Despite poor media coverage, internal splits and poor leader ratings, Labour’s support is currently at around the same level it was in 2015. This is down to a combination of adding people who will vote Labour because of Jeremy Corbyn and holding on to previous Labour voters despite of him. But the current coalition is unstable and might not hold

Due to the perceived unpopularity of Jeremy Corbyn and the divisions within Labour over the past two years, many went into this election campaign expecting the party’s vote share to fall to historic lows.

However, since the campaign started, the party has actually seen an improvement in the polls and is now back up at around the same vote share as it was in 2015 (although of course, we are still only halfway through the campaign so things may well change again). Our analysis suggests, though, that despite the headline number remaining the same there is quite a lot of churn within the Labour vote, with some voters moving towards the party as others shifted away.

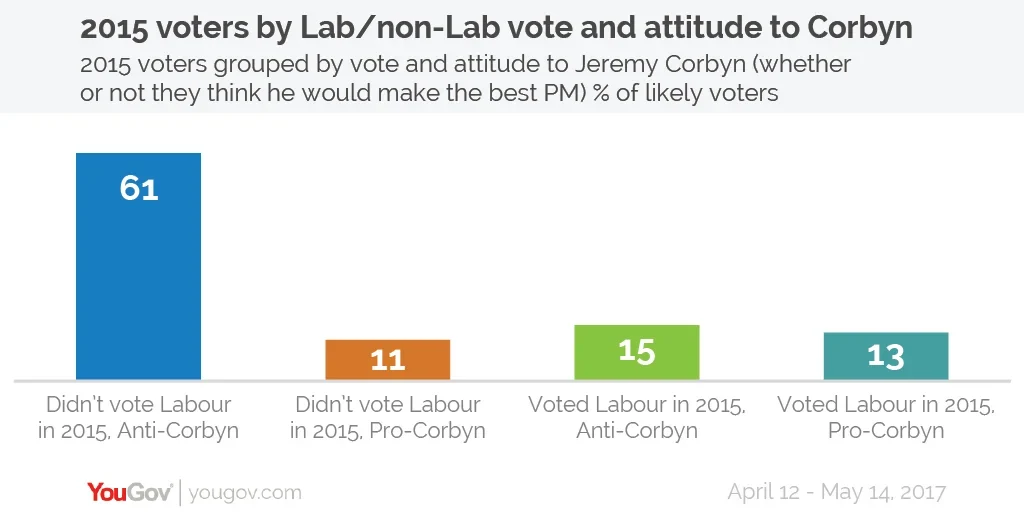

To help explore this in more depth, we have divided the entire British electorate up into four groups based on both their attitude to Jeremy Corbyn and whether they voted Labour at the last election.

There are two groups that are not especially helpful when looking at why the party’s support has improved in the past few weeks – those who think Jeremy Corbyn would make the best Prime Minister and voted Labour last time (13% of likely voters) and those who don’t think Jeremy Corbyn would make the best Prime Minister and didn’t vote Labour last time (61%). The former are pretty solidly Labour and the latter are pretty solidly not.

