For a great many voters, the side they will end up taking in the referendum will be a verdict on the kind of country we have become and how we got here

Voter stereotypes are often wrong. Forget Mondeo Man and Worcester Women: there was – is – nothing special about them. On most issues, different groups vary less than might be imagined. On taxation, say, or the health service, or welfare reform, there is a large overlap in the views of Mail and Guardian readers, young and old voters, university graduates and those with few qualifications – even Ukip supporters and Liberal Democrats.

Europe is different. A special analysis for Prospect of recent YouGov surveys uncovers unusually deep divisions in public attitudes. For once the differences do match the stereotypes. There is a huge contrast between the kinds of people wanting Britain to stay in the EU and those wanting Brexit.

A separate survey, for Prospect, explores the roots of this division. It finds that voters on both sides agree that Britain’s economic problems are still severe. What divides them is what has caused these problems. But it is a measure of the downbeat mood of the nation as the referendum approaches that, given a choice of 14 EU countries in which to live, including the UK, most of us would pick one of the other 13.

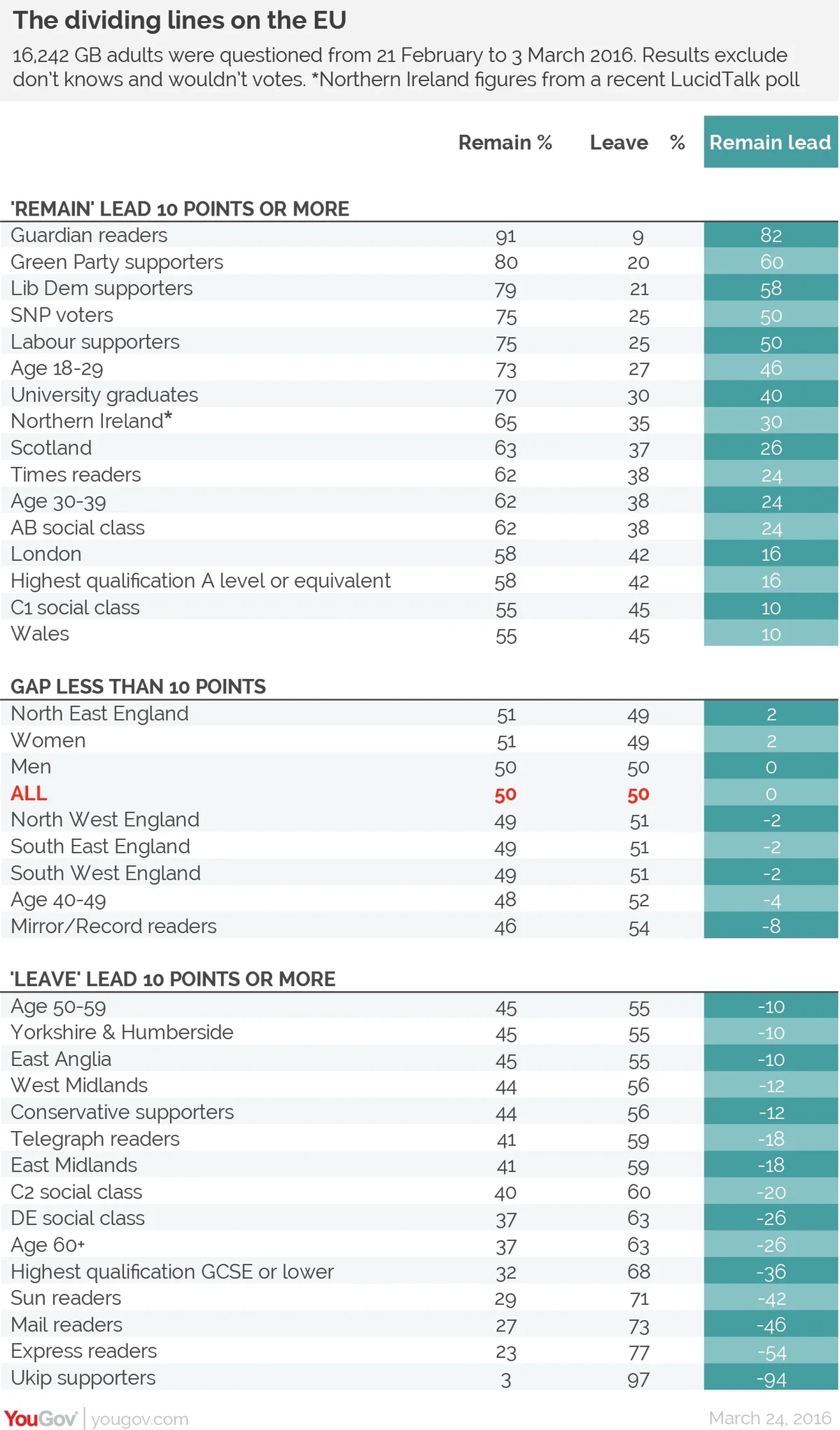

Let’s start with the basic in-out numbers. YouGov questioned more than 16,000 people during the two weeks following the agreement between David Cameron and the rest of the EU heads of government on changes to Britain’s terms of membership. A sample this size allows us to look at sub-groups with some confidence. Overall, our sample splits 50-50 among those who take sides. We detected a modest shift from a slight majority for Brexit at the start of the fortnight to a slight lead in the second week for remaining in the EU. But, overall, neither side has a decisive advantage.

The graphic shows what we found. At one end of the spectrum, 91 per cent of Guardian readers want Britain to remain in the EU, while 97 per cent of Ukip supporters want Brexit. Apart from Ukip, the supporters of all the other significant opposition parties are strongly pro-EU, with 75-80 per cent saying they will vote for staying in. Conservative voters divide 56-44 per cent for Brexit; however, there are signs that the Prime Minister is beginning to win some of them round to the “remain” camp.

One curious, and possibly significant, finding concerns the don’t knows, omitted from our graphic. As many as 21 per cent of Conservatives say they have yet to make up their mind – far more than the supporters of Labour (14 per cent), Lib Dem (12 per cent) or Ukip (4 per cent). This is unusual. Normally, Conservative supporters are less likely to say “don’t know” to questions on public policy. But today, there are two million of them who are torn between the two sides. In a close race they could well be decisive. Will they end up loyal to their party leader and cast a risk-averse vote for continued membership of the EU – or will dislike of Brussels and the appeal of Boris Johnson and other leading Tories propel them to a vote for Brexit?

