Labour's position in the polls is poor, but it's not uniquely terrible either

Labour’s performance in polls and in mid-term elections has become a political football – not just the usual rather routine spinning of parties saying how well they are doing, but a key faultline in Labour’s internal leadership battle. A key argument of Jeremy Corbyn’s critics is that he is an electoral liability – therefore they highlight anything suggesting that Labour are doing badly. In contrast Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters brandish anything that can be presented as a sign that Labour are actually doing well.

Which side is right? A lot of what both sides say is exaggerated or unfair. Some of it is just downright untrue. For what it’s worth, this is an attempt to unpick the evidence and look at it as fairly as I can. I expect, therefore, that this piece will not make anyone happy. It’s not going to say that Labour polls are the worst for any party ever, nor that Jeremy Corbyn is actually the messiah. It’s also quite long, so if you’re hoping for either of those conclusions, perhaps give it a skip.

Labour in the polls

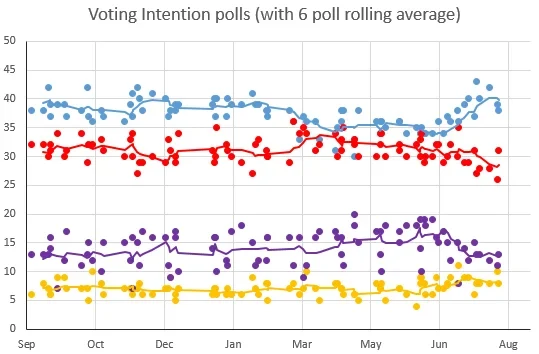

Polls in August so far have shown Labour between 7 and 14 points behind the Conservatives. However, this is probably not a fair yardstick to judge them upon given Theresa May is enjoying a honeymoon in the polls. A more reasonable point of comparison is to go back earlier in the year, before the EU referendum. Between the March budget and the EU referendum there was an average Conservative lead in the polls of three points.

There have been frequent claims that Labour were equal to (or even ahead of) the Tories before Labour’s leadership troubles erupted. This is a disingenuous claim at best, and seems to rest wholly upon cherry-picking individual polls. There was a single Survation poll straight after the referendum result that had the Conservatives and Labour equal, but an ICM poll conducted at the same time had a Tory lead of four points and the average position at the time was a Tory lead of about three points. At no point this year have the polls ever shown a consistent Labour lead (and the last poll to show Labour ahead was in April).

A typical opinion poll has a margin of error of +/-3%. That means if the actual position is a Tory lead of about three points, then random chance will sometimes spit out individual polls showing Labour neck-and-neck or even just ahead, or, at the other extreme, showing Tory leads of six points or more. Anyone seeking to honestly describe the state of the parties cannot reasonably just pick one of those outlying polls and claim it reflects the actual picture, ignoring the wider average. The only reasonable way of judging support is to take an average across many polls.

So, if Labour were on average 3 points behind the Tories, would that be good or bad for an opposition? The typical pattern of opinion polls is that oppositions open up leads in mid-term polls (so-called “mid-term blues”) and then governments recover as the election approaches. Obviously this does not always happen, but opposition parties that go on to win the next general election have usually opened up towering leads in mid-term polls. Oppositions that have not secured large leads in mid-term typically get hammered at the subsequent general election. On those grounds, an opposition that’s still three points behind mid-term is heading for disaster.

However, there’s an important caveat… oppositions that go on to win almost always have big leads mid-term. But that doesn’t mean they have big leads throughout the whole Parliament. In the first half of 2006 David’s Cameron’s Conservatives only had a lead of 2 points or so; in early 1975 the Conservatives were still behind Labour. In contrast, in early 1980 Labour had a healthy lead over the Conservatives. How well or badly a party was doing in the polls this early in the Parliamentary term is really not much of a guide as to how well they will end up doing at the next election – too much depends on the performance of the government in power and what triumphs and disasters fall upon them over the next three years.

Where the polls are more alarming for Labour is some of the underlying questions. Labour were ahead in voting intention throughout most of the last Parliament, but were behind on economic competence and leadership, which are normally seen as important drivers of voting intention (the ultimate explanation of this apparent paradox was, of course, that the voting intention polls were wrong). If we look at economic questions and leadership questions now Labour’s position looks bleak.

