On average, women – and young women in particular – are more likely to report feeling stressed and sad

Since July 2019, YouGov have been tracking Britain’s mood every week – asking the public which of a selection of moods best describes how they’ve felt over the past week.

It has tracked the ebbs and flows of national emotion – from the annual bump in happiness at Christmas, through the surges in sadness after the outbreak of war in Ukraine and Queen Elizabeth II’s death, to the boredom and loneliness of the Covid lockdowns.

The announcement of the first national lockdown, around 23 March 2020, was when we see the extremes for many emotions – it was the low point of happiness (25%) and contentedness (13%) over the last five years, but the high point in people feeling stressed (50%) and scared (36%). As later lockdowns wore on, stress receded, but the tedium rose. In February 2021, during the third nationwide lockdown, the country reached new levels of boredom (40%) and loneliness (22%), with this giving way to a peak in optimism (27%) in early March as the lockdown eased and the vaccine was rolled out.

2022 sparked a rollercoaster year in terms of sadness. The outbreak of war in Ukraine led to 36% of Britons describing their mood as sad in March 2022, the highest over the last five years. But it was just months later, in mid-July, that national sadness fell to its lowest point on the tracker – less than one in five (19%) saying they were sad during a heatwave and the Women’s Euros. Sadness surged again (to 34%) following the Queen’s death in September, with optimism falling to its lowest point in the last five years (13%) during Liz Truss’s last week as prime minister.

But what can the tracker tell us beyond this series of snapshots of the national mood? By taking the last five years’ data on average, we can identify some key trends in terms of what Britons tend to feel and who tends to feel what.

Overall, the most common emotion on any given week has typically been happiness – which has been averaged at 45% over the past five years and has been the top feeling on 80% of weeks. Unfortunately, we aren’t all feeling happy all of the time, with stressed and frustrated the next two most common moods, averaging at 40% and 35% respectively.

At any one time, we can expect about a quarter of Britons to be content (26%) or sad (25%), with 22% typically bored and one in six (17%) being lonely on average. Only one in five Brits (20%) typically feel particularly optimistic, with only one in ten of us (10%) describing ourselves as inspired in any given week.