On the other side of the party fence, the turnout of Labour voters matters hugely. They currently comprise 47 per cent of all pro-EU voters. If Jeremy Corbyn’s reluctance to campaign enthusiastically for the party’s long-established policy causes a significant number of Labour supporters to stay at home, this could be fatal for the pro-EU cause.

Indeed, differential turnout could well decide the outcome. Look at the age divide. Voters under 30 divide 73-27 per cent for “in”, while the over 60s divide 63-37 per cent for “out”. As turnout tends to be much higher among older than younger electors, this is good news for the “out” campaign(s).

On the other hand, university graduates (70-30 per cent for “in”) and people in the professional and managerial AB social class (62-38 per cent) tend to be more assiduous voters than those with GCSEs at most (68-32 per cent for “out”) and semi- and unskilled DE workers (63-37 per cent). So, overall, it is not clear which side, if either, will end up doing better if, say, the turnout is 70 per cent rather than 60 per cent.

If the overall result is very close, then the geography of the vote could have big implications for the UK’s future, whichever side wins. London, Scotland and Wales all currently have clear majorities for “in”. So does Northern Ireland, according to a recent poll by LucidTalk. (YouGov does not conduct political polls in Ulster.) Although unionists divide three-to-one for Brexit, fully 88 per cent of nationalists (and also Alliance and Green supporters) who take sides want to stay in the EU.

Taking the UK as a whole, the aggregate figures are striking: together, London, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland divide 60-40 per cent for staying in the EU, while provincial England – that is, all the English regions outside London – divide 53-47 per cent for Brexit.

Much has rightly been made of a backlash north of the border should Scotland be forced out of the EU by the votes of provincial England; but maybe some thought should be given to the consequence of a narrow “in” majority, in which provincial England is thwarted by a coalition of Londoners and Celts.

One final point from our aggregate analysis. For many years, Rupert Murdoch has been adroit at sensing the mood of his papers’ readers, and siding with them. On this occasion, our figures send him a mixed signal, with Sun readers backing Brexit by 71-29 per cent, but Times readers, by 62-38 per cent, taking a pro-EU stance. Could Mr Murdoch’s two London papers end up on opposite sides – just as the London and Scottish editions of the Sun advocated different parties in last year’s general election?

Now to the attitudes that underpin the in-out division of public opinion. The referendum takes place in the eighth year of austerity politics. Political scientists, unlike those who study physics, biology and chemistry, are unable to do control experiments. If only we could measure public opinion in a separate referendum at the same time in a parallel universe in which Britain is booming after eight years of steadily rising prosperity. Sadly we can’t. We must do what we can with the data that is available.

