Shaun Austin of YouGov and Nic Newman of the Reuters Institute look at what people think about native advertising and what it means for brands and news outlets

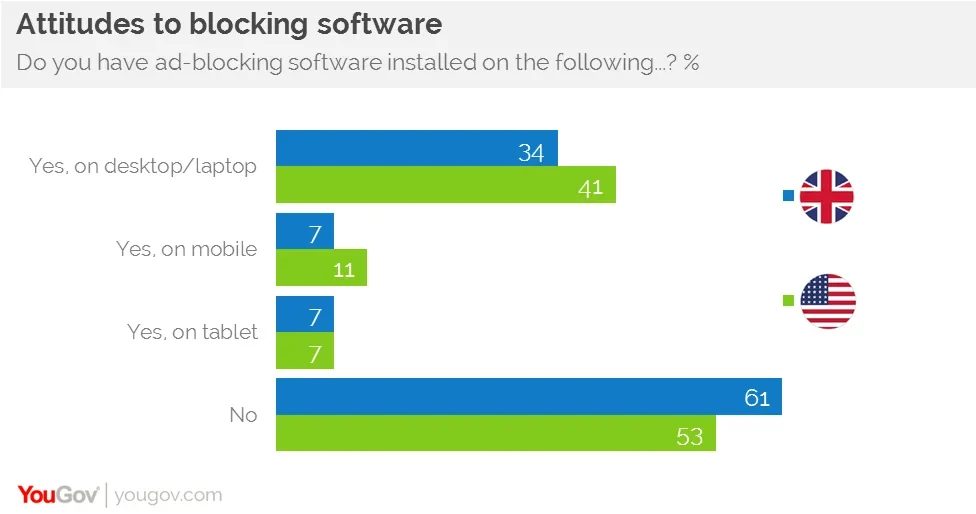

Traditional display advertising on the web is in trouble. Fewer people are clicking on banners, yields for publishers are static or falling, and many users shut off ads completely. YouGov’s research for this report shows that in both the US and UK between a third and a half of online news users use software that blocks the most popular forms of display advertising.

Against this background it is not surprising that content providers, brands, and platforms are looking for new and better ways to reach and engage audiences.

Budgets are switching to so-called ‘native’ advertising where brand messages look more like regular content – sitting in the same templates and using the same formats that might be used for a standard piece of journalism or a user-generated post on social media.

This essay looks at what people think about these new and sometimes controversial forms of advertising. Using survey evidence and focus group interviews in the UK and US we explore consumer attitudes towards this form of sponsored content and the issues of labelling and trust that surround it.

Native advertising explained

Sponsored or branded content is not a totally new phenomenon. Newspapers have been producing advertorials and special supplements paid for by advertisers for decades – but somehow the separation seems clearer in a physical product.

In social media, sponsored posts now sit cheek by jowl with regular updates and content posts. Formats and functionality are identical, labelling is understated and brands are learning fast how to adapt their messaging to be part of a conversation not a broadcast. Facebook and Twitter are building billion dollar businesses on enabling this approach.

New media platforms like BuzzFeed and Vice have also turned their back on display and already make the majority of their money from native advertising formats. They have set up digital commercial teams to develop ‘viral moments’ for brands – articles, lists, infographics, videos, or full-blown web documentaries. In the example here a BuzzFeed list is repurposed to make a fun item for young people around different ways to use tequila in cooking. The item was paid for by Sauza® tequila.

Venture capitalists are investing millions of dollars in companies like BuzzFeed because they have learned to use technology to develop and perfect formats like listicles and quizzes that resonate with internet users of a particular demographic. Effectively, they’ve built world-class systems for content creation, analytics, and advertising.

Over the past year, traditional publishers have been trying to learn from this approach and have set up their own digital studios to do something similar.

The New York Times (T Brand Studio), the Guardian (Guardian Labs), and the Wall Street Journal have invested heavily – in a tacit endorsement of the emerging practice.

In one of the most successful examples to date, the New York Times published a 1500 word native ad for the Netflix series Orange is the New Black, using video, charts, and audio to supplement text about female incarceration in the US. It was one of the first pieces of sponsored content generated by a new T Brand Studio, a nine-person team dedicated to the task.

