YouGov has repeated some questions we asked in May 2009. Our results challenge five myths about Ukip's performance

In the short run, Ukip is plainly on a roll. It won last month’s European Parliament election, and might win this week’s Newark by-election. Although Nigel Farage’s rating has slipped in the past few weeks, he still enjoys higher ratings than David Cameron, Ed Miliband or Nick Clegg. His style of campaigning appeals to millions of voters.

And yet… a different picture emerges when we look at how public opinion has evolved since the last European parliament elections in 2009.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

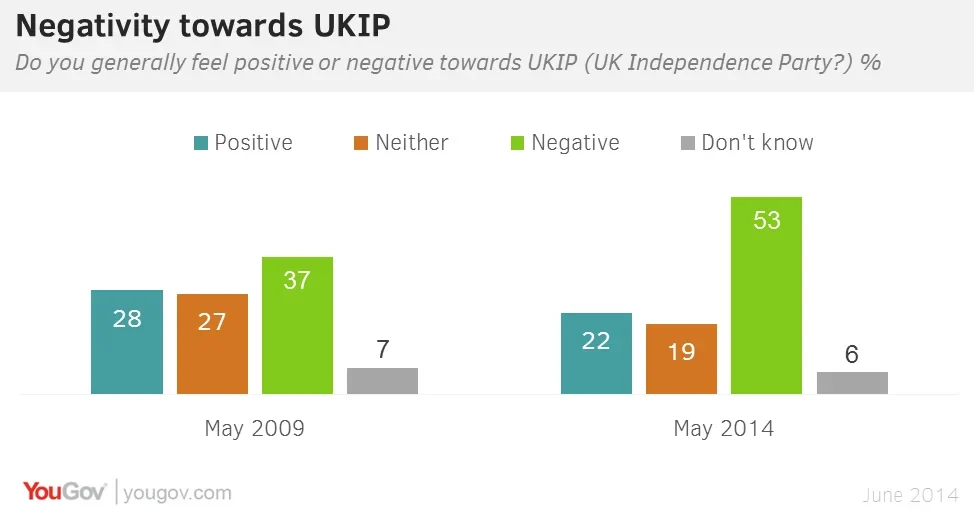

Myth One: Ukip is now more popular than ever before.

True, Ukip’s vote share is up 11 points, from 16.5% in 2009 to 27.5% this time. However, the number of people liking the party has actually fallen:

More detailed analysis of the data shows that in 2009, Ukip secured the support of fewer than half the voters who felt positively about it. The rest voted Conservative or BNP – or, in smaller numbers, Labour, Green or Liberal Democrat. Last month, Ukip harvested almost three-quarters of those who felt positive about it. Ukip benefited from the collapse in BNP support and the greater willingness of unhappy Tories to lend their votes to Ukip this time round.How can this be? How can Ukip win 27% of the vote and yet be regarded positively by only 22% of the electorate? Part of the answer is that only one elector in three turned out to vote in the recent election. Ukip won the support of just 9% of the electorate.

Overall, Ukip has not so much won new friends as polarised public opinion. Ukip did better this time at turning diminishing approval into votes, but it also alienated far more of the electorate. Millions more voters now regard Ukip negatively than in 2009, and fewer decline to take sides.

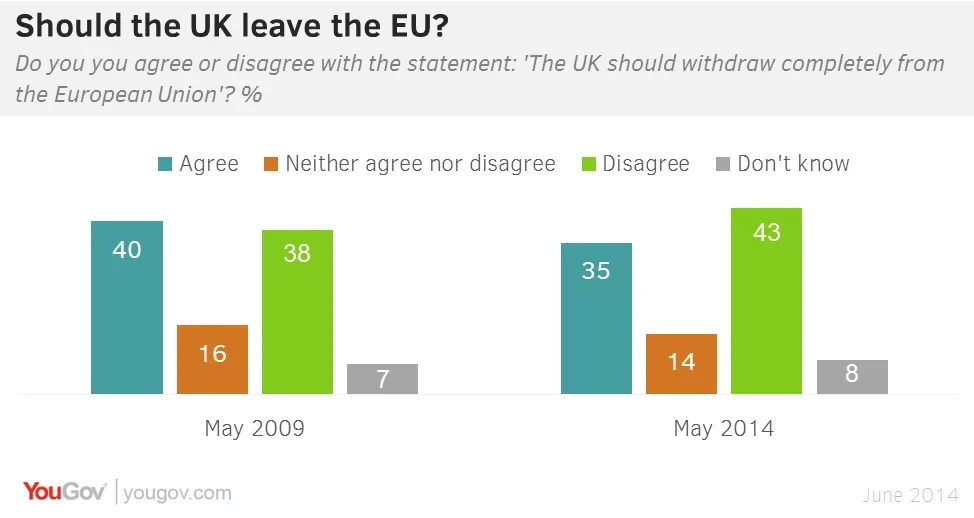

Myth Two: More Britons wish to leave the European Union than in 2009.