On who would make the best Prime Minister Theresa May leads Jeremy Corbyn by 58% to 12% with YouGov, by 58% to 19% with ComRes. YouGov currently give the Conservatives an 18 point lead on running the economy, when ComRes last asked in March the Tories had a 16 point lead. Looking at MORI’s long term approval trackers Jeremy Corbyn’s net approval rating is minus 41 – already pushing at Ed Miliband’s lowest of minus 44 (and those depths took Miliband years). Corbyn’s favourability rating in ComRes last week was minus 28, worse than everyone else they asked about but Trump.

Labour at the ballot box

The other way of measuring support are mid-term elections. Just like opinion polls there is a typical pattern of oppositions doing well in mid-term contests and then falling back come a general election. Oppositions that scrape wins in mid-term normally go on to lose the following general election; oppositions that go on to win have usually crushed the government mid-term.

Local elections

The results of the 2016 local elections were spun for all they were worth by both sides within Labour. Opponents of Jeremy Corbyn made much of Labour failing to gain councillors in 2016, but in fairness this was because Ed Miliband had already won the low hanging fruit when those wards were last contested in 2012. There were some social media memes claiming Corbyn did well in the local elections in 2016 because he got a higher share of the seats contested than Blair won in 1995 or Cameron won in 2006 – this is misleading because a different group of seats are up at each set of local elections (Blair’s first local elections in 1995 were the all-out district councils, including lots of Tory territory; Cameron’s first in 2006 were largely London and the Metropolitan boroughs, so were on very Labour territory).

The fairest way of judging local election performance are the national equivalent shares of the vote calculated by Rallings and Thrasher – indeed, that’s the whole point of them. The Rallings and Thrasher figures are a projection of what the result would be if there were local elections across all of Britain, an attempt to even out the cyclical differences and make one year’s results comparable to other year’s results.

At the 2016 locals the R&T projection was CON 32%, LAB 33%, LDEM 14%, UKIP 12%; a one point lead for Labour. Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters have presented this as a sign of Labour doing well, on the grounds they beat the Conservatives. The TSSA have presented it as positive because it is a four point swing from the R&T projection of support at the local elections in 2015.

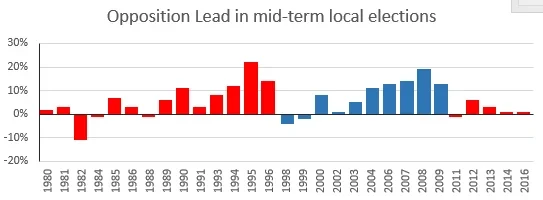

These claims are flawed. Looking at historical comparisons, Labour’s performance in the 2016 local elections was pretty mediocre compared to previous oppositions. The graph below shows the main opposition party’s lead over the government at mid-term local elections since 1981.

It is normal for the opposition party to win local elections mid-term and a lead of just one point is a pretty poor result comparatively. It is not, as some of Corbyn’s detractors have claimed, the worst local election performance for decades (Ed Miliband’s Labour did a little worse in 2011 and William Hague did significantly worse for the Tories in 1998) but it is the sort of local election performance heralding failure at the next general election. It’s the same lead that IDS got for the Tories in 2002, hardly a happy precedent.

As with voting intention polls, if you look at oppositions that went on to win the next election, they won mid-term local elections hands down. Cameron and Blair both consistently secured double-digit leads at local elections. Oppositions that were roughly neck-and-neck with the government in local elections (like Labour in 1984, 1988 and 2011, or the Tories in 2002) went on to be defeated at the following election.

In summary, the local election performance from Labour this year is not the unprecedented disaster Corbyn’s opponents have claimed – others have done worse – but neither is it in any way positive news. It is a mediocre result, with far more in common with those oppositions that have gone onto defeat than those oppositions who have ended up winning the next election.

Scotland, Wales and London

On the same day as the local elections were the elections to Scotland, Wales and London. These were a mixed bag for Labour – in Scotland they were again crushed by the SNP and trailed behind the Tories in terms of seats; in Wales they largely maintained their position, losing a single seat; in London Sadiq Khan won the mayoralty from the Conservatives. On the face of it this is one bad result, one mediocre result and one good.