The Guardian is also creating ‘paid post’ formats as well as pursuing more traditional approaches where journalists create content independently – but still paid for by an advertiser. Unilever paid over £1m for a range of content to be produced on the subject of sustainable living. The section and the articles were clearly marked ‘Sponsored by Unilever’, but in other respects the content melded into the overall Guardian experience.

Definitions and approaches to sponsored and branded content are varied and still emerging. There is no standard approach to labelling and a number of publishers have been caught out, such as when The Atlantic admitted to misjudgements over a Church of Scientology sponsored post. While the IAB has announced some plans in the UK to start rolling out regulations for native advertising and sponsored content, it’s still early days and consumers think more work is needed.

Consumer attitudes

As part of the Digital News Report 2015, we included questions relating to native advertising in the survey for both USA and UK. We followed this up with online focus groups in the same markets to explore attitudes in further detail. In the UK, all respondents were members of our YouGov Pulse panel, our passive web tracking tool. We used web browsing data to select respondents who had engaged with native advertising content, and compared stated attitudes and perceptions alongside actual behaviours of consuming native content.

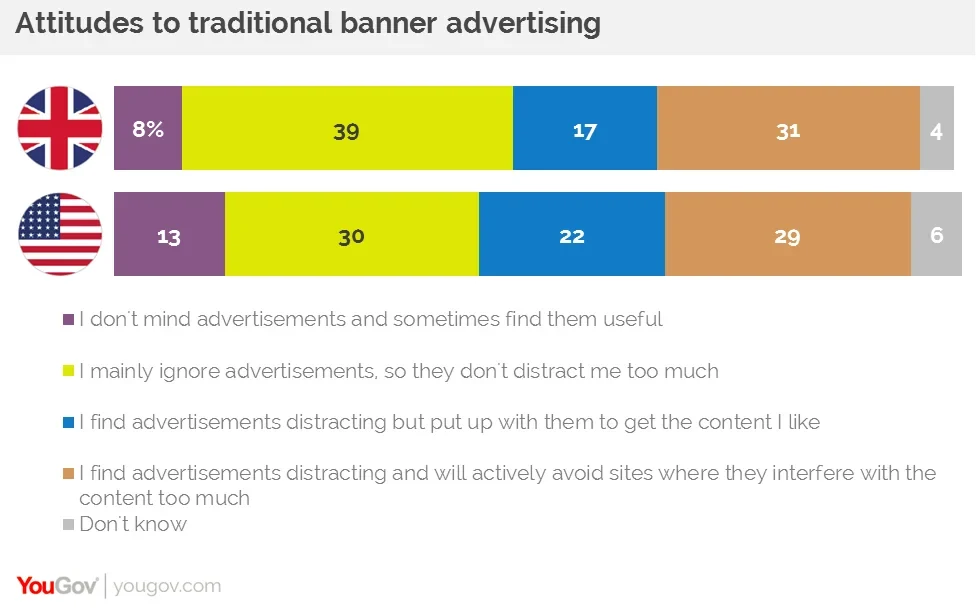

Many consumers are losing patience with traditional forms of online advertising and there seems to be a close relationship between the amount of interruption caused and the vitriol consumers feel towards it. Around three in ten respondents in both the USA (29%) and UK (31%) say they find traditional banner advertising distracting and will actively avoid sites where they interfere with the content too much. Static banner advertising is more tolerable for readers than video advertising, with pop-up advertising being seen as the worst offender of all.

There is also a perception that video advertising impacts on the speed of browsing, which is also particularly frustrating for readers.

Self-playing videos are the devils [sic] creation. You’re browsing the news late at night and suddenly an ad for laxatives is blasting out from your laptop at full volume!

Tanya, 51, UK

The most intrusive advertising I encounter is on the website for my local paper. Huge pop up videos before you can access content. If they weren’t auto playing they wouldn’t be so annoying.

Alan, 31, UK

Pop ups irritate me the most. I don’t like video adverts, but I can live with them because I never willingly listen to them. Banner advertising doesn’t really bother me because I just ignore it.

Helena, 36, UK

Pop ups are most annoying, particularly if you are browsing on a phone as sometimes they can be really hard to close down.

Eleanor, 32, UK

Consumers’ annoyance with advertising and the interruption it causes to their reading experience has led large numbers of them to install ad-blocking software to minimise its impact. In the UK, 39% have installed ad-blocking software on their PC, mobile, or tablet, whereas in the US this rises to 47%. The figures are even higher for 18–24s (56% and 55% respectively).