Younger people are moodier, though not necessarily in that way

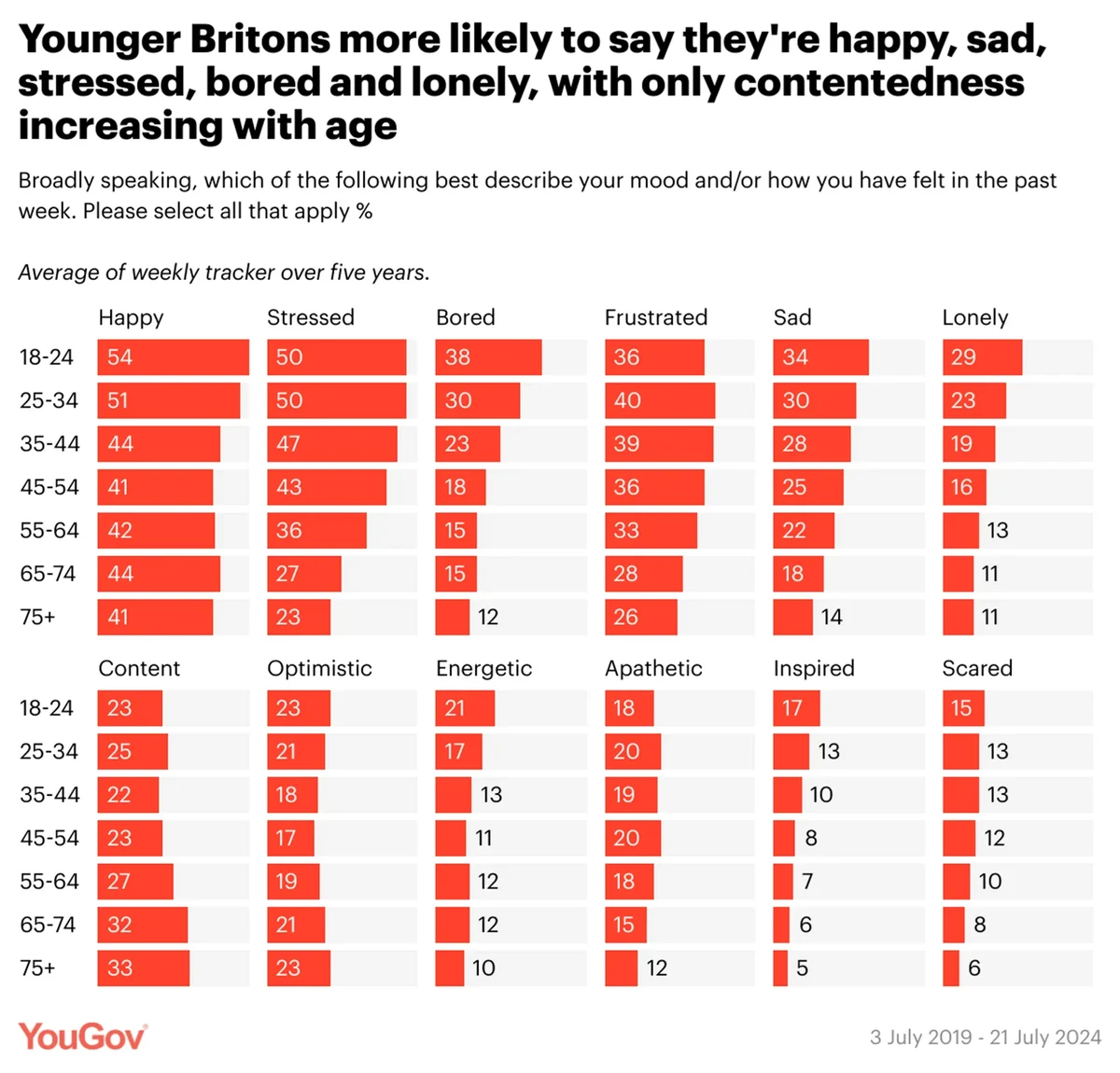

Age has been one of the main variations across the mood tracker, with younger people having been more likely to say they hold most of the listed moods over the past five years. Contentedness has been the sole clear exception – a third of age groups over 65 (32-33%) on average say they are content, while the figure for those in under-55 age groups has tended to be less than a quarter (22-25%). Being optimistic also bucks the trend, though more in the form of a ‘u-shape’ that dips towards and rebounds from middle-age – 23% of 18-24s and 75s said they were optimistic on average, falling to 17% among 45-54s.

For the rest of the emotions, there are several patterns, but all end up with fewer expressing that feeling towards the end of their adult life than at the beginning. Feeling sad, inspired or scared declines gradually with age, while happy, energetic, bored or lonely appears to decline until middle age and then broadly levels off. By contrast, being stressed seems to remain high (averaging around 47-50%) until somebody is in their mid-40s, before decreasing at a steady rate afterwards, settling at an average of 23% among over 75s.

Women are more likely to have been stressed, sad and scared over the last five years

While women are slightly more likely to say they’re happy – on average, 47% of women have been happy over the last five years, compared to 44% of men – the most marked gender differences on the mood tracker have come in terms of women being noticeably more likely to express certain negative emotions.

The largest gap is when it comes to stress, with 46% of women on average saying they were stressed, relative to only 35% of men. Sadness and being scared have also seen clear differences – nearly three in ten (29%) women on average say they were sad over the past five years, against only 21% of men, with women also being more likely to describe themselves as scared (14% vs 9%).

Covid was a particular stress for women – in our poll after the first lockdown was announced, the gender gap on those describing themselves as stressed widened to 17-points (41% of men vs 58% of women), with the gap in people feeling scared an even starker 19-points (26% vs 45%). Christmas also has an uneven impact on women, with the stress gap widening noticeably above average across every festive period for which we have data.

Younger women in particular are more likely to have reported negative moods than men the same age

It’s also the case that the gender gap is not equally distributed across generations, with young women especially more likely to describe their recent mood as having been sad or stressed compared to men the same age.

As stress declines with age among both men and women, so too does the gap between them. Among 18-24 year old women, on average 59% describes themselves as stressed, compared to 42% of 18-24 year old men – a 17-point gap. Among the oldest age group - the over 75s - women are still more likely to say they stressed, but the gap falls to 10 points, with 29% of older women being stressed against 19% of older men.

This pattern is also noticeably true of sadness. With the youngest adults, 41% of women describe themselves as sad, relative to only 28% of men, while the same is true of 17% of women and 11% of men over 75 – turning a 13-point gender gap into a six-point one.

But it’s not exclusively the case that the gender gap closes as people get older, with some moods it even flips. While more likely to describe themselves as sad or stressed, 18-24 year old women are also more likely to describe themselves as happy than men of their age (57% vs 52%). Women in over 65 age groups, however, are slightly less likely to say they felt happy in the past week. This is also true of feeling frustrated, which marginally less older women describe themselves as compared to older men, contrasting with the opposite among younger adults.

