Concern about energy bills has seemingly dropped off a cliff since 2014. But support for state intervention in the household energy market remains strong and fits a wider trend in British politics.

Among the more contentious items in Theresa May’s General Election manifesto was the revamping of an older Labour Party pledge to intervene in the household energy market.

Back in September 2013, then Opposition leader Ed Miliband proposed a 20-month price freeze on gas and electricity costs, which proved popular with the public but stirred a backlash from the conservative press for allegedly harking back to militant socialism.

As the ex-Labour chief duly noted on Twitter three years later, there was little such reaction when the Conservative Party proposed a similar idea in 2017, including a price cap (rather than a freeze) to protect against “unfair energy price rises” for the roughly 17 million households on standard variable tariffs.

The proposal was quickly dropped following a disappointing election result for the Tories. But the energy market regulator Ofgem then announced alternative plans for protecting vulnerable energy consumers, including a “safeguard tariff” for low-income customers who qualify for the “warm home discount”.

Critics described these plans as a watering down of policy that would only protect a smaller 2.2 million customers from punitive bill hikes, while allowing energy companies to recoup the cost by allegedly “milking the rest of us”. Others, including a former regulator, questioned Ofgem's ability to set even this cap.

Such is the current state of policy debate on household energy. As repeat YouGov polling suggests, however, the issue may have become more of a political concern than a public one over recent years.

In research for the YouGov-Cambridge Centre, we fielded similar surveys to representative samples of the British public shortly after the Miliband pledge in early 2014 and just before the recent General Election in May 2017.

Both the public saliency and perceived burden of household energy bills have significantly dropped.

In 2014, 38% of respondents ranked it among the top three issues facing the country, while 8% further called it the single most important issue.

In June 2017, by contrast, energy prices had seemingly all but vanished from consciousness, with only 4% ranking it in the top three issues and 0% calling it the single most important issue.

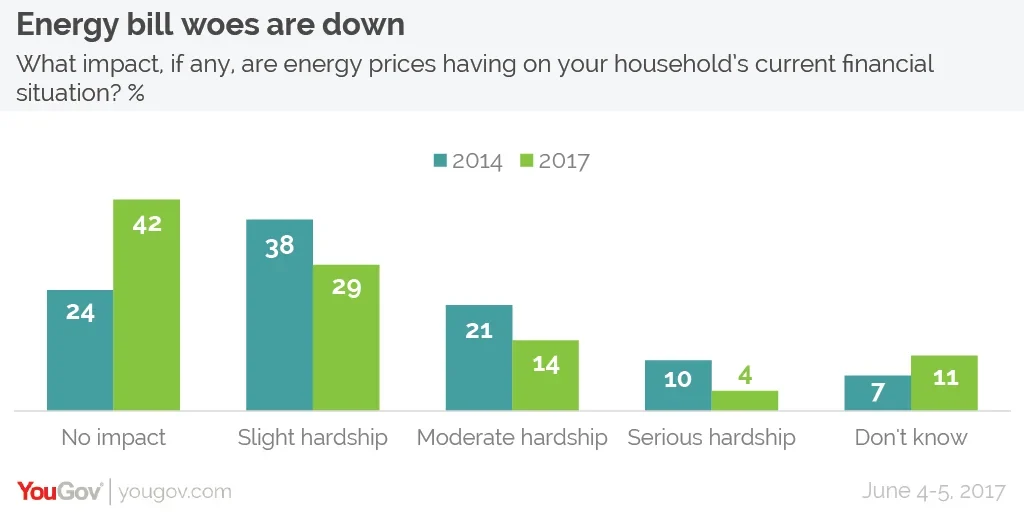

Moreover, those claiming that energy bills imposed “no impact” on their household’s financial situation had jumped from 24% to 42%, while those saying energy bills imposed “serious hardship” had more than halved from 10% to 4%.

Such change is likely explained by a sustained decline in wholesale energy prices since 2014. But while public concern about energy bills has markedly dissipated, support for state intervention in the household energy market remains strong.

52% backed the Miliband freeze in 2014 while 68% endorsed the May cap in 2017. Other radical policies have also maintained substantial backing, such as nationalising the energy companies (41% in 2014/39% in 2017) and a windfall tax on energy companies (42% in 2014/39% in 2017).

Party allegiance does of course play a role. In each survey, we also randomly split the sample so that roughly half of respondents only saw the proposals while the other half also saw which party or politician had suggested them. Naturally, associating policy with political tribe has a clear effect on results, shifting voters towards proposals from their own party and, in particular, away from those of others. For example, without putting a political label on the proposal for a tariff cap in 2017, lowest approval is actually found among 2015 Conservative voters (68%), compared with 71% for both Labour and 70% for Lib Dems. But when the policy is identified with “Theresa May and the Conservatives”, the results are significantly different: 73% support among Conservatives, compared with 55% for Labour and 47% for Lib Dems.

In the bigger picture, the household energy market now looks like a microcosm for change in British economic debate.

In the period from Soviet to Lehman collapse, the great ideological dispute between left and right in Western politics seemed to be over. Neoliberalism had supposedly won the day with its premise that markets make better economic decision-makers than governments, and that the latter should keep to a minimal role of maintaining a benign macroeconomic environment, namely by reducing taxation and regulation while passing numerous functions to the private sector.

Global recession from 2008 then undermined the perceived infallibility of markets and rekindled a moribund debate on the appropriate balance between socialism and capitalism.

Long-running studies like the British Social Attitudes Survey suggest public attitudes to the economic role of government have seen limited change over the past twenty years, with a fairly steady preference for state action to promote jobs but shrinking support for “propping up” declining industries.

As YouGov polling has also shown in recent years, however, proposals for nationalisation are now consistently popular with a large segment of the public, while faith in the behaviour of business has been falling away, according to the YouGov-Cambridge Public-Policy Tracker.

Such findings highlight a new willingness in British public opinion to question old assumptions of the Thatcher-Blair consensus on neoliberal economics. The recent Tory election manifesto sought to mine this sentiment by proposing an end to “untrammelled free markets” and the “cult of selfish individualism”. But the Labour manifesto predictably went much further, with calls for a “fat cat tax" on business and creating new state-owned champions, including the re-nationalising of some water, rail, energy and postal services.

How times change. Miliband’s original freeze policy caused shock in the energy industry but was widely perceived as a moment of populist opportunism. Now it seems more like a weathervane for political change. Household energy bills were just a start.