Many consumers agree that advertising is a necessary part of continuing to get free news. However, the increasing use of ad-blocking software means that advertisers need to find new ways of reaching their audiences, and native content has the potential to reach audiences, particularly younger consumers.

Awareness

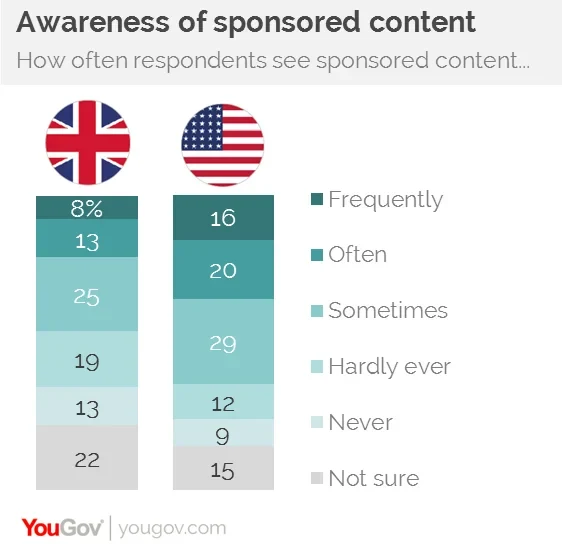

After respondents in the quantitative survey were shown a number of native advertising articles, a relatively high proportion reported having come across this type of content before. In the US, over one in three (35%) said they frequently or often see sponsored content, compared to around a fifth (21%) in the UK.

There is however much confusion over the language around sponsored content and native advertising. For example, one member of our focus group in the US confidently and spontaneously talked about seeing more native advertising. However, once we delved further into it, we found they were actually describing retargeted advertising, based on their browsing history.

Being misled?

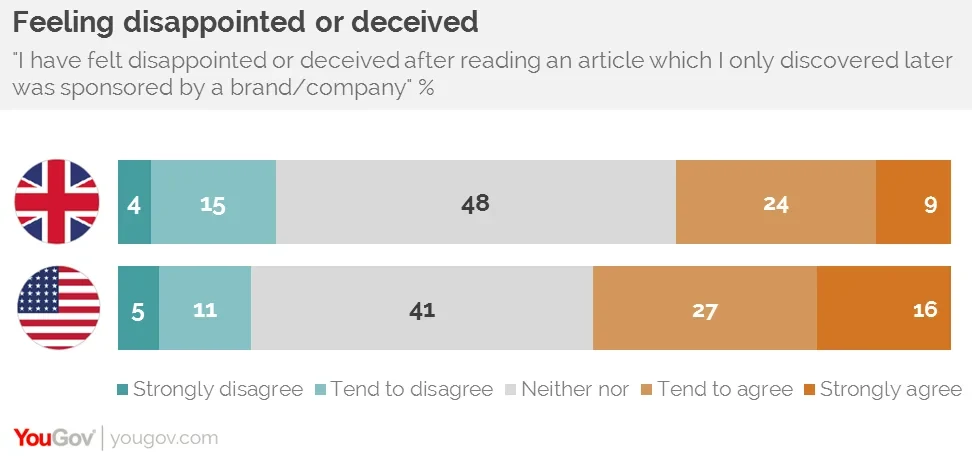

There is a perception that readers are disappointed or feel deceived if they later find out content was sponsored by a brand or company. In the UK, a third (33%) have felt disappointed or deceived, a level that rises to more than four in ten (43%) in the US. The higher figure in the US could be down to the fact that native advertising is more prevalent there.

There are stark differences by age, with younger respondents considerably less likely to feel they are being ‘deceived’ by native content. This is likely to be down to a number of factors. First, they have grown up in a commercial world, with brands firmly ingrained in their lives. Secondly, they are more likely to visit sites such as BuzzFeed, which are considered to be more about ‘fun news’ and therefore a more natural environment for sponsored content. Native advertising is more established and more prevalent on these sorts of sites.

We also found a great deal of inconsistency in the labelling of sponsored content across different news sites, to the extent that frequently readers aren’t aware of what they are looking at before they start reading an article. ‘Paid for’, ‘Sponsored by’, ‘Promoted’ are words used to signpost native advertising content, with some meaning one thing on some sites and another on a different site.

