The ‘In’ and ‘Out’ campaigns for the European referendum are not even formed, but an analysis of the different voting groups they will have to appeal to reveals some major challenges ahead

The referendum on British membership of the European Union is at least a year away, possibly two. As of today, there are not even formal campaign organisations on either side. But a new analysis of 49,903 voters from YouGov Profiles reveals some of the challenges that lie ahead for each side. Here are three key findings.

1. There are more than two groups of voters in this debate

Many voters do not yet have an opinion at all on the EU referendum question, and this group will be the hardest fought over when the campaign comes. But even among the people who do have an opinion, the firmly-decided on each side have very different characteristics to the voters who are leaning one way or the other but still 'in play' for both sides.

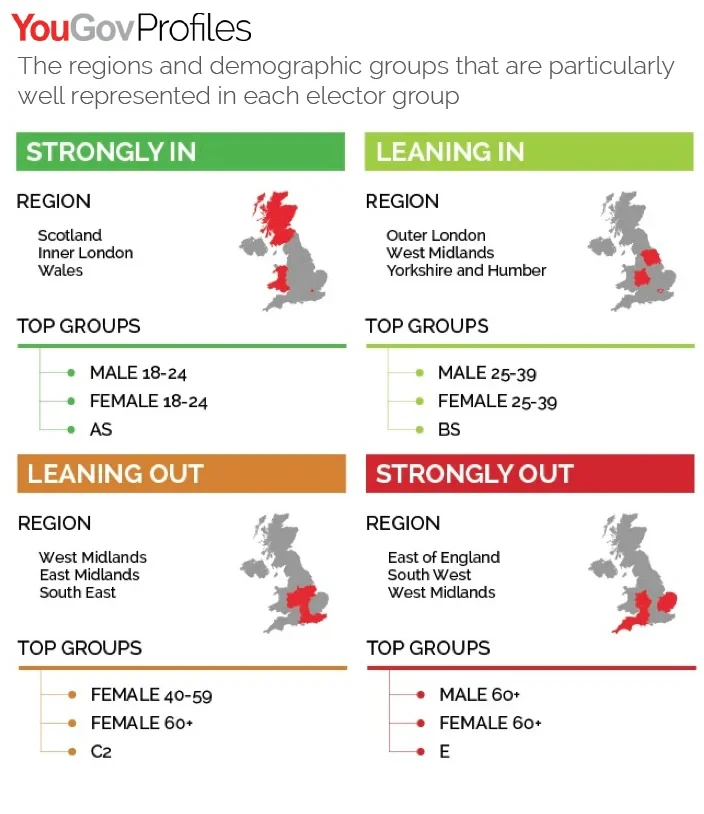

Looking at these as four groups instead of two, and scanning for the attributes that make them distinct, you see that they are particularly dominant in different demographic groups and different areas of the country. For each campaign, most of the voters who are already decided are in the bag – the challenge will be to shore up the votes that are so far only leaning, without alienating the core.

