You’d probably have to search quite hard to find many people in Britain who want Donald Trump to win next week’s American presidential election. The 45th President of the United States is, even in American terms, an oddity, to say the least. But in the eyes of most of us Europeans he’s just beyond the pale, not the sort of man you’d allow into polite political company let alone elect as leader of the free world. But whatever we may think of the personal qualities of Mr Trump or, for that matter, of all the other presidential candidates we’ve seen come and go over the years, there is always a need for us to set aside mere squeamishness and to ask a hard-headed question: which candidate would better serve British interests? So, this time, who would it be: Donald Trump or Joe Biden?

Usually American presidential elections attract just mild interest and offer a certain amount of entertainment over this side of the Atlantic. We tend not to get too worked up about them. If we veer to the right we will probably favour the Republican candidate and if we are on the left it’s the Democrat. But it’s seldom a big deal for most of us because the really divisive issues in American presidential elections have almost always been about domestic matters. On foreign policy the two American parties have broadly followed much the same path - at least since World War Two. Vietnam was an exception.

But the two big parties have been committed to free trade and to what has been labelled ‘internationalism’. That has come to mean establishing and defending international organisations of one sort and another to create a global, rules-based order for settling disputes and promoting the interests and values of the free world. And Britain has been able to rely on presidents of both parties to uphold the ‘special relationship’ between the two countries, even while it has rarely been clear what that special relationship amounts to. We tend to use the expression rather more frequently than them – for pretty obvious reasons.

But Donald Trump has ripped up most of this. He has aggressively pursued an ‘America First’ policy which is highly protectionist on trade and which has seen him ready, even eager, to dismantle many of the international institutions that have kept the global order going. He’s made the World Trade Organisation virtually inoperable. He’s stopped US funding of the World Health Organisation. He’s pulled America out of the Paris Accord on tackling climate change. He’s unilaterally abandoned the Iran deal jointly negotiated with America’s European allies to rein in the Islamic state’s nuclear ambitions. He’s called NATO ‘obsolete’, scorned its European members and is in the process of pulling large numbers of American troops out of Germany. The list goes on.

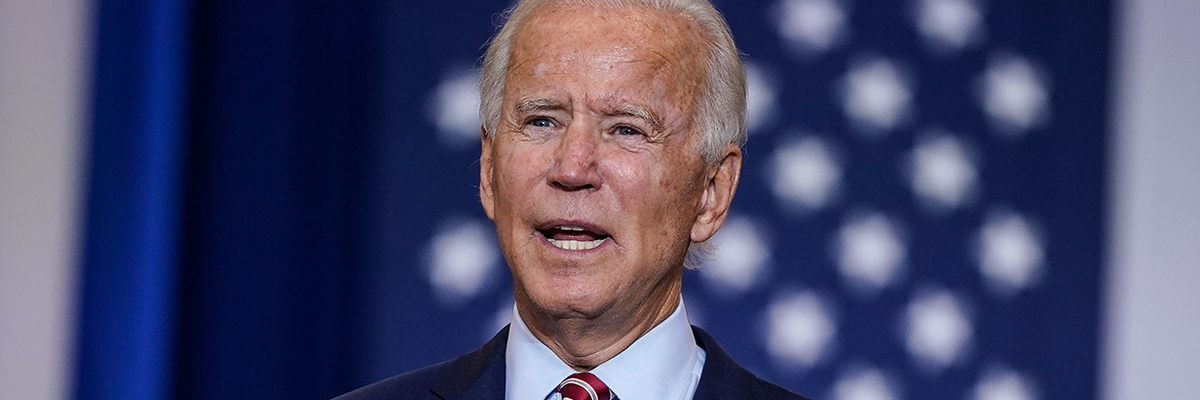

So if restoring the old internationalist way of running the free world is what we want, the choice is pretty obvious: anyone but Trump. Biden is our favourite. The Democrat presidential candidate, who was Vice President under Barack Obama, is steeped in the old internationalist way of doing things. He wants to bind the wounds of NATO, sign up again to the Paris Accords, revive the Iran deal, and rebuild international organisations such as the WTO and the WHO. In short he wants to return to as much of ‘business as usual’ as he can and ‘business as usual’ used to suit us just fine.

But this is perhaps too simple a picture. For one thing, the world has moved on in the four years since Mr Biden hovered behind President Obama’s shoulder. For all his attachment to internationalism, a President Biden might have to have second thoughts about just how much he should still be attached to the principles of free trade. After all, Mr Trump’s surprising success at the last election was in part due to the kicking and squealing of American voters in the old rust belt against what foreign competition had done to their jobs, their livelihoods and their children’s future. Clocks don’t always get turned back easily.