The opposite is true. Five years ago we divided narrowly in favour of complete withdrawal from the EU; today, by a modest margin, we prefer to remain a member:

However, we want ‘Brussels’ to do less. Five years ago, 60% of us wanted the EU, rather than individual countries, to decide measures to combat climate change; that figure is now 51%. The proportion wanting the EU to set the rules for international trade is down from 35% to 25%. There is less change in the desire for the EU to decide common policies for immigration, but few people wanted that anyway.Our latest figures are consistent with YouGov’s tracker series on how people would vote in a referendum on whether to leave the EU. Since earlier this year we have found a consistent, modest lead for keeping up our membership.

In short, the centre of gravity of public attitudes seems to be moving towards the Conservative position: a growing public appetite for reducing the powers of the EU, especially on whom we allow to live in Britain, but not for quitting altogether.

As Farage often points out, the only way Britain can decide which immigrants to admit is to leave the EU. Until then we are bound by the principle that EU citizens can live in any of the 28 member states. However, our survey suggests that many people either don’t realise that, or do realise it but regard free movement as a price worth paying. Which leads us to…

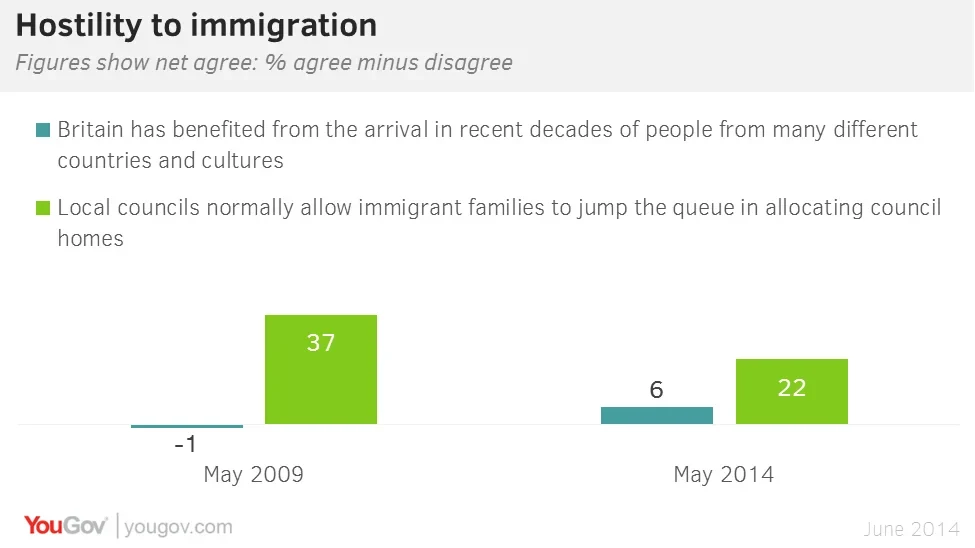

Myth Three: British hostility to immigrants has reached new heights.

We repeated two statements that we tested five years ago, and asked people whether they agreed or disagreed with them. One was a positive view of Britain’s diversity, the other an oft-repeated negative view about access to council housing. Compared with 2009, we are less worried about the impact of immigration on British life:

That’s not to say that voters want immigration to continue at the present rate. YouGov has found repeatedly that most people want it cut substantially. Ukip’s views strike a chord with a great many voters. But on both the statements we tested, hostility to immigration has declined in the past five years.

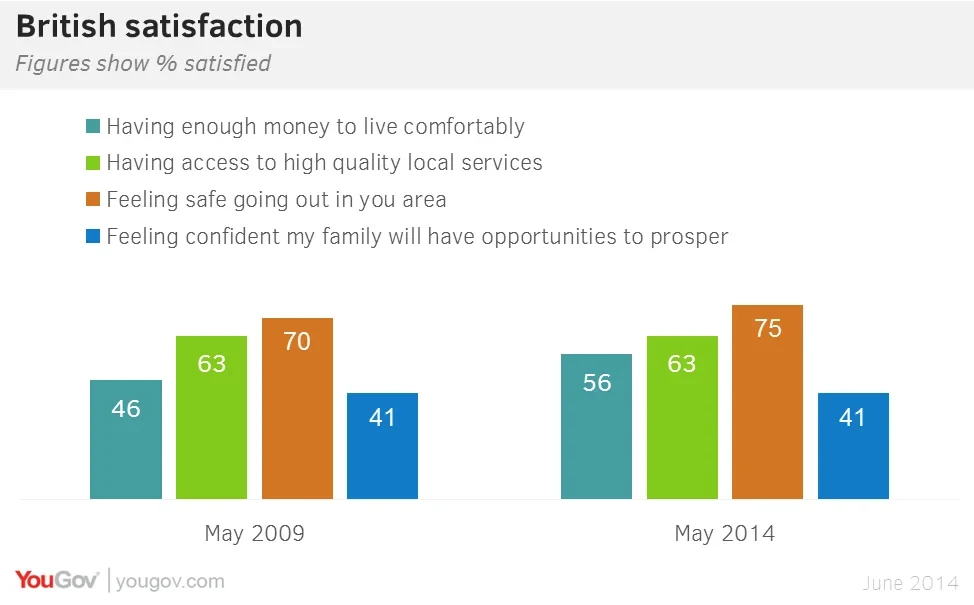

Myth Four: Britons feel worse off and more pessimistic than they did in 2009.

