Can well-off pensioners help with the rising costs of social care for the growing minority who need it but can’t afford it?

As a public policy challenge, social care is one of the most fraught facing the government. As we live longer, more of us will need it. How should we pay for it? Should the state raise taxes to help everyone – or keep taxes down and insist that people pay for as much of their own social care as possible?

However it is no less awkward as a personal prospect for people who have not yet retired, as they contemplate the perils of what to do if they can no longer live independently. YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect finds that our views are informed by a remarkable chasm between two sentiments: the first is that today’s over 70s are generally regarded as comfortably off by their own children; the second is that many of those same children fear that they, themselves, will fall off a financial cliff should they need help in their later years.

This fear may explain why, along with recent horror stories in the media, so few of us fancy the idea of ending up in a care home. Only one per cent of us say this is what we want if we can no longer look after ourselves. Put bluntly, many of us are petrified that we could end up both broke and badly treated.

According to the Office of National Statistics, just under 300,000 people over 65 live in a care home. That is three per cent of this age group. Our survey’s figures are consistent with this. We polled 1,199 people under 60. Just under half of them have a parent over 70. Four per cent of these have a parent in a care home.

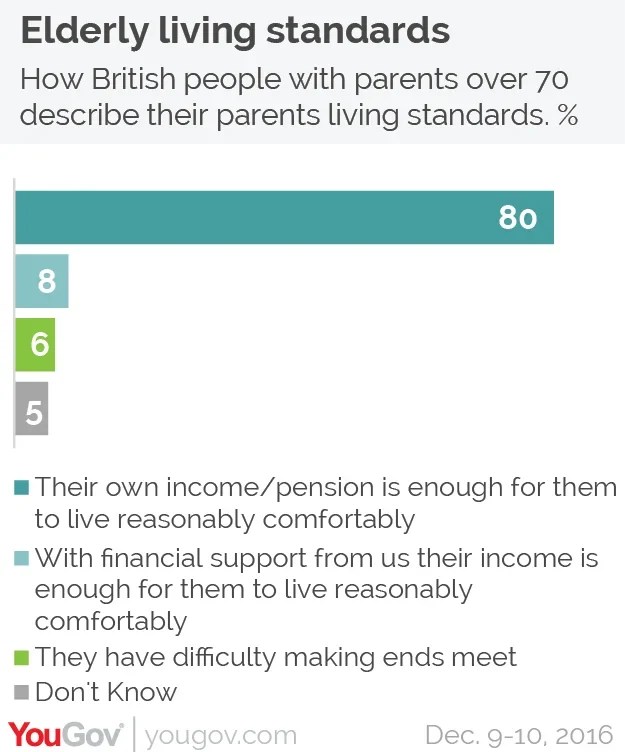

In contrast, fully 82% of these parents live independently in normal housing. Of the rest, the majority live either in sheltered housing or with their children – our respondents. And financially, these over 70s are mostly in good shape. As many as 80% of our respondents say their elderly parents have enough money “to live reasonably comfortably” – a figure that rises to 88% when we include parents who receive financial support from their family.

In contrast, only 53% of all Britons under 60 say that they themselves have “enough to live reasonably comfortably”. Official statistics have recently confirmed that the average income of pensioners has risen significantly more than the national average in recent years. That does not mean the problem of pensioner-poverty is cured. Our survey excludes over 70s without children – they may well face greater challenges, including over money. But the point remains: as long as their own care costs don’t rocket, most older people live reasonably comfortably.

The problems come when we look over the cliff edge. In our survey, just 19 respondents have a parent in a care home. It’s too small a group to be sure of an accurate reading; but it’s a sobering indicator that only seven of them say their parents have enough money to live comfortably.

How, then, do the under 60s contemplate their own old age? Their figures for life expectancy look pretty hard-nosed. Six out of ten expect to live until they are least 80, two in ten until they are at least 90.

We then asked our sample of under-60s how they would prefer to live if they could no longer live independently and had enough money to make the choice. We offered four options.

Three were chosen by broadly equal numbers: at home with a paid carer, at home with the support of the family, or in a sheltered community with care provided. A mere one per cent chose social care.

Had the figure been, say 10-15%, one might attribute the finding to a predictable preference among most people to stick with places and people who are familiar. But I have never seen a personal choice win such little support. It suggests something far closer to dread, as distinct from a reasonable but marginally less attractive option.

