Sunday's Labour lead could turn out to be a blip, but David Cameron has work to do either way

David Cameron may regret his decision to debate with Jeremy Paxman rather than Ed Miliband. The first full survey since that television encounter shows Labour moving to a four-point lead, with viewers now saying Miliband won the contest.

YouGov’s poll for the Sunday Times indicates a swing of more than 6% from Conservative to Labour across England and Wales. If this were repeated in every constituency, Labour would gain enough seats to come close to an outright majority, even if it loses badly in Scotland. Labour would end up with 314 MPs and the Tories 251, followed by the SNP (48) and Lib Dems (16).

However, past experience suggests that many MPs defending marginal seats will enjoy an incumbency bonus. Taking this into account, I estimate that our overall figures would give Labour 289, Conservative 267, SNP 43 and Lib Dems 28. Ed Miliband would certainly become prime minister, but would either need allies, or live precariously from week to week, and probably seek an early second election.

Thursday night’s television performance – and, at least as important, media coverage of it – has done Miliband a power of good. Initial snap polls by YouGov and ICM pointed to a narrow Cameron win. Now, as the dust settles, voters make Miliband the clear victor.

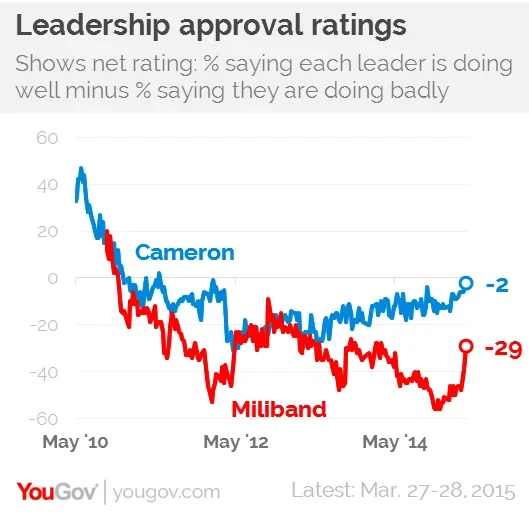

This has helped Labour’s leader climb to his highest rating for more than a year. He is still in negative territory, on minus 29 (with 30% saying he is doing well and 59% badly), but this is a marked improvement on his minus 48 rating earlier this month.

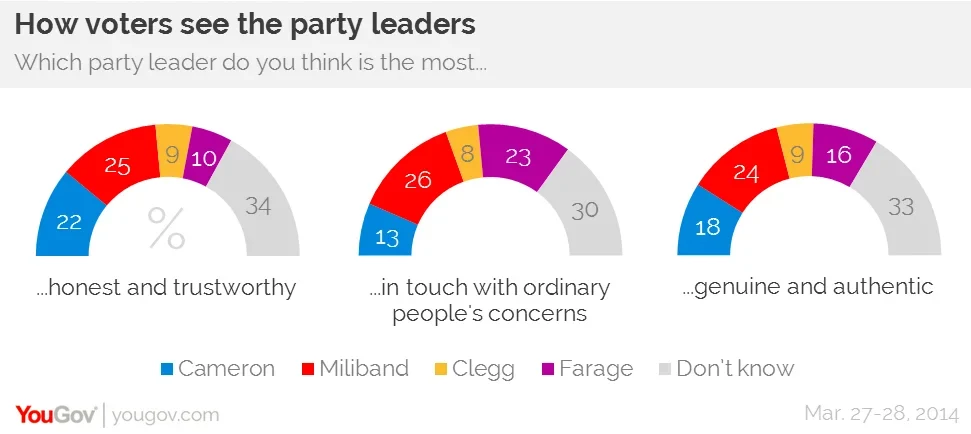

Milband still lags David Cameron (minus two this weekend), but he enjoys some real advantages. In an era when voters think most politicians are up to no good, he is seen as more trustworthy, genuine and in touch than Cameron. If the coming election were decided by likeability, he would win comfortably. He now needs to show that he has the makings of a national leader.

