Initially, Ukip was a far greater threat to the Tories – but since early last year, for every nine votes it has taken from the Conservatives it has taken six from Labour

Whatever the result, this week’s by-election in Rochester and Strood will qualify for that over-used adjective, historic. If the Conservatives win, Ukip’s bubble could burst – or, at any rate, acquire a slow puncture. If, as seems more likely, Mark Reckless holds the seat under his new colours, then the metaphor changes from bubble to bandwagon, and continues to roll.

It’s a good time, then, to explore the Ukip phenomenon. As recently as March 2012 it had just 5% support and was stuck firmly in fourth place. Now it averages 16% and has easily supplanted the Liberal Democrats as Britain’s third party.

Much has been claimed about the source of its support: at one extreme, it is said to divide the right-of-centre vote and crucify the Conservatives. At the other extreme, Nigel Farage claims it is now taking as many votes from Labour as the Tories.

To delve into what is really happening, I have compared the profile of Ukip’s support in January last year with last month. By aggregating all of YouGov’s voting intention polls for a month, we obtain large enough samples to explore the party’s supporters in some detail. In January 2013, Ukip had started its climb: it had 9%, and was snapping at the heels of the Lib Dems. That month 3,151 people told us they would support Ukip. The figure for our latest monthly aggregate, for October, is 5,701.

