(The original version of this article was published by the Royal United Services Institute here)

Public opinion on paying hostage-takers reflects a broader contradiction between principle and practice.

The recent release of the kidnapped Italian aid worker, Silvia Romano, spurred rumour and speculation about whether her kidnappers had received a ransom. This was only the latest crescendo in a debate that has rumbled more loudly ever since a number of international aid workers and journalists were murdered at the hands of the so-called Islamic State, or “ISIS”, in 2014.

Paying ransoms to terrorist groups for the release of hostages certainly contradicts the letter of international law. Yet a number of governments have chosen that option in recent years, even while ostensibly opposing it. According to new polling on the subject, it seems that public opinion reflects a similar contradiction between principle and practice when it comes to paying ransoms. RUSI recently partnered with YouGov to survey attitudes to the subject in six Western countries, including national samples in the US, France, Sweden, Denmark, Britain, and Germany.

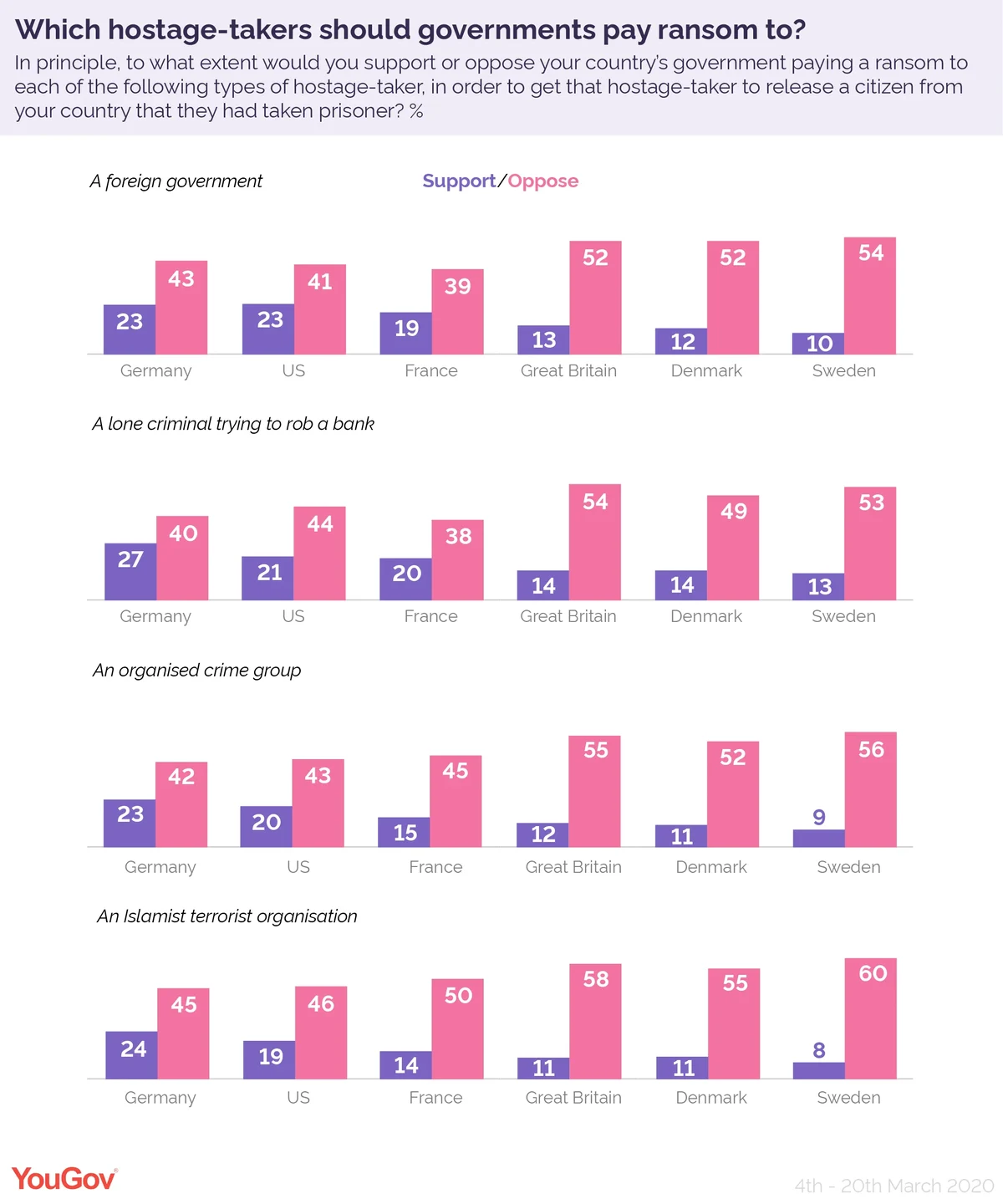

Respondents were asked to what extent they support or oppose their government paying ransoms to various types of hostage-takers in order to secure the release of a kidnapped citizen from their country, including payment to ‘a lone criminal trying to rob a bank’, ‘an Islamist terrorist organisation’, ‘an organised crime group’ (OCG) and ‘a foreign government’.