The Guardian website has a page that outlines clearly the definitions of each of the terms it uses, however this is a bit like the ‘terms and conditions’ pages which are rarely read. In order to reduce levels of perceived deception, the industry needs to adopt consistent and clear signposting across different sites if all consumers are to have faith in what they are reading.

The type of content influencing perceptions

With this trust comes a responsibility to ensure that readers are not misled. Many in our focus groups felt that there are some content areas – such as home and world news, politics, and financial news – that should be considered sacred and free from native advertising. These hard lines in the eyes of the consumer are well-illustrated by these responses:

News, politics, finance, for sure [are a no-no for native advertising]. Those are the topics you don’t want people messing with for profit.

Helena, 36, UK, spent around 1.30 minutes reading Netflix/New York Times native advertising

The news press are there also to hold politicians, business and other interest groups to account. If any of them are seen to be influenced by them then they will suffer i.e. HSBC.

Alan, 31, UK, has visited the Guardian Cities site three times over the last year, and spent around 9 minutes on the site

If the news brand wants to be seen as independent and trusted then news, politics, business should not be influenced by commerce.

Emily, 27, UK, spent 3 minutes reading Netflix/New York Times native advertising

I don’t want to see coverage of human rights in Papua brought to me by the companies who make soap out of palm oil.

Tanya, 51, UK

Respondents tell us that, should the brands start introducing native advertising to the more serious news content areas, it would have a damaging impact on their perceptions of the news organisation.

On the other hand, less ‘serious’ areas of news, such as entertainment, lifestyle, fashion, travel, and motoring, are deemed to be more suitable environments for native advertising. This could be due to the fact that brands are already an important part of the landscape in these areas and therefore respondents are more open to hearing from them on these subjects. They also feel that their decisions in these areas may have little long-term impact.

Lying or deceiving me about these topics will have no lasting effects on my life.

Jenn F, 32, US

I think the rule of thumb should be – if the industry is already reliant on advertising (movies, lifestyle, sports, etc.) then it’s OK. But not news and politics. That’s not commercial – or it shouldn’t be.

Helena, 36, UK

I wouldn’t care who wrote it if it was informative and interesting. I would only be annoyed if I read a story and realised it was advertising half way through.

Eleanor, 32, UK, spent time reading Daily Mail/Now TV’s ‘The Warrior Plan: 8 ways to get a body like a Game of Thrones hotty’

Does it hurt news brands or advertisers?

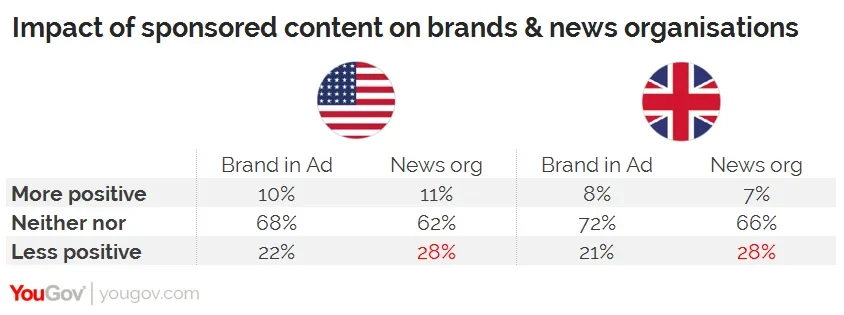

In general, the majority of news audiences say that sponsored content has neither a positive nor negative impact on either the brand in question or the news organisation that carries the content. Around a fifth (22% in US and 21% in UK) say that they have a less positive view of the brand paying for an advert. However, the impact on the news organisation that carries the ad is more negative, with 28% of UK and US respondents having a less positive view of the news brand.

Younger consumers are more open to native advertising on news brands. Almost a fifth (19%) of 18–24 year olds and 15% of 25–34 year olds in the US say they feel more positive towards the brand. In the UK, 13% of 18–24 year olds say they feel more positive towards the brand, a figure that falls to 11% amongst 25–34 year olds. The proportion saying they feel more positive towards the news organisation is slightly lower, but again younger respondents are more positive than older ones.

When talking to respondents in more detail about specific examples, there were significant differences between the UK and the USA. In the US, the reaction to a BuzzFeed article sponsored by Sauza tequila (‘12 Holiday Treats to Spike with Tequila’) was very positive. The respondents thought that the article contained some interesting tips and they weren’t put off at all by a brand sponsoring it. However, in the UK we showed an article sponsored by Renault and the content was perceived to be not really engaging enough to positively impact respondents’ perceptions of the brand. Furthermore, BuzzFeed wasn’t perceived to be a serious news site by these respondents.