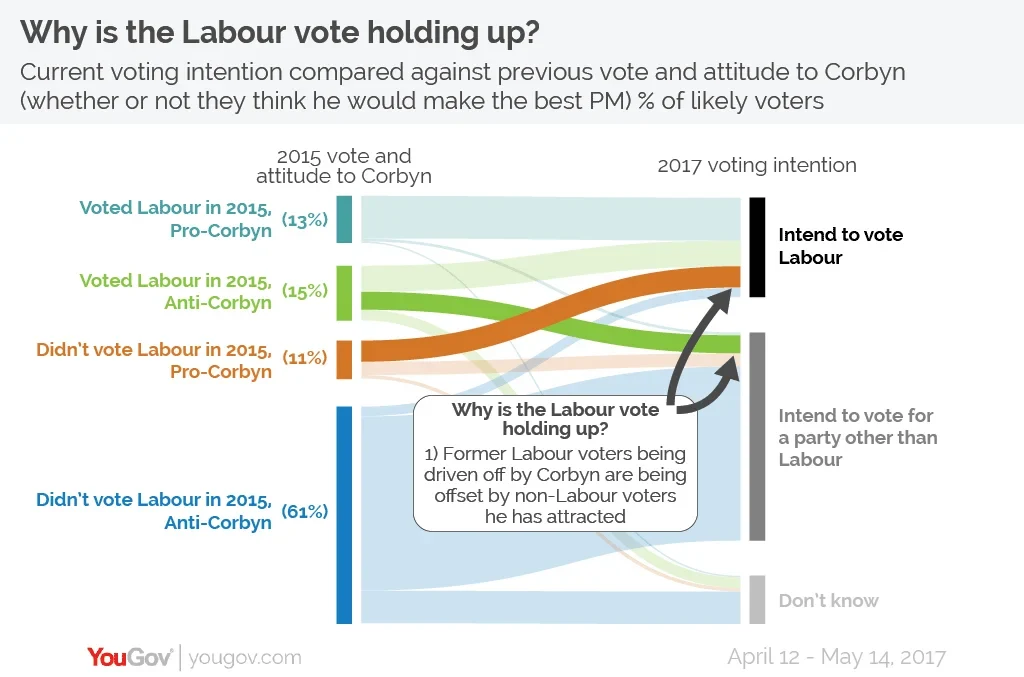

The remaining two groups, however, help us explore the current coalition intending to support Labour on June 8. The first is those that voted Labour at the last election but don’t think Jeremy Corbyn would make the best Prime Minister, which makes up 15% of all likely voters. This is the grouping that accounts for the small difference in polls between the overall levels of support for the party and the support for its leader.

Currently, around six in ten (59%) of this group plan to vote Labour this time around, despite not supporting Jeremy Corbyn. However, a large chunk (41%) have moved away from the party over the past two years.

Yet despite this largescale fragmentation of its past vote, the party continues to maintain its level of support in the polls. This is because the party is gaining a large level of support from those that didn’t vote for them last time but think Jeremy Corbyn would make the best Prime Minister.

Overall this group makes up 11% of likely voters and come from a wide variety of places. Some used to be Greens, some supported the SNP, and many didn’t vote at all in the 2015 election. Overall, six in ten (62%) of them currently say they will vote Labour on June 8. Yet significantly, this group of voters contains many people who are among the least likely to vote – notably young people and those who did not turn out in 2015. While many are enthused by the Labour leader, it may not necessarily translate to showing up on June 8.