For this survey we started to explore the impact of austerity politics on the referendum by asking people how big they thought were the “underlying problems” facing Britain’s economy. Last month, I showed how, at a personal level, optimism is on the rise. Voters are increasingly confident about the future prospects of themselves and their family. But our latest survey shows that this has more to do with people feeling better able to navigate troubled waters, rather than the waters themselves calming down. By six-to-one, we think Britain’s fundamental problems are “very” or “fairly” big rather than “very or fairly” small. As significant is the fact that the views of “in” and “out” voters are much the same. So it’s not that pro-EU voters are more optimistic than fans of Brexit.

However, our next question did uncover huge differences between the two sides. We listed ten possible causes of our economic problems and asked people to say which two or three they blame most. The top three picked by the “in” voters are completely different from the three picked by “out” voters:

- For “in” voters, the top three are: British banks, the Conservative-led government since 2010 and growing inequality.

- For “out” voters they are: EU rules and regulations, immigrants willing to work for low wages and the last Labour government.

These findings suggest that voters are becoming increasingly polarised, not just between “in” and “out” or Left and Right, but between two different conceptions of how Britain got into the condition it is in and, therefore, how to escape to a better future.

At the heart of those differences is a simple fact: the top two blame-targets for Brexiteers are outside factors (Brussels and immigrants), while the top three blame-targets for Europhiles are all internal factors. This accords with other YouGov research down the years. Most voters who strongly oppose the EU are also want to pull up the drawbridge between Britain and the rest of the world – not just by stopping the flow of immigrants but also, for example, ending overseas aid. Some leading advocates of Brexit, such as David Davis and Douglas Carswell, preach an alternative internationalism to EU membership, rather than a retreat into isolationism. But few voters want to leave the EU in order to pursue a more open and generous relationship with the rest of the world.

It is not just that “leave” voters are wary of the lands beyond our shores; they also reject a commonly-made argument about Britain’s global influence. We tested four statements about the EU – two positive and two negative – and asked people whether they agreed or disagreed. The statement that polarise voters more than any other was: “Britain has more influence in the world as a member of the EU than it would have outside it”. Eighty-two per cent of “remain” voters agree; the same number of “leave” voters disagree.

Given all these findings, our next question produced a surprise, to me at least. We listed fourteen EU member states and asked people where they would most like to live if they could be guaranteed to maintain their standard of living. Among the public as a whole, just 39 per cent said the UK; 51 per cent said one of the other 13 countries (with Spain the most popular). Those figures are striking enough. However, I expected a big difference between the two sides in the referendum, with pro-EU voters are far more likely to fancy living abroad than those eager to reassert British sovereignty. In fact, the difference is modest, with only slightly more “out” voters wanting to stay in the UK (35 per cent) than “in” voters (45 per cent).

On this, the big differences concern age rather than attitudes to the EU. By almost two-to-one, voters under 30 would rather live elsewhere in Europe than stay here, while most people over 60 want to remain in the UK.