Might money be able to buy happiness after all?

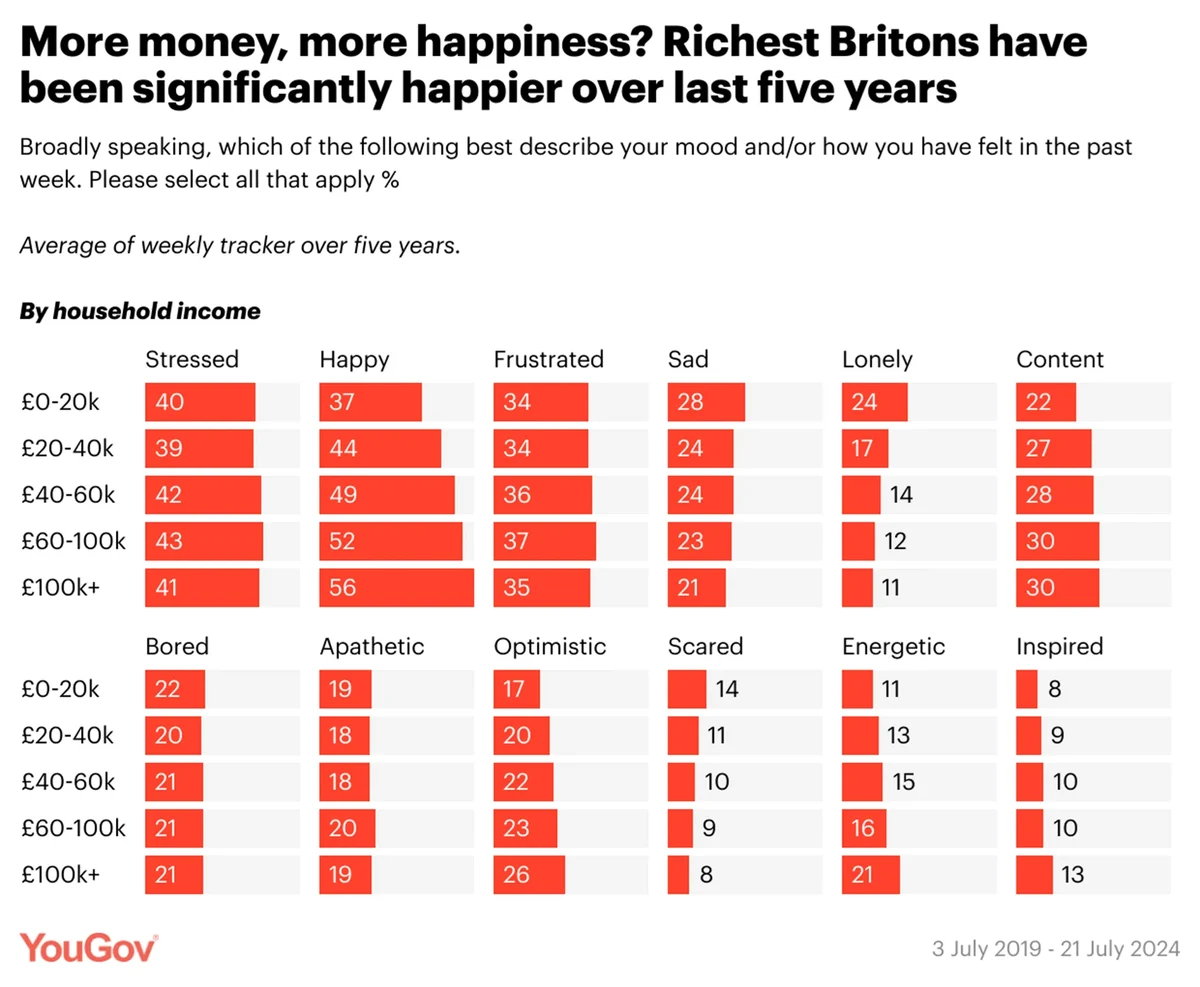

Whether money can buy happiness is seemingly answered by the mood tracker, with self-reported happiness varying more by income than any other mood. On average across the past five years, only 37% of those with a household income of less than £20,000 have said they were happy, compared to 56% of those whose households earn more than £100,000.

