There is no evidence to suggest that polling is undercounting those who don’t support anti-coronavirus measures

If you were to look at some parts of Twitter, or follow the conversations on some phone-in radio shows, you may conclude that Britain is a country in open rebellion about the impositions the government has put in place to fight coronavirus.

The reality could not be further from the truth.

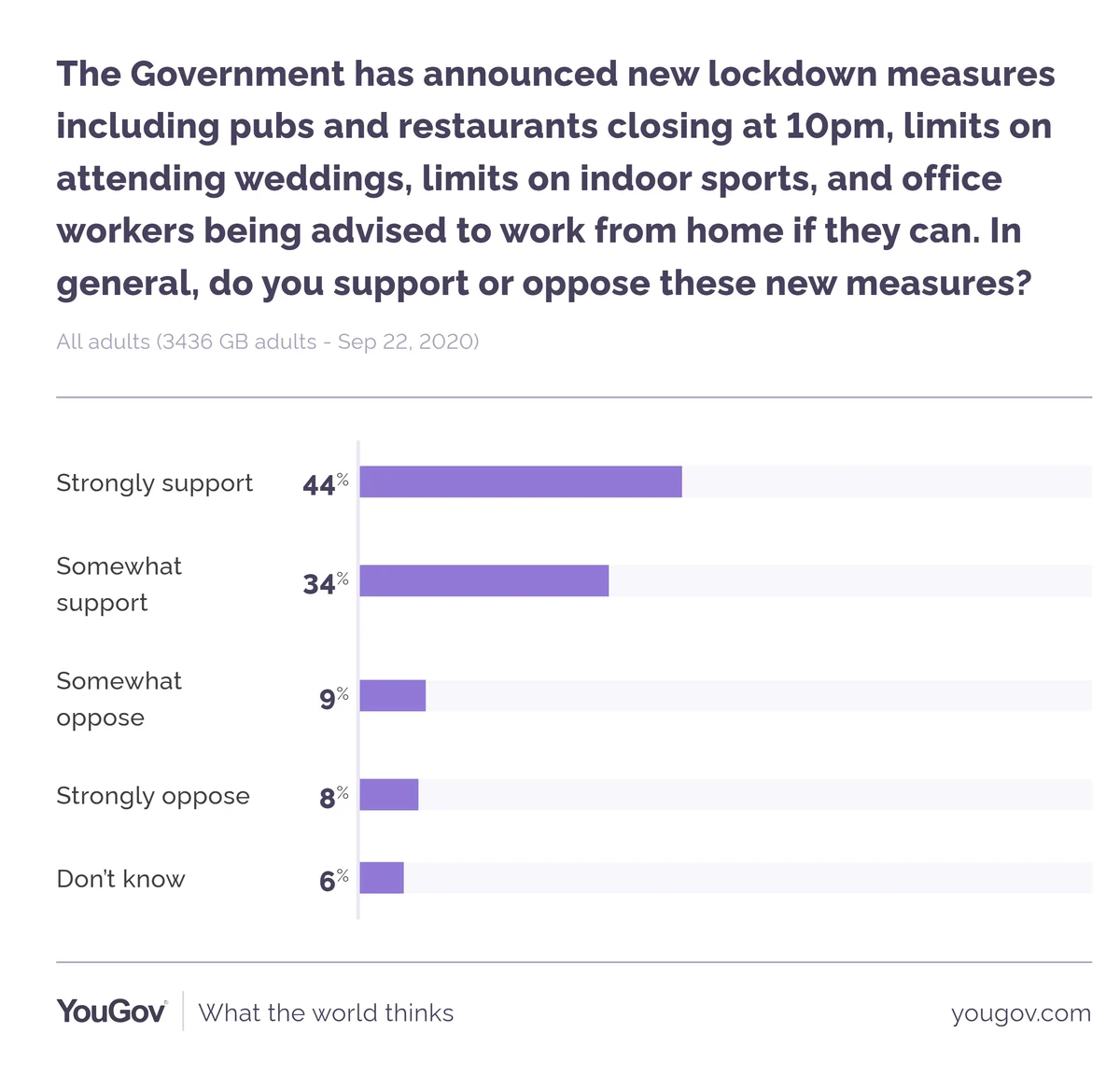

Our latest opinion poll shows that an overwhelming majority (78%) of the country backs the new lockdown measures announced by the Prime Minister yesterday, and the main criticism of the package is that it doesn’t go far enough.

This has been a consistent theme throughout the entire crisis, with large majorities of the public backing every restriction the government has put in place.

The initial lockdown in March was supported by fully 93% of the population, making it one of the most popular policies we have ever tested.

Those who oppose the latest raft of measures, who seems so loud in some quarters, represent just 17% of the population. It is slightly higher among some groups, most notably the young, but it is a minority among all demographic groups. Overall levels of opposition are comparable to other niche views such as opposing the monarchy or denying man-made climate change.

In response to these conclusive polling results some have mused that the polling might be missing out on a “silent majority” in the country, who are answering polling questions in a way that makes them sound like good moral people who support restrictions, when they are actually opposed. This is usually described as “social desirability bias”.

There are multiple reasons why that is unlikely to be true. Firstly, most UK polling, including all YouGov polling, is conducted online meaning that all responses are anonymous and there is no human contact. It is ticking a box on a computer in the privacy of your own home with no interviewer to impress, meaning responses will be a lot more honest.

Secondly, if it were the case that lockdown measures were unpopular in reality then we would not have seen such a surge in support for both the government and Boris Johnson after the first measures were introduced earlier this year.

Finally, it is very rare that the direction of social desirability bias in polling is towards those who are shouting loudest about social desirability bias. To be blunt, if people are not so shy that they are willing to loudly and forcefully express a view on Twitter, they are unlikely to be so shy that they wouldn’t admit it in an anonymous poll.

None of this is to say that we can rule out the possibility of some type of bias, and it is very difficult to prove either way. But when we have seen it in the past, for example with “Shy Tories” in the 1990s when people didn’t admit they were voting Conservative, the effect has amounted to a very small proportion of the overall population.

Even if an effect of that size were at play here, it would still mean around three quarters of the population supporting new restrictions.

So overall the picture is clear. As a country, we overwhelmingly support lockdowns and restrictions if the government say they are necessary, including the latest raft of measures. And while it’s obviously fine to disagree, those that do aren’t in a “silent majority” but rather in “loud minority”.