour in 2010, only 34% now think he is up to the job – a marked fall from his 51% rating just one month ago. 42% of these voters say he is NOT up to the job, a big jump from 28% in early October.

Other YouGov polls tell a similar story, and help to explain why Labour’s lead, 14% at its mid-term peak two years ago, has now evaporated. Compared with November 2012, fewer people see Labour’s leader as strong, honest and decisive. He used to score reasonably well as someone who is ‘in touch with ordinary people’. No longer.

So: has the time come for Miliband to go?

Were Labour miles behind the Conservatives and heading for inevitable defeat, the answer would be clear. There is nothing to lose; let’s try someone else. But there are two big reasons why things aren’t that simple.

The first is that, even now, defeat is not inevitable. Currently Labour and the Conservatives are level-pegging on 33%. Miliband is unpopular, but so is the coalition. On those figures, Labour would probably win more seats than the Tories (although the impact of the Liberal Democrats, UKIP and SNP add a huge amount of uncertainty to any attempt to convert votes into seats).

In other words, there is much to lose if Labour botches a change of leadership.

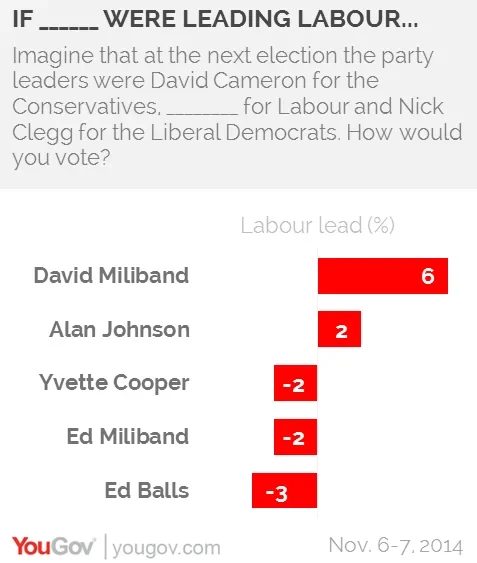

Secondly, our Sunday Times poll finds that any no other leading Labour MP would make much difference. Alan Johnson would boost Labour’s support a bit, but he insists he’s not interested. Ed Balls and Yvette Cooper would do as badly as Miliband. The only man who would make a material difference is David Miliband, and he is in New York.

This puts Labour in a very different position from the Conservatives in 1990.That autumn, during the dying days of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, polls found that her departure would add at least six percentage points to Tory support. Voters hated the poll tax, which had been introduced a few months earlier, and they increasingly hated her strident manner. Her party was badly divided over Europe. Voters wanted not just a different leader, they wanted different policies and a more consensual Prime Minister. When John Major replaced her, Labour lost its double-digit lead and the Conservatives moved ahead.

The difference between then and now goes beyond polling figures. Labour is suffering no great division over policy or doctrine. Indeed, even Miliband’s critics credit him with holding it together far better than previous leaders did on the three previous post-war occasions when it lost power: 1951, 1970 and 1979. Paradoxically, that’s part of the problem. Division has been lacking, but so has the kind of original thinking and political ferment that has helped past oppositions to revive their fortunes and reconnect with voters.

What about the alternative Conservative model of leadership replacement: the way Michael Howard replaced Iain Duncan Smith in 2003. The execution was swift, the succession consensual. Nobody challenged Howard for the leadership. The drama was over in hours.

The trouble with that example is that the change failed to boost Tory fortunes. In four YouGov surveys in the weeks before Duncan Smith’s dismissal, Labour and the Conservatives were level pegging – as they are today. In our four surveys in the weeks following Howard’s arrival, Labour and the Conservatives were still level pegging. Eighteen months later, the Tories lost badly, winning fewer than 200 seats. It turned out that what voters disliked was the party, not just its leader.

That is Labour’s problem today. It is still blamed more than the coalition for Britain’s continuing economic problems. It is trusted far less than the Conservatives to tackled the Government’s deficit. Too few people expect a Labour government to improve their lives. Replacing Ed Miliband with a new leader would work if, and only if, the new leader were able to persuade voters to look more kindly on Labour’s past and to have more faith in the party’s future.

This means reshaping social democracy for an era in which its traditional solution to most problems – spending more money – is no longer available. This is a huge challenge, and a far greater task than finding someone who looks less like Wallace, can remember his lines and knows how to eat a bacon sandwich.

I have heard, seen and read nothing in the past few days to suggest that any feasible successor to Miliband will do this – or that those MPs wanting Miliband’s head are demanding anything so ambitious. The debate is about personal style, not the future of progressive politics.

So, my answer to the question I posed at the start of the blog is: it’s the wrong question. Miliband is certainly unpopular, and his weaknesses have contributed to his plight; but the bigger weaknesses belong to the party as a whole. Voter threw Labour out four years ago and it has given them no good reason to change their minds. The mayhem of the past few days has been a giant displacement activity of benefit only to Labour’s opponents.

I see you are still pressing me for answer. Would Labour do better under a different leader? I don’t know. It depends – not just who s/he is, but what s/he does. Surveys at this stage cannot predict how events would play out, or how voters would react to them. But unless the party offers us not just a new leader, but a new form of social democracy suited to tough times, my guess is that getting rid of Ed Miliband would make little difference.