He must also persuade many more voters that Britain’s economy would be safe in his and Ed Balls’ hands. One option is to exploit a specific Tory weakness. Despite the recent rise in real wages, few people feel better off than they did five years ago. If Miliband can frame the coming campaign as a “living standards election”, he might be able to win over some of the floating voters he needs – especially as Labour enjoys a 24% lead over the Conservatives on the NHS, which our poll finds is the public’s top priority.

On the other hand, Sunday’s Labour lead might prove to be a short-lived blip. Cameron remains the favoured prime minister; and the Conservatives are still far more trusted than Labour to run the economy. With that double advantage, the Tories must hope they can overtake Labour between now and May 7. They need only a modest swing back to end up as the largest party.

Their challenge is to tackle the two big factors that are holding them back. The first is that while voters give the government high marks for reviving the economy and reducing the deficit, they reckon that ministers have failed on every other front: health, immigration, crime and education.

Cameron could try to repeat what John Major did successfully in 1992: stress that rising living standards and improving public services need a strong economy. This way, the prime minister might be able to turn an argument about empathy with normal voters, which he is likely to lose, into a debate about competence, which he might win.

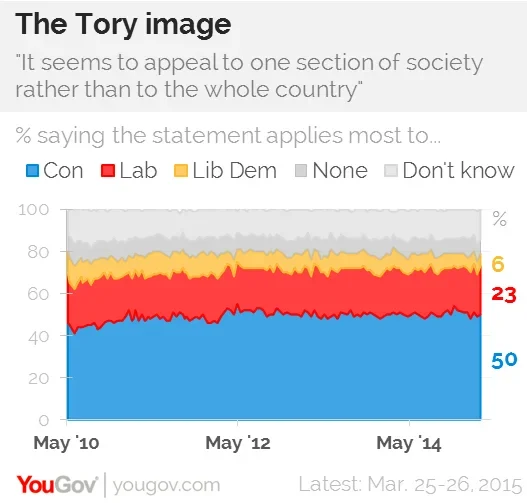

The Tories’ second challenge flows from this. Millions of voters see them as a party of the rich, out of touch with their lives and problems. One recent YouGov survey found that 50% blame his party for “appealing to one section of society rather than the whole country”. That figure has scarcely shifted – in fact it is fractionally up – over the past five years. This is despite such measures as taking low-paid workers out of tax. The bedroom tax, stories about the party’s hedge fund donors, and the cut in the top rate of tax are thought to reveal its true colours.

To burnish the Tory brand, Cameron must persuade voters that it truly believes in fairness, and not just in throwing crumbs to the less well-off. Forty years ago, Labour’s Denis Healey promised to “tax the rich until their pips squeaked”. Few things would help the Tories more than manifesto promises that provoked squeals of anguish from some of their well-heeled allies.

What if the efforts of each party fail – or cancel each other out? There is a real prospect of a messy result that makes coalition-formation exceedingly difficult.

I would not be surprised if we ended up with a minority single-party government. In March 1974, Labour won four seats more than the Conservatives, but could not reach a majority even if they did a deal with the Liberals. Harold Wilson formed a minority government, put forward his programme and challenged the other parties to vote him down. Together they had 33 more MPs than Labour, so could have precipitated an immediate second election.

They backed off. In the key vote, on the Queen’s Speech, the Tories and Liberals abstained. Only the SNP voted against Wilson. He won by 294-7, one of the largest majorities in recent times for such a vote. Labour then governed comfortably through the spring and summer before calling another election.

Depending on who ends up leading the largest party this May, Cameron or Miliband might copy Wilson’s example and head a minority government for some months. The losing party is likely to be engulfed in a battle over its own leadership. Even if its leader hangs on, it – and the Lib Dems – might fear to bring down the new government straight away. They know that voters are likely to punish political leaders who tried to dodge defeat by paralysing British politics with tactics that looked negative and destructive.

Just as Labour took more than a decade to recover from the public sector strikes that gave us the winter of discontent in 1979, no sensible party would want to be blamed for years to come for provoking a summer of discontent in 2015.

This commentary first appeared in the Sunday Times