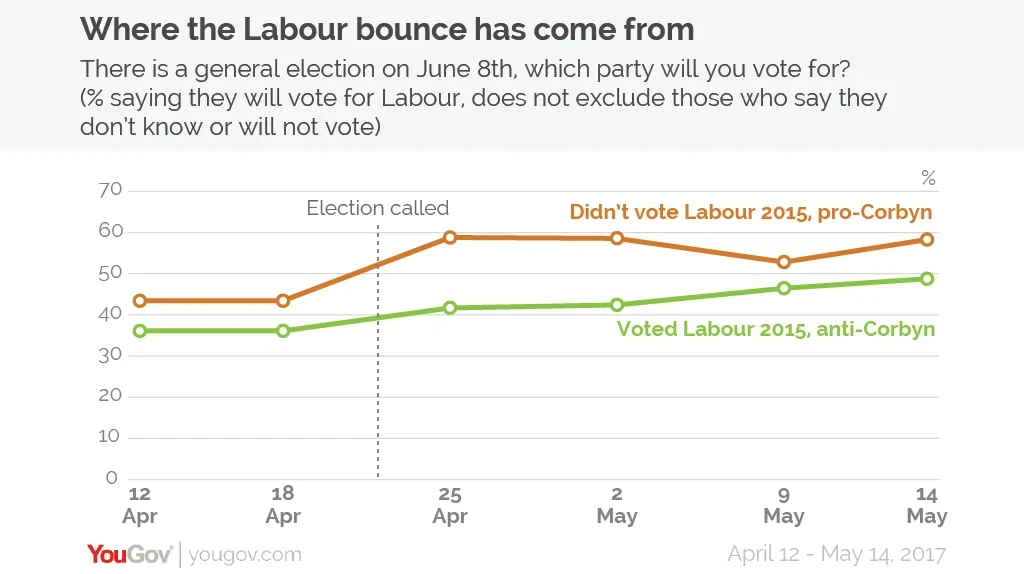

The shift among both the “previously-Labour, anti-Corbyn” and “previously notLabour, pro-Corbyn” segments towards the party is largely responsible for the small “bounce” that it has seen in voting intention polls over the past few weeks. Before the start of the campaign people in both these groups told us they didn’t know how they would vote at the next election. However, since the campaign began, they have slowly drifted towards Labour – meaning the party is back up to about the same levels of support it received two years ago.

By bringing together the minority of the population that think Jeremy Corbyn would make the best Prime Minister, whilst also holding on to many Labour 2015 voters who disagree, this means that currently the Labour vote share is around the same level that Ed Miliband achieved two years ago.

However, while interesting, it shouldn’t give anyone in the party too much cause for celebration. Firstly, polling the same vote share as an election that you badly lost is hardly a resounding achievement. Secondly, even if Labour does hold on to its vote, the rise in the Conservative vote and the collapse of UKIP in many areas means the party will still struggle to hold on in many seats.

Finally, this coalition is heavily reliant on both making sure people who usually don’t vote turn up on the day and making sure a significant number of Labour voters “hold their noses” and stick with the party despite their negative opinion of its leader.

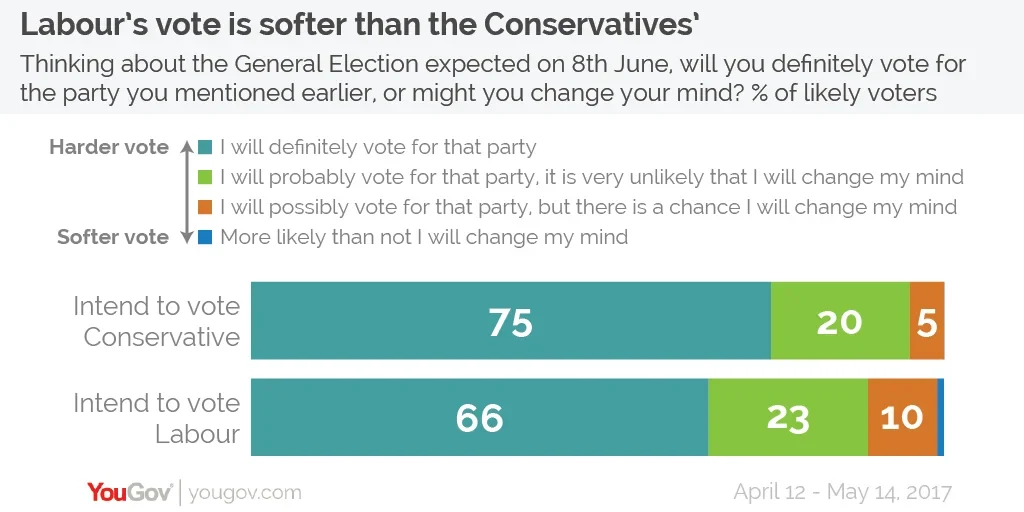

While the former is a perennial challenge to Labour, arguably the bigger danger is that in the final weeks of the campaign, many of those in the latter group might well end up changing their minds in the face of the likely attacks on Jeremy Corbyn by opponents. Indeed, our polling indicates that Labour voters might be more responsive to attacks as they are less likely than Conservative supporters to say they “will definitely vote for this party”.

The extent to which Labour can hold on to these voters is probably going to be the main factor that determines its relative success on June 8. If it can hold together this unstable – and potentially flaky – coalition, it could end the 2017 campaign with around the same proportion of the vote as it got in 2015 (although probably not as many seats).

However, if this group starts to fragment – by either voting for a rival left-of-centre party, or the Conservatives, or by deciding not to vote at all – Labour may still suffer the historic collapse that many have previously anticipated.

Photo: PA