And the world has changed very radically for Britain too over those last four years. By the time the newly-elected president attends his inaugural on 20 January next year (assuming everyone agrees who’s who’s won!) Britain will finally and fully have left the European Union. Would it be better for us if the next president were a committed supporter of Brexit? If so, Britain should surely be hoping that Mr Trump will be re-elected because he has always been an enthusiast for Brexit. Indeed one of the very first people to leap on a plane and head straight to Trump Tower in New York to congratulate the president-elect on the very first day after the election he so surprisingly won back in 2016 was none other than our own Nigel Farage, the British politician who could be said to have done more than any other to bring Brexit about.

Joe Biden, on the other hand, has never made any secret of his belief that he thought Brexit barking. One of the tenets of the old internationalist consensus in the United States was that the European Union was a good thing and that its ally, Britain, should most certainly be a part of it. Mr Biden has not changed his mind. If he enters the White House next January it is most unlikely that Boris Johnson will be the first foreign leader to be invited to meet him there, as Theresa May was by Donald Trump back in 2017; it’s much more likely that Angela Merkel will be asked to do the honours.

And this isn’t just about diplomatic niceties. One of the consequences of Brexit is that, whether or not Britain and the EU do manage to sign a trade deal before Britain leaves at the end of this year, we shall be looking to sign new trade deals of our own with other countries round the world and none more importantly than with the United States. Boris Johnson’s government has gone a long way to draw one up with the Trump administration and would hope to be merely dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s if Mr Trump were still in power in late January. With President Biden, however, it would be back to the drawing board. Indeed it might be far worse than that. The Obama/Biden administration famously warned before the Brexit referendum that if Britain were to find itself outside the EU and wanting to negotiate a new trade deal with the US, it would discover it would be ‘at the back of the queue’.

President Trump’s pro-Brexit stance seems as much to do with his pro-Britishness as with his anti-EU views. He ostentatiously restored a bust of Churchill to its place in the Oval Office after it had been removed by his predecessor. And of course he has gone out of his way not only to advertise his pro-British credentials but to tell the world he is ‘pro-Boris’ too. He even went so far as to say that the Prime Minister was ‘Britain’s Trump’, an encomium Mr Johnson may or may not have welcomed.

Whether he did or not, the issue of personal chemistry can never be overlooked when asking the hard-headed question of which presidential candidate would be best for Britain. Going back as far as the relationship between Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill in the Second World War, it has mattered how the American President and the British Prime Minister get on. And it mattered in terms of British interests. President Eisenhower and the British prime minister Antony Eden fell out over Suez and that was the end of both Eden and of Britain’s illusions about its status in the post-war world. Kennedy and Macmillan related like son and father, it’s said, and the result was close cooperation on nuclear weapons. Famously Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher got on like a house on fire, not only because they viewed the world through the same ideological spectacles but because they liked each other. The received wisdom deriving from all this is that a good personal relationship between president and prime minister is of priceless value.

But that may be exaggerating things. Reagan and Thatcher may have been as close as they conceivably could be, yet it didn’t stop the American president invading Grenada, part of Her Majesty’s Commonwealth, without even giving his friend in Downing Street advance warning. And some would argue that the personal closeness of Tony Blair to George W Bush was disastrous for British interests in that it led to the country’s involvement in the invasion of Iraq which almost all other European leaders thought a barmy idea. (Mr Blair would give a different account.)

If personal chemistry remains a factor, however, it’s clear that for Boris Johnson, with four years at least nominally left in office before he faces an election of his own, the re-election of his friend Donald would be the better outcome. In the lead-up to next week’s American election, British diplomats have been wholly unable to do what they usually do and develop close links with both sides in order to hedge against either outcome. That’s because Joe Biden’s camp hasn’t wanted to play ball. This may in part be because his aides have been anxious to keep a distance from all foreign governments, after the rumpus caused at the last election by the alleged interference of the Russian government in the campaign. Nonetheless there is every reason to think a Trump White House will be much more friendly with a Johnson Downing Street than a Biden White House

So in making the assessment of which outcome of next week’s election would be best for Britain, it’s not quite as clear-cut as it would be if the only criterion were the personal character of each candidate. But that factor cannot be excluded from the calculation. There’s no getting around the fact that President Trump is a loose cannon and perhaps a dangerously loose one at that. Even in relation to the matter of personal chemistry he is utterly unpredictable. Ask President Xi or the leader of North Korea about that. Mr Johnson might be the Donald’s closest, bestest chum this week and a ‘hopeless loser’, an ‘embarrasment to Britain’ next. In terms of what a re-elected President Trump might actually do when he never has to face the electorate again, there’s no saying. And what his re-election might imply for the way politics is conducted henceforth not only in America but in other countries like our own, looking on astonished at his success, does not perhaps bear thinking about.

So who should Britain hope will win next week? Let us know what you think, and why.