2. The attitudes of definite ‘inners’ are totally different to leaning ‘inners’

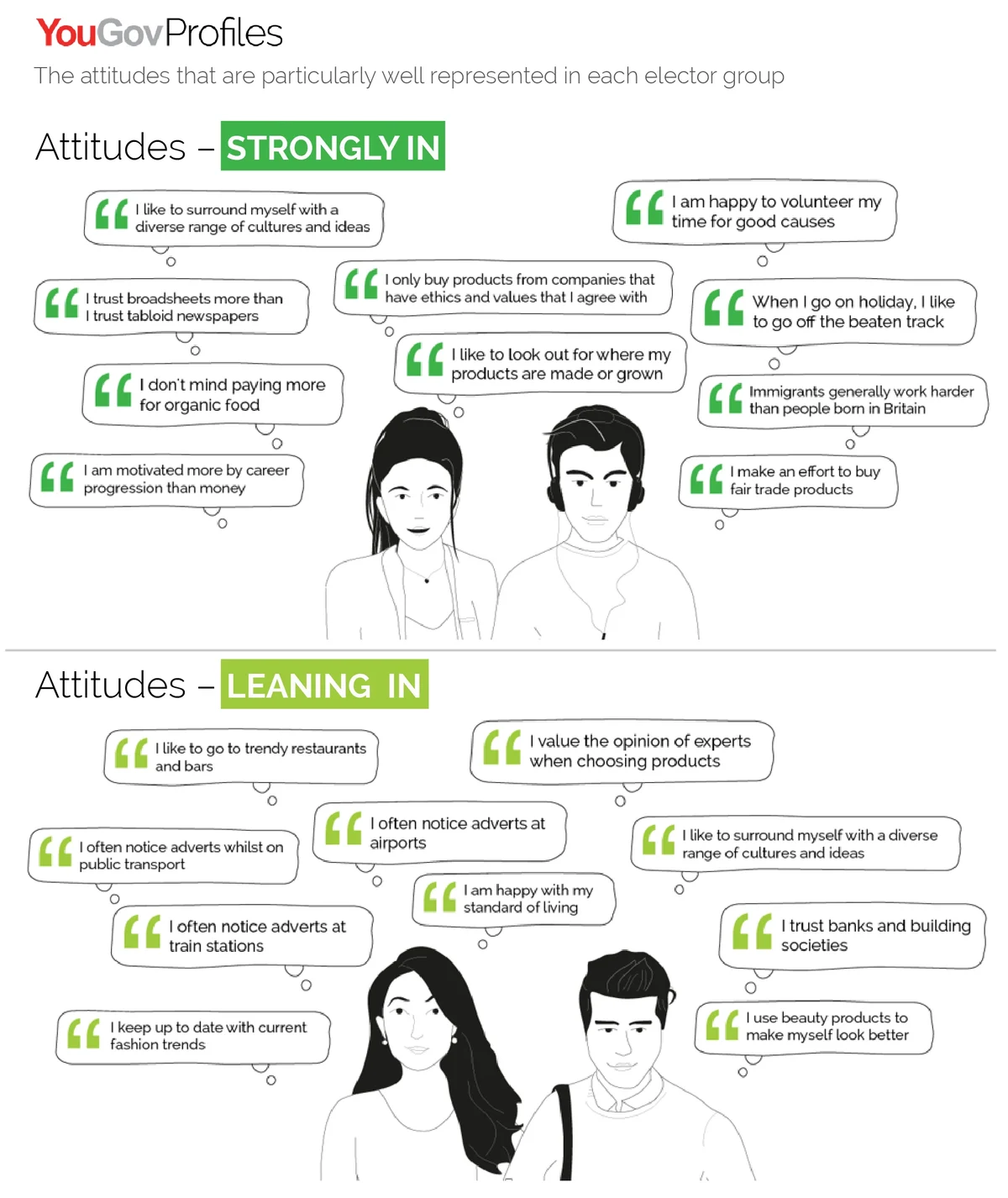

All members of YouGov are regularly presented with attitudes and asked whether they agree with them or not – we use over 300 statements covering everything from politics to shopping and thoughts on life. If you identify a group such as one of these elector groups, YouGov Profiles can reveal which attitudes are disproportionately popular in that group compared with everyone else. It is a fascinating way of learning about a group of people without asking them any new questions.

The graphics below show the top ten over-scoring attitudes in the strongly-in group and the leaning-in groups. What is instantly clear is that they are strikingly different types of people, who will respond to very different campaign messages.

From their attitudes, the "definite inners" seem to be defined by a high-minded internationalist spirit, strongly ethical and progressive. This is a group that is asking to be inspired by the political project of Europe, by Britain’s diversity and its place in the international order of the future.

Next to it, the top-scoring attitudes of people who are only leaning in seem very different. Firstly, politics is nowhere to be seen: this is not a group that is defined by its political opinions. The attitudes that define them are primarily aspirational, and connected with lifestyle. They are receptive to advertising, keep up with trends and crucially are happy with their standard of living. To appeal to this group you can see an entirely different campaign taking shape, based on the practical benefits of being in the EU, and its importance to Britain’s economy.

