Just as the economy is beginning to recover, so is public confidence in the Government’s policies. But just as the economy is not yet restored to full health, neither is the Government’s standing.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times gives us the first reading of the public mood, and how it has changed, since the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement. We repeated a number of questions we have asked in the past. Although George Osborne’s speech dominated the news for only a few hours before we all learned of the death of Nelson Mandela, our figures suggest that the gradual lightening of the public mood in recent months has been maintained.

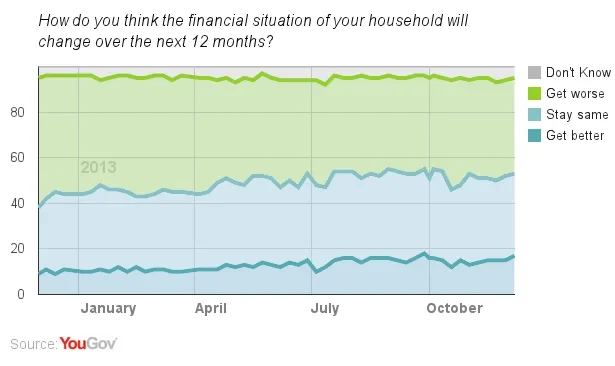

- 53% now expect to be at least as well off in a year’s time as they are now – up from 38% a year ago.

- In April, shortly after this year’s Budget, just 14% thought the economy was recovering. The figure is now 43%.

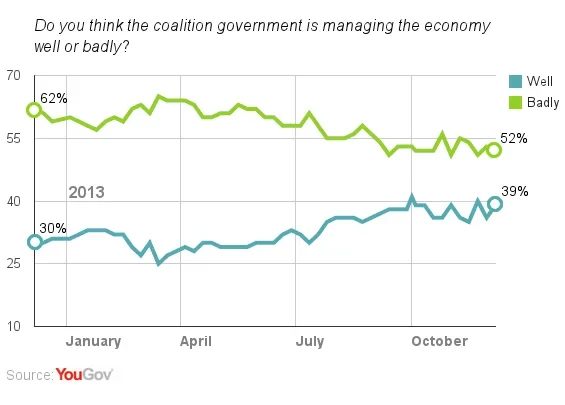

- 39% think the Government is managing the economy well, up from 30% a year ago.

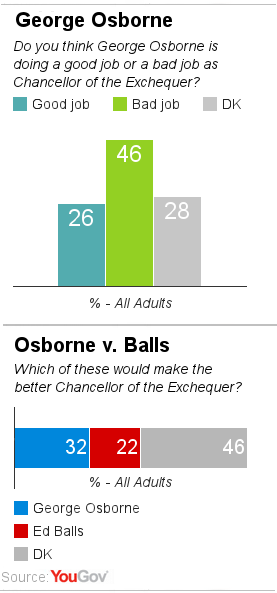

- George Osborne has opened up a ten-point lead over Ed Balls when people are asked who would make the better Chancellor, compared with a six point lead a year ago.

Now, before the Conservatives start crowing too loudly about these numbers, they should also note that:

- Half the public detect no signs of recovery yet.

- Just over half still think the Government is managing the economy badly.

- Only 26% think Osborne is doing his job well, and just 32% say he’s better than Balls. The figures suggest not that voters think highly of the Chancellor – rather that they think even worse of his shadow.

- While the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition is more trusted than Labour to deal with the public sector deficit and decide what’s best for the economy, Labour is trusted more ‘to make the right decisions about keeping down living costs’.

In short, the battle over the economy has not yet been settled. It could go either way between now and the general election. One might have thought that steady growth through 2014 would improve the Conservatives’ reputation for prudent management of the economy. Perhaps it will. But Ed Miliband has plainly had some success this autumn with the argument that ordinary folk are gaining no benefit from economic growth – indeed, that their living standards are being squeezed by below-inflation pay rises and such things as the rise in gas and electricity prices.

The challenge facing the Tories is to ensure that ‘hard-working families’ – the group that politicians in all parties are trying to woo – are invited to the party if economic growth is sustained.

Last week’s announcement of a £50 reduction in energy costs for the average family is plainly intended as a way to fend off Labour’s cost-of-living challenge. It’s a fair bet that next year’s Autumn Statement will herald tax cuts in 2015 in order to boost take-home pay. But will voters say ‘thank you’ and reward Osborne by keeping the Tories in power, or will they curse the Chancellor for trying on a pre-election con trick, and vote Labour?

In the unlikely event that Osborne seeks my advice, I would suggest that he spend the next 12 months trying to convince voters (a) that economic growth is here to stay, (b) that tax cuts will be a reward for prudent economic management, not simply a pre-election bribe and (c) that the Conservatives not only meant that we were ‘all in it together’ in fighting austerity, but that we shall all thrive together as the recovery gather pace. He is on the way to achieving (a) but still some way off achieving (b) and (c).

Meanwhile, a further finding from our post-Autumn-Statement survey should concern politicians in all parties. We asked about the Government’s plans to increase the retirement age over the next thirty years. This is not a partisan issue. The arithmetic is compelling: as people live longer, then either people in work must pay ever higher taxes in order to provide state pensions to everyone over 65; or people will have to work longer and retire later.

Our survey shows that there is widespread resistance to raising the retirement age. This is what we asked, and what we found:

Q. The Chancellor has said that the retirement age for state pensions will rise to 68 in the mid-2030's and 69 in the late 2040s. People now in their twenties may have to work until they are 70 before they receive a state pension. Do you support or oppose this?Support - with people living longer, we won't be able in the long run to afford keeping the pension age at 65: 32%Oppose - people starting out these days have enough challenges; we should not force them to continue working until they are 70: 57%Dont know: 11%Should past governments have acted sooner to raise the retirement age and lift some of the tax burden on today’s workers? After all, millions of people now in their sixties (interest declared: including me) belong to the lucky generation that never paid university fees, bought their first home when they were a fraction of today’s prices, and won’t be affected by the future rise in retirement age. So we asked a further question: This controversy is not just about the future. To some extent it also concerns the present and recent past. Women have seen the age at which they qualify for a state pension rise from 60 to 65, the same age as men. But the male retirement age has stayed at 65 for some decades, even though life expectancy has been rising steadily.

Q: Do you agree or disagree with this statement:'We should have started to raise the pension age years ago. Today's recently retired people have never been as well of as they are today; they are benefitting unfairly at the cost of younger workers who have to pay higher taxes as a result'Agree: 35%Disagree: 53%Don't know: 11%Compared with headlines about freezing the price of energy, or cutting our fuel bills by £1 a week, future pension policy involves seriously large sums of money. Our findings do not suggest that the Government should abandon its long-term plans; public opinion is sadly unable to revise the laws of arithmetic or to reverse economic gravity. Rather, they should be taken as a sign of how much work needs to be done to persuade voters of the need to raise the retirement age. Not surprisingly, the over 60s reject this view by three-to-one; but so do the under 60s by 48% to 39%.

I suspect that our findings reflect the sorry reputation of Britain’s political classes. Even when the economic logic is overwhelming, and the parties are broadly united, the public remains unconvinced by what they say.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here