Ukip draws much of its support from two overlapping groups: unhappy Conservatives and older, less well-off white working class men. What unites most of them is dissatisfaction with today’s Britain and pessimism for the future. Yet the electorate as a whole is no gloomier than it was five years ago, and on two of our four measures it is more cheerful:

Even so, it’s striking that the proportion satisfied with ‘having enough money to live comfortably’ is up a full ten points – and that, despite the spending cuts of the past four years, exactly the same, fairly high, number of people feel they have access to high quality public services in their local area. That is plainly good news for the Conservatives.A little thought should leave us unsurprised by these figures. Five years ago, the country was mired in recession. The measures to revive the economy, which started to recover a few months later before stalling again, had not yet started to work. Today, growth seems finally to have resumed.

That still leaves plenty of people who feel left behind, and plenty of votes for Ukip to harvest. But, as a whole, we are slightly less pessimistic than we were.

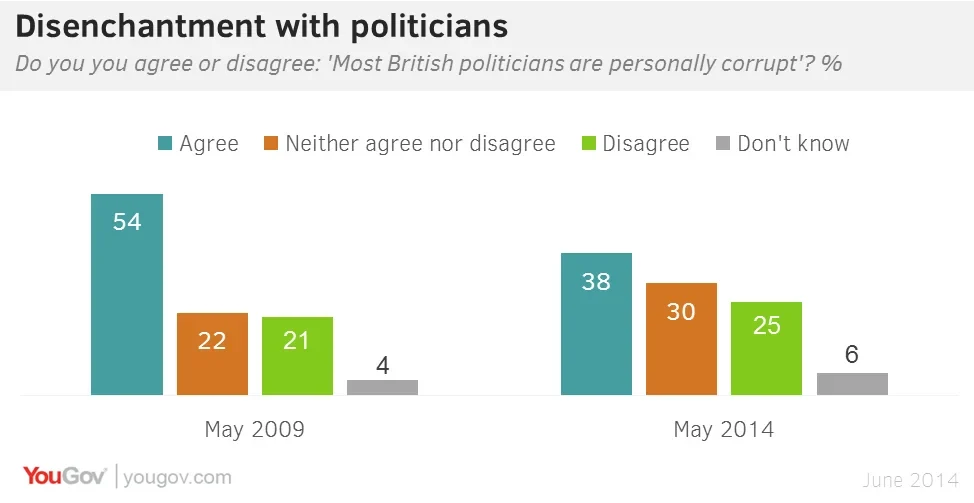

Myth Five: disenchantment with conventional politicians is at record levels.

This is certainly untrue. The 2009 elections took place in the middle of the furore over MPs’ expenses. A majority thought that ‘most British politicians are personally corrupt’. That figure, though still worryingly high, is down significantly:

In particular, Ukip has benefited from three political boosts: the collapse in support for the BNP; the decision of the Liberal Democrats to join the coalition (which left Ukip as the most obvious destination for protest votes); and the fact that the Conservatives are in government, for support for governing parties tends to fall in European Parliament elections, when the opportunity for voters to ‘send a message’ is enhanced by a proportional voting system.Nothing in these figures or this analysis should be taken to belittle the concerns about today’s Britain, or the worries about the economy, immigration or European Union that attract voters to Ukip. Rather, they are evidence that the reasons for Ukip’s surge last month are more complex than they appear at first sight.

This changed political climate helped Ukip and outweighed the social and economic factors that are less favourable to the party today than they were five years ago. Yes, Ukip has exploited a cry of rage against the things that are wrong with Britain today; but that rage is less intense than it was five years ago.

The challenge facing Farage is to sustain his party’s momentum as we approach the very different political context of a general election fought under first-past-the-post. If Britain’s economy continues to grow and its fruits are share more widely, his task will grow harder.

That is why this week’s Newark by-election matters so much. A Ukip victory would eclipse these gradual, underlying shifts in sentiment. Winning its first seat at Westminster, after last month’s nationwide victory, could be a game-changer and make it a permanent feature of British politics. But defeat in Newark could have the opposite effect, not least because it would be the first time in 25 years that the Conservatives have won a by-election while in government . In due course, we might look back on the local and European elections as the dark before dawn for the Tories, and the sun before dusk for Ukip.

Image: Getty