However, it was a different story when we showed respondents a New York Times article sponsored by Netflix (‘Women Inmates: Why the Male Model Doesn’t Work’). The reaction from the UK audience was significantly more positive than both their response to the BuzzFeed case study and also the feedback from consumers in the US.

I think this is a very slick looking article. Relevant to the product being advertised but seems to be informative and in-depth.

Alan, 31, spent around a minute reading the Guardian Witness page, powered by EE

The problem is if I see this in the NYT, I assume an editor vetted the article and read it and edited it. Who vouches for the author?

Kathleen, 60, US

Among UK consumers, the New York Times content was perceived to be informative and interesting, while the sponsorship was perceived to be relevant and a good fit. In the US the response was a little more mixed. Some found the content interesting, whilst others felt perturbed that it was advertising dressed up as news – the BuzzFeed example to them wasn’t pretending to be news. In the US, some respondents were surprised to see such content on the New York Times site as to them it is a respected and trusted brand.

One notable example that failed to engage with UK consumers was a content partnership between Unilever and the Guardian. Readers immediately picked up that it had a different tone to the content they would normally expect to see in the Guardian and described the content as bland. This example highlights the need for content to reflect a site’s editorial style and tone in order for readers to find the content engaging and credible.

It feels a little measured, un-noteworthy. It doesn’t feel especially like the Guardian so I suspect someone from Unilever’s ad agency [produced the content].

Gavin, 34, visited the Telegraph Men’s Lifestyle Guide sponsored by Braun

This flags up an interesting paradox. Readers appear to be more engaged with content that replicates the style and tone of the news brand, but as a result, are more likely to feel misled and deceived by the news brand. While news brands have much to gain from this new form of online advertising, the danger of further blurring of the line between advertising and editorial could harm the credibility of news brands, with little lasting impact on advertisers. Consumer attitudes show that, when it comes to native advertising, the stakes are far higher for news brands than for advertisers.

Is the content itself interesting?

Relatively few people say that sponsored content is an interesting way to hear about topics and subjects that are relevant to them. In the UK just 14% like getting information in this way, a figure that increases to over one in five (22%) in the US. It is younger consumers who are more likely to find native advertising content more interesting, although, as mentioned earlier, older respondents are less likely to visit the sites where sponsored content is more prevalent, such as BuzzFeed.

Conclusions

Traditional forms of online advertising are struggling to have an impact. The more it interrupts the reading experience, the more negative consumers’ views are towards it. Therefore brands need to find new ways to communicate with audiences, and sponsored content has the potential to do this; however, the type of content needs to be a natural fit to both the site and readers’ perceptions of the site.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of sponsored content that we found to be of interest to respondents. The first is something practical and/or useful, but potentially more fun (such as the type of content found on BuzzFeed). The second is something that is more serious in nature, is informative, and where there is a clear link between the content and the brand (for example, the types of thing you might find in an online version of a broadsheet newspaper).

However, for broadsheets, native advertising is more of a minefield than it is for entertainment sites. Current affairs, business, finance, and politics sections are generally considered to be sacred by consumers and readers feel that these areas should be free of commercial influence and retain an independent view. Consumers are open to reading sponsored content in areas such as entertainment, travel, fashion, and lifestyle as these are considered to be more appropriate environments for sponsored content.

It is clear that consumers want to see clear labelling and signposting of paid-for content. Readers don’t like to feel they are being deceived; however, if they know up-front that a brand may have influenced the content, consumers are more accepting. To help maintain levels of trust, the language used should be standardised across news sites as much as possible.

Sponsored content has great potential for brands to reach audiences, particularly younger consumers. But whoever brands are trying to reach, the content has to be of value to the audience to have an impact. The content also needs to be a natural fit for the publication – anything that jars with a consumer’s perception of what should be on a site may be dismissed by readers. If these principles can be followed, then sponsored content has a chance of being embraced by online audiences, allowing brands to overcome some of the issues that readers currently have with online advertising.

Juliet Tate contributed additional research to this essay.

For further information on YouGov's YouSay video vox pops, please click here

This essay originally appeared in the 2015 Reuters Digital News Report