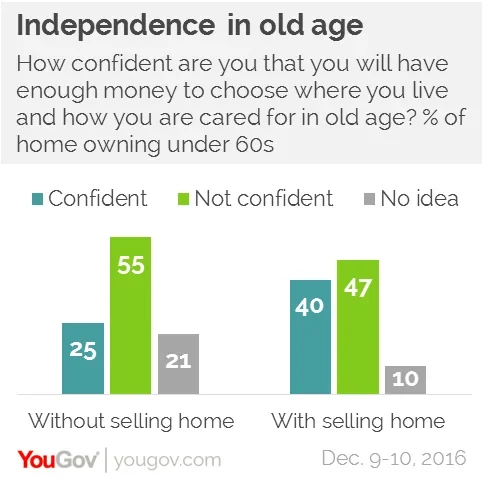

Part of the dread relates to cost. We know that social care is expensive. And only a minority of people are confident that they will have the money to choose the post-independence life they would like to lead. Just one in four home-owners expect to have enough, though the figure almost doubles if they include the cash they would raise by selling their home. That means half of all home owners are either not confident of having enough money, even if they sell their home, or aren’t sure.

The prospects for people who rent are much worse. Only 14% expect to be well enough off to make the choice (and that includes a fair number of younger adults who don’t currently own their own home but expect to do so in future). As many as 68% of renters are not confident they will be able to afford the choice.

This brings us back to government policy. If the cost of caring for older people is going to become increasingly expensive, as life expectancy continues to rise, how should it be funded?

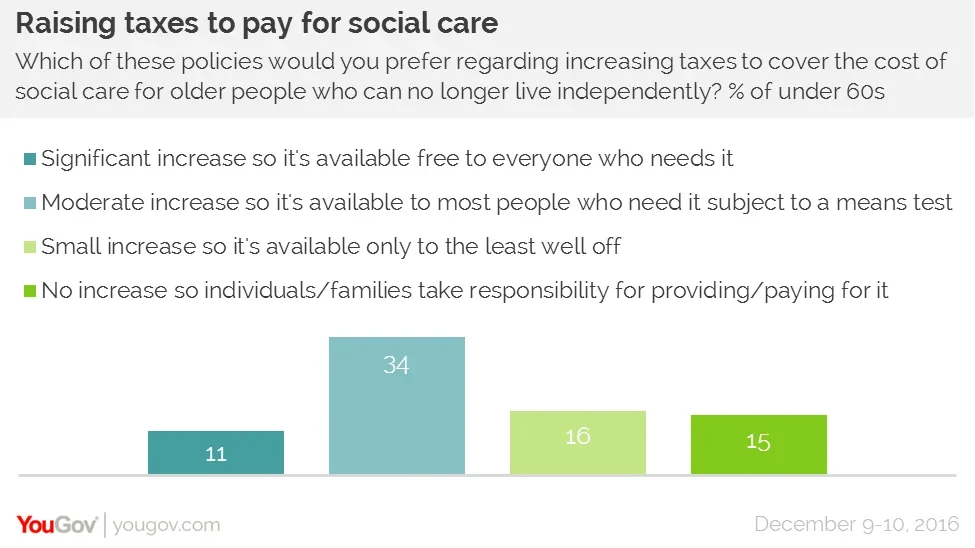

The most popular option is a moderate increase in taxes, so that “subsidised social care is available to most people who need it, subject to a means test”. Of supporters of the four main Britain-wide political parties, only Ukip voters disagree: their most popular option is “no increase in income tax so that individuals and families take responsibility for providing, or paying for, social care”.

As for the vexed issue of whether to force home-owners to sell their home (or borrow against its value) to help pay for their social care, the idea holds little appeal to the over 40s. Only 21% back the idea, while 50% would prefer taxes to rise to allow people to hold on to their housing equity.

The dilemmas facing ministers are clear. The present government has protected many of the benefits for the over-65s from the austerity of recent years. They (actually – interest declared – we) enjoy free prescriptions, winter fuel allowance, free bus travel and a state pension that has been rising faster than wages. Those of us who are still working are exempt from paying national insurance, while the over 75s don’t need to pay for their television licence.

Politically, the thought is perhaps heretical; but in social and economic terms, is there a case for rebalancing the package, so that some of the support for comfortably-off pensioners is diverted to help meet the rising costs of providing high quality social care for the growing minority who need it and can’t afford it?

This commentary appears in the February edition of Prospect

PA image