Research produced for this year’s YouGov-Cambridge Forum on the role of the state finds Britain in flux over the democratic accountability of foreign and security policy

As minsters scramble to reaffirm Western alliances and Downing Street recovers from its first defeat in a Commons vote on military action in modern times, research for this year’s YouGov-Cambridge Forum suggests the British public want a larger role for Parliament in authorising military involvement.

See the full YouGov CambridgeProgramme report: Public Opinion and the Evolving State

Parliament’s role: advantages and disadvantages

In the past, Parliament never voted directly on war itself. Even in the two most crucial Commons debates of the Second World War the motion before MPs was to ‘adjourn the House,’ to debate the issue without voting. Only since the decision to support the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 have MPs voted explicitly on such matters.

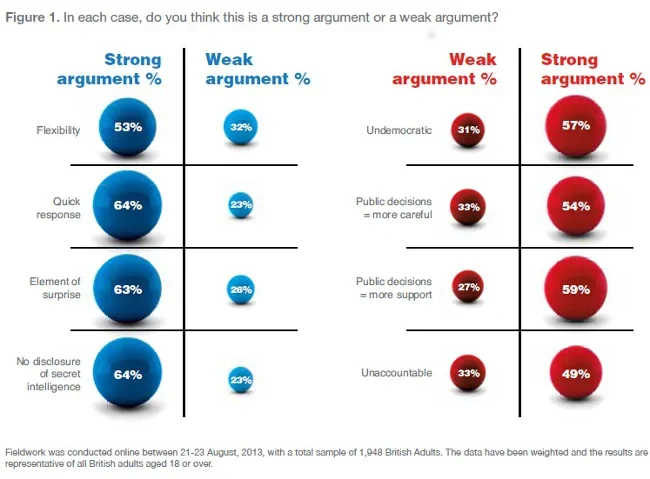

The old system looked odd, but it was flexible. The new system looks more sensible, but it raises the vital question of where to draw the line between those decisions that are properly left to ministers and those that should be made by Parliament – or even the wider electorate. How strong are each of four reasons on the two sides of the argument?

Three of the four advantages are considered strong by 63-64% of the public: the capacity to surprise an enemy, the ability to react quickly to events and the ability to use secret intelligence that cannot be disclosed. For the disadvantages, the figures range from 59% for the merit of going to war on the basis of an open and democratic vote, to 49% for Parliament being able to hold ministers to account if things go wrong.

When the advantages and disadvantages are laid out, most people can see that the issue is far from simple. We should not be surprised, then, that different circumstances provoke different responses as to how decisions should be taken.

The scale of democratic oversight

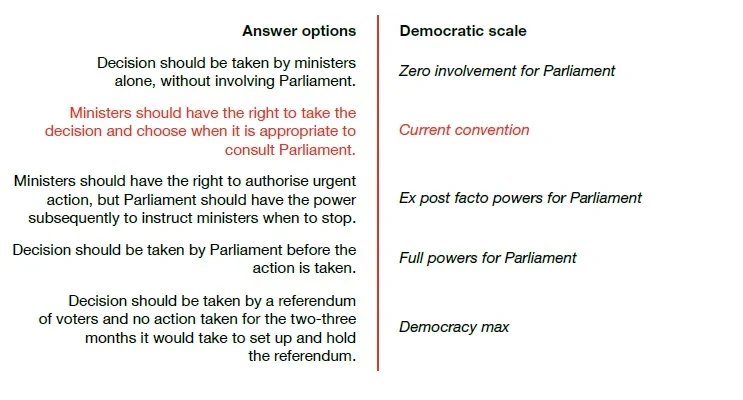

Respondents were further asked how the nation should decide on a range of foreign policy actions, and given the following options for deciding on action, spanning a democratic scale from ministers acting entirely alone to following the current convention (highlighted below) to Parliament having ex post facto or full war powers and finally to the ‘democracy max’ option: a public referendum.

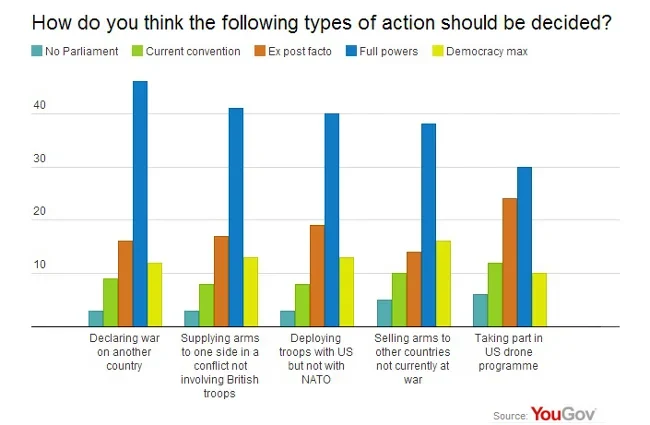

The range of foreign policy actions can arguably be categorised into two broad groups. In the first, below, we see a number of scenarios where the public shows a notable preference for giving full powers to Parliament to decide before any action is taken.

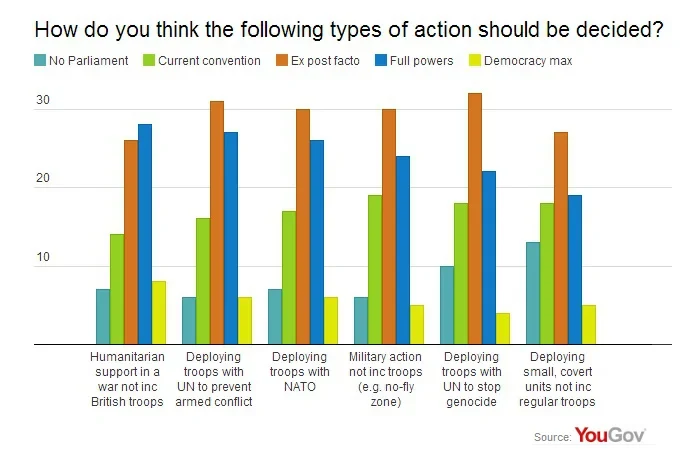

In the second group, below, we see a number of scenarios where the percentage of those preferring to give full powers to Parliament falls more evenly with, or below, the figure for those willing to give ministers the right to authorise action in the first instance, followed by ex post facto powers for Parliament to call a stop.

In other words, respondents lean towards giving full powers to Parliament in authorising war or military involvement beyond multilateral commitments, keeping the peace and sticking to the air. But they also recognise a need for ministers to act without Parliament’s word, at least in the first instance, particularly in cases involving humanitarian urgency, secrecy or multilateral intervention.

In light of the recent debate on air strikes against Syria, it is also notable that our poll (conducted shortly before the recent Commons debate) found that 55% thought ministers should have the right to authorise at least the initial military action when no ground troops are involved, while just 29% want the decision to be taken by Parliament (24%) or a referendum (5%). The Prime Minister appears to have lost public support because of his handling of this particular crisis, not because voters rejected the principle of governments acting on our behalf.

Following the House of Commons defeat, yesterday a cross-party group of senior politicans, including Labour's Lord Mandelson, the Conservative's Lord Howard and the Liberal Democrat's Lord Ashdown, wrote to the three main party leaders urging them not to see the vote on Syria as the end of Britain's commitment to humanitarian intervention. The letter states: "Whatever one's views on the vote, this must not be the point in British history at which we reach a fork in the road and choose to abandon such an important notion of collective global responsibility."

Image: Getty