Labour’s position in Scotland is dire, but I think it unfair to blame it upon Corbyn: the way politics has changed in Scotland since the referendum is probably beyond the control of any Labour leader, and it began long before Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Wales is a devolved assembly where presumably many voters would have been passing judgement upon Labour’s performance in governing Wales – though the results were pretty middle-of-the-road for Labour anyway.

In London it is difficult to know how much voting patterns are down to the party and how much they are down to the politicians running for the mayoralty – was it a victory for Labour, or for Sadiq? Either way, the result is somewhat less impressive that it looks. In the first round, Sadiq Khan was nine points ahead of Zac Goldsmith,typical of other recent London elections: in the 2015 general election Labour came top in London by 9 points; in the 2012 London assembly election Labour won by 9 points. The anomaly was the 2012 mayoral election, when Boris Johnson won through some combination of his electoral appeal and/or Ken Livingstone’s lack of it. London is now a Labour-leaning city, and winning by nine points is just repeating what Ed Miliband managed in 2015. That’s not to be snooty about Sadiq Khan’s achievement in winning the mayoralty back for Labour, but it doesn’t indicate any gain in support since 2015.

By-elections

The final bit of electoral evidence offered is Parliamentary by-elections. There have been four by-elections so far this Parliament and Labour won them all. However, all four by-elections were in seats that were already held by Labour at the 2015 election – three of them by extremely large majorities – so this is again not a particularly positive sign. Governments sometime lose mid-term by-elections, but it is the norm for oppositions to retain their seats in by-elections and nothing to get excited about.

Finally there are local government by-elections – including the bizarre case of Jeremy Corbyn citing a local parish by-election gain in Thanet. Citing local council by-elections is normally a festival of cherry picking – there are a handful or so each week and results vary wildly, so it is simple to pick out only those that paint a positive picture for a party. For example, in the three by-elections last week Labour’s vote dropped by between 7 and 11 percent, the week before the change in the Labour vote varied from a 7 point drop to an 11 point gain. If you take an overall view of Labour’s performance they seem to be holding their own, but not making any significant advance – of the 164 local by-elections so far this year (up to August 11th) Labour have made a net gain of 2 seats.

How deep is the hole?

Looking at Labour position in voting intention polls and their performance in actual elections since 2015 their position is poor rather than terrible. Putting aside Theresa May’s honeymoon bounce, running a few points behind the Conservatives is far from good, but better than the sort of horrific polling that the Tories endured in the nineties and early noughties. These are not the polling figures of a party on course to win the next general election, but neither do they point to imminent extinction.

Equally, while attempts to spin Labour’s mid-term election results as positive are unconvincing, so are claims they are uniquely terrible. They are on a par with the performance of the opposition under Iain Duncan Smith or Ed Miliband.

In terms of public support Labour’s current position is poor, but not exceptionally so. Should the Parliament run until 2020 there would normally be time for them to turn things around. The problem is how they do it. Labour’s polling on underlying questions like leadership and the economy should be far more worrying for them – their ratings there are terrible. Furthermore, for as long as they are hamstrung by internal fighting, there is no obvious way for them to improve them.

The purpose of this article isn’t to apportion blame – when a leader is at war with the MPs is it the leader’s fault for failing to lead, manage and win their support, or is it the MPs fault for failing to back the leader? It takes two to have an argument. I’m also deliberately not suggesting Labour would or would not do any better under Owen Smith (given how little known Smith is to the general public I am deeply sceptical about any polling evidence along those lines… besides, we don’t know what would happen with the left of Labour and all those new members if Jeremy Corbyn was removed)

My own view is that Labour’s current position in the polls is poor, but that it doesn’t show the full extent of their problems. Polls are, as ever, only a snapshot. They could get better… or they could get worse. What happens if Labour’s internal warfare drags on for another four years? What happens if there are defections, deselections, a split? How does Labour put across its message with most of its known faces refusing to serve? How on earth would Labour fight an election in this state? The root of Labour’s problem isn’t with the wider public, it’s within itself.

Photo: PA