The danger within each campaign will be to give too much influence to the evangelists on each side, instead of aiming the messages at the harder-to-reach, less politically engaged voters that will end up deciding the outcome.

3. Like it or not, David Cameron has the most powerful voice

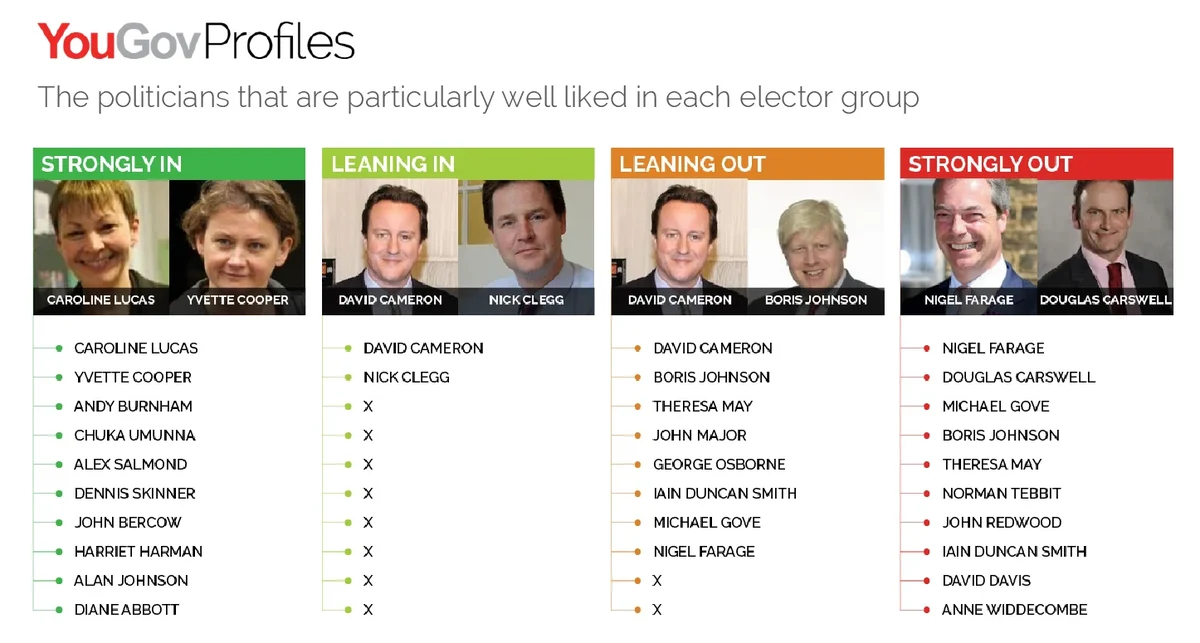

No doubt the campaigners on both sides of the referendum question will be keen to keep it away from the government. David Cameron himself may hope to keep away from the campaign front line. But an analysis of which politicians each group disproportionately likes compared to the rest – ie the people who should be delivering these messages if the campaigns hope to cut through – shows that David Cameron occupies a powerful place.

Looking at the chart above, to the left are the politicians more favoured by definite ‘inners’ – headed by Caroline Lucas, it’s a roll call of pin-ups of the political Left; to the right, most favoured by the definite ‘outers’, are most of the expected names of the Eurosceptic establishment.

More interesting are the names – or lack of names – among the voters who are not yet sure. The ‘leaning in’ group only show two political figures as disproportionately popular – David Cameron and Nick Clegg. These are surely the voters that won the Conservatives the general election: busy, practical, and not particularly interested in politics. No other names even cut through. The fact that Mr Cameron also tops the list for the group that is leaning ‘out’ doubly underlines the power that his voice will carry in the campaign ahead.

The most valuable voters on each side are the ones least interested in politics, and no matter what the die-hards on either side will say, these people will be disproportionately receptive to the pragmatic authority of the prime minister.