The great majority of scientists agree; so do most senior politicians. Now voters are tending to think the same way: the floods are probably the result of climate change.

Of course, nobody can be certain that any specific event has been caused by the cumulative impact of carbon emissions. But the increasing frequency of extreme weather conditions in many parts of the world has been one of the main predictions of climate-change scientists; and it has duly come to pass.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

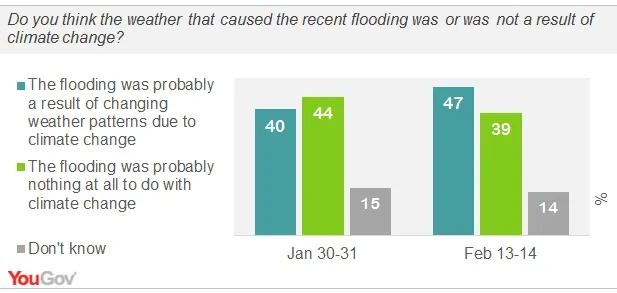

YouGov’s latest poll for the Sunday Times repeated a question we asked two weeks ago, after the floods had started to rise up the news agenda but before they invaded as much of southern England as they do now. Then, by a narrow 44-40% margin, the public thought that flooding was ‘probably nothing at all to do with climate change’. Now, voters divide 47-39% in support of the view that ‘the flooding was probably the result of changing weather patterns due to climate change’.

Those overall figures hide some significant differences among different groups. Labour and Lib Dem supporters back the climate-change explanation by almost two-to-one, while Conservative voters oppose this view by three-to-two and UKIP supporters by two-to-one. People under 40 side strongly with the climate-change view, while voters over 40 are evenly divided.

All of which poses a challenge to the main political parties. Climate change is one of those issues that refuse to sit comfortably with the normal rhythms of political contest. It needs consistent action over decades, and therefore requires a cross-party consensus, when normal politics is about dividing lines and short-term decisions. It needs global action when politics is mainly a national affair. And it needs people, companies and societies the world over to accept restrictions on their behaviour in the short term in order to save the world for our grandchildren – when national political contests normally reward those who promise plausible benefits in the years immediately ahead.

Our latest survey provides only slight encouragement to parties that want tougher action on climate change. The shift in attitudes is clear but still only modest. It needs to be larger and more sustained to change the terms of political trade.

Unless… Suppose David Cameron and Nick Clegg announced that they agreed with Ed Miliband’s warning over the weekend that Britain is ‘sleepwalking to a crisis’, and that ‘climate change threatens national security’ – and went on to commit themselves to working together on a long-term plan to protect the nation not just from extreme weather conditions but the other consequences of climate change.

In some ways, this would be like a rerun of what happened in 2008, when Miliband, as Energy Secretary, piloted the bill through Parliament that committed the UK to reduce its carbon emissions by 80% by 2050. Only five MPs opposed the bill. But that was before the recession start to bite into families’ living standards. Since then, tackling climate change has slipped down voters’ list of priorities.

Plainly a new consensus could reduce the electoral pain of any commitment to tough measures that, say, raised the cost of driving or flying. If all three main parties signed up to the same policies, the effect on their support should be broadly neutral (apart from Tory fears that this would drive more of their supporters into the arms of UKIP, which has consistently sided with the climate change deniers.) This would also hold out the prospect that similar policies would be sustained over a number of five-year parliaments.

Against this is the legitimate concern that political consensus denies choice and stifles debate. Democracy thrives on the dialectic of difference and dispute. Lazy thinking is more likely to be demolished through democratic argument than consensual group-think.

That is not all. Politicians do not rate high in public esteem. Voters may not be impressed by parties ganging together to tell us that we must change our ways. We could prove especially resistant to any cross-party move to raise our taxes.

This could be the case even if MPs, with one voice, tell us that all the money will be used to pay for vital flood defences and other measures to protect us from climate change – or that (if the parties adopt the proposition that the Liberal Democrats have advanced over the years) extra environmental taxes would be offset by lower taxes elsewhere – such as income tax or national insurance. Past YouGov research suggests that most of us think that governments would simply hang on to much of the extra tax revenues, and neither spend it as they promised, nor pass it on in the form of compensating tax cuts.

In short, if the floods are to lead to a significant change in policy towards climate change, a special form of political leadership is needed. It will be vital, but not enough, for Cameron, Miliband and Clegg to think long-term, to work together and to resist temptations to score party points. (That is, they must eschew accusations that ‘our opponents don’t take the issue seriously enough’ or, alternatively, that ‘our rivals would punish motorists and air passengers’)

Crucially, they need to do something else: act and speak in ways that restore public trust in politics itself. For political leadership to be effective, leaders must command respect. The floods have not just reminded us all how vulnerable we are to climate change, but how the ability of our political system to tackle long-term challenges is hobbled by our distrust of those we elect.

See the full Sunday Times results

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here