In each case, the larger portion of people tended to oppose ransom payment, with each sample showing the strongest opposition towards paying an Islamist terrorist organisation. In Britain, for example, 58% of respondents said they oppose paying a ransom to Islamist terrorists in order to secure the release of a British hostage, versus just 11% expressing support. We find similar figures among British respondents for the other scenarios, including 54% oppose versus 14% support for paying a bank robber, 55% oppose versus 12% support for a paying an OCG, and 52% oppose versus 13% support for a paying a foreign government.

This mood is broadly mirrored on the question of legality. Respondents were further asked if paying a ransom to the same categories of hostage-taker should or should not be illegal. In most cases, a clear majority or plurality answered that ransom payment should be ‘illegal’, again with terrorists stirring the strongest response. For instance, 55% of Britons stated that securing the release of a hostage by paying a ransom to an Islamist terrorist organisation ‘should be illegal’, compared with 17% saying the opposite – that it ‘should not be illegal’. By a similar token, the respective split in other country-samples was: 46% versus 23% in the United States; 58% versus 15% in France; 58% versus 14% in Sweden; 46% versus 21% in Denmark; and 53% versus 21% in Germany.

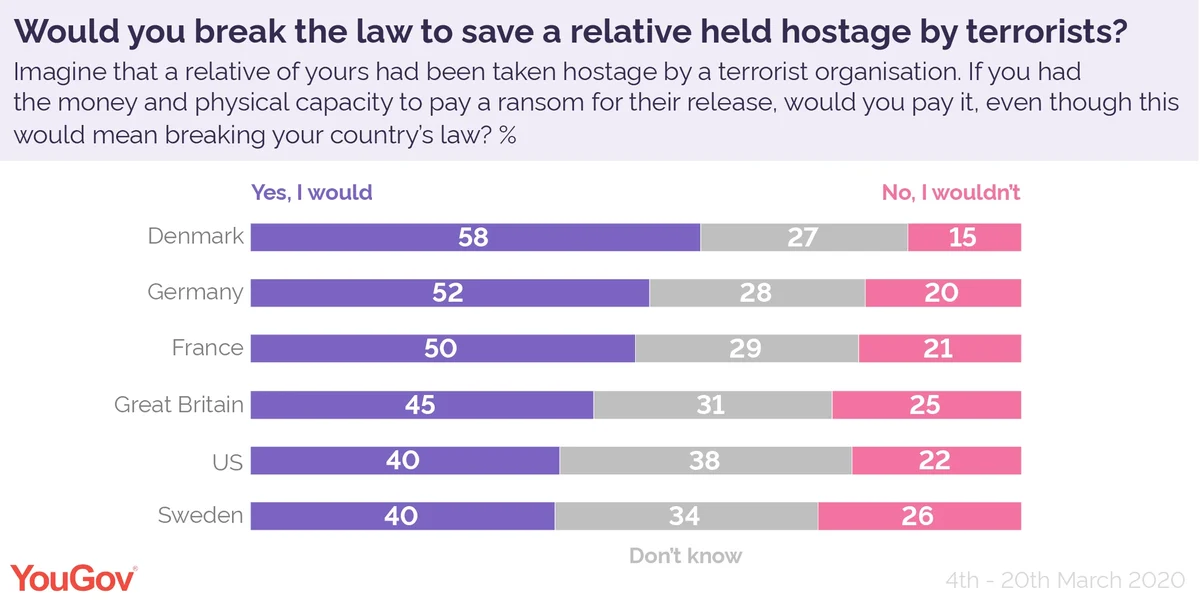

Predictably, however, the general balance of opinion reverses if the issue is personalised. Each sample was also asked if they would pay a ransom for the release of a relative held by an Islamist terrorist organisation, assuming that requisite money and physical capacity were available. In this case, by far the larger portion answers ‘yes I would’, including clear majorities or pluralities in each country. And while positive responses declined by some five to 15 percentage points when respondents were informed that such payments would be illegal, the overall sentiment remains consistent.

So how should governments interpret this contradiction? Aspiring to an ambition of universal non-payment of ransoms is clearly optimal. But official policy arguably needs to catch up with a more complex, modern relationship between rhetoric and reality. It is perhaps for this reason that US debate following the murder of its citizens at the hands of the Islamic State resulted in a more nuanced approach, which duly reaffirmed that Washington would not pay ransoms to terrorist groups, while essentially leaving the private option open, albeit without explicitly sanctioning payment by families. These survey results suggest that other governments could be well served in considering a similar approach.

See results

Methodology: total sample sizes were: US=1,243; France=1,006; Sweden=1,004; Denmark=1,015; Britain =1,695; Germany=2,097. Fieldwork was undertaken between 4–20 March 2020. The surveys were carried out online. For each country sample, results have been weighted and are representative of the adult population aged 18+.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

BANNER IMAGE: Silvia Romano was taken hostage in Kenya in 2018. She is pictured returning to her home in Italy on 11 May 2020. Courtesy of Mondadori Portfolio/SIPA USA/PA Images.

Graphics by Eir Nolsoe, YouGov Data Journalist