Sadness correspondingly declines with income, but the difference is smaller – 28% among the poorest households, against 21% for the wealthiest. Indeed, many moods show fairly limited variation – apathy, frustration, boredom and even whether they were stressed all having the richest group no more than 1% point different to the poorest.

The largest other differences are when it comes to being energetic, a feeling those in the wealthiest households (21%) are nearly twice as likely to express as those in the poorest (11%); optimism, felt on average by 26% of those with the highest household incomes and only 17% of those with the lowest incomes; and loneliness, which declines from one in four (24%) to one in nine (11%) as household income increases. As there is a negative correlation with age and loneliness on this tracker, the latter can’t merely be a function of lonely and poor pensioners.

Living with children not necessarily as stressful as often assumed

Few would disagree with the idea that having children has a big impact on your day-to-day life. We can therefore expect it to have something of a big impact on your day-to-day mood. Comparing 25-49 year olds with and without children in their household over the last five years certainly seems to bear this out, but it’s not really the negative effect that might be expected.

People with children in the household are more likely to claim they are happy – 49% have done so on average over the last five years, compared to 44% of their counterparts without children at home – while also being much less likely to describe their mood as apathetic (15% vs 24%), bored (21% vs 28%) or lonely (16% vs 23%).

Nonetheless, having children does not seem to have a sizeable impact on whether you’re stressed, frustrated or content, nor do children seem to particularly inspire or create optimism in their parents.

Britons getting eight hours sleep a night are the happiest, most content and least stressed

Mood is not the only thing YouGov have been tracking on a frequent basis over the last five years – weekly trackers also exist for things such as how much sleep Britons are getting, how much exercise we are doing and how much sex people are having. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the results to these do show clear correlations with people’s moods.

Britons who get around the recommended seven or eight hours sleep per night are much more likely to have better moods – being happier, less stressed or lonely, and more energetic and content than those who get too little or too much sleep per night.

For instance, a bit more than half (53%) of those getting eight hours sleep per night describe their mood as happy, compared to just 39% who spend ten or more hours in bed a day and only around a third (35%) of those sleeping for five hours.

On average, nearly as many eight-hour-sleepers describe themselves as content (31%) as stressed (34%), while the same figures for those getting five hours are a gulf apart – as few as 19% being content on the average week and 48% being stressed.

Regular exercise correlates with happiness, feeling energetic and being less stressed

A similar picture is true of those who regularly exercise. The more days a week someone does thirty minutes or more of physical exercise, the more likely they are to say they are happy, less likely to be stressed and, perhaps predictably, more likely to feel energetic.

But unlike with sleep, where the difference between the ‘ideal’ and non-‘ideal’ situations is particularly marked, the ‘improvements’ past a certain number of days of exercise are less significant. Half (50%) of those exercising three times a week describe their mood as happy, clearly more than the four in ten (39%) among those who voluntarily don’t exercise, but not significantly less than the 53% of those exercising six or seven times a week.

Excluding energetic-ness, which continues to increase with the number of weekly exercise sessions, this pattern is broadly true across the other identified moods, suggesting that – insofar as exercise has a positive impact – it is marginal gains beyond a certain point.

Britons who have sex four or more times a week are the least stressed

When it comes to how regularly Britons have sex, however, the correlations tend to be more straightforward. For instance, take feeling frustrated. Of sexually active people who haven’t had sex in the last week, 38% on average describe themselves as feeling frustrated, something that falls to 34% among those having sex two or three times a week. But there is then a similar jump again between the two-or-three-timers and those having sex four or more times a week, only 29% of which feel frustrated. This pattern is similarly true of feeling energetic or inspired.

Happiness is something of an exception here. Although people regularly having sex are happier than those who are not, it is not clear that those having lots of sex are more likely to be happy than those having a more moderate amount.

By contrast, there is a sizeable decrease in people reporting themselves as stressed among those having sex four or more times a week – only a third (33%), compared to 41% among those having sex two or three times a week and 44% among sexually active people who have not had sex in the past week.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the clearest splits is in loneliness – people having sex at least once per week are half as likely as those who are not sexually active (12% vs 24%) to say they feel lonely.

Of course, ultimately, these are just identifiable trends, not necessarily causal relationships – this data can’t say for instance whether people have healthy sleep patterns because they are happy or are happy because they have healthy sleep patterns, only that people who do sleep for the recommended amount of time do tend to be happier than those who don’t.

See the full results here

How do you feel about the last week, your life in general, and everything else? Have your say, join the YouGov panel, and get paid to share your thoughts. Sign up here.

Photo: Getty