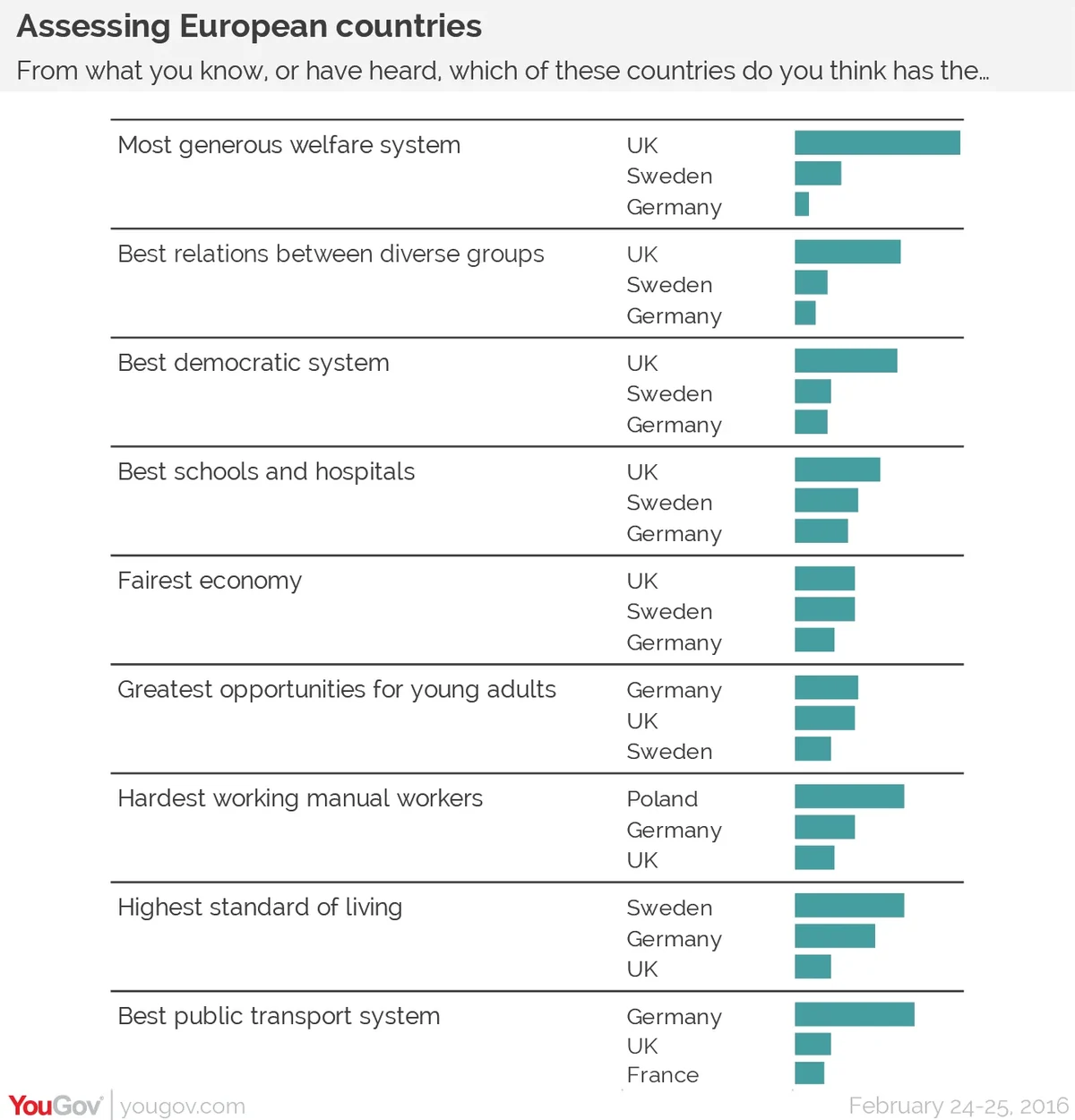

What is it about the rest of the EU that appeals to so many people? We asked people which country was best at doing nine different things, and listed the seven member states on which we reckoned most people would have views. Britain outscored the combined total of its six rivals on three: having the most generous welfare system (50 per cent said the UK; 23 per cent said one of the other six countries); the best relations between people from different backgrounds and ethnic groups (32 per cent; 22 per cent); and having the best democratic system (31 per cent; 24 per cent).

On the other hand, Britain lagged behind other countries on standard of living (Germany and Sweden have higher scores); the best transport system (Germany); and having the hardest-working manual workers (Poland and, again, Germany). In each case there were more don’t knows than normal. However it is clear that many people have a downbeat – or, if you prefer, realistic – view of the state of Britain today.

That may help to explain why so many people would fancy emigrating to the continent if they could be sure of maintaining their living standards. But it doesn’t explain where they want to go. For the three most popular destinations (Spain, France and Italy) all have very low scores when we ask people which is best at doing various things. It looks as if sunshine trumps democracy, economic strength, public services, community relations – and whether we want to leave the EU

Yet in one sense, perceptions of different countries DO influence attitudes to EU membership. By far the biggest difference between the two sides concerns welfare systems. As many as 66 per cent of “out” voters say Britain’s is the most generous, with Sweden (just seven per cent) a very distant second. Among “in” voters, the scores for the two countries are: Britain 37 per cent, Sweden 24 per cent. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that this particular issue provokes feelings not just of national pride, but of a widespread feeling that Britain is a soft touch.

A variety of conclusions may be drawn from our survey; and I doubt we would all agree on what they are. But one big theme emerges. For a great many voters, the side they will end up taking in the referendum will concern not just the terms of the Prime Minister’s agreement with his fellow EU leaders, or the details of our future trading arrangements. It will be a verdict on the kind of country we have become and how we got here.

This analysis appears in the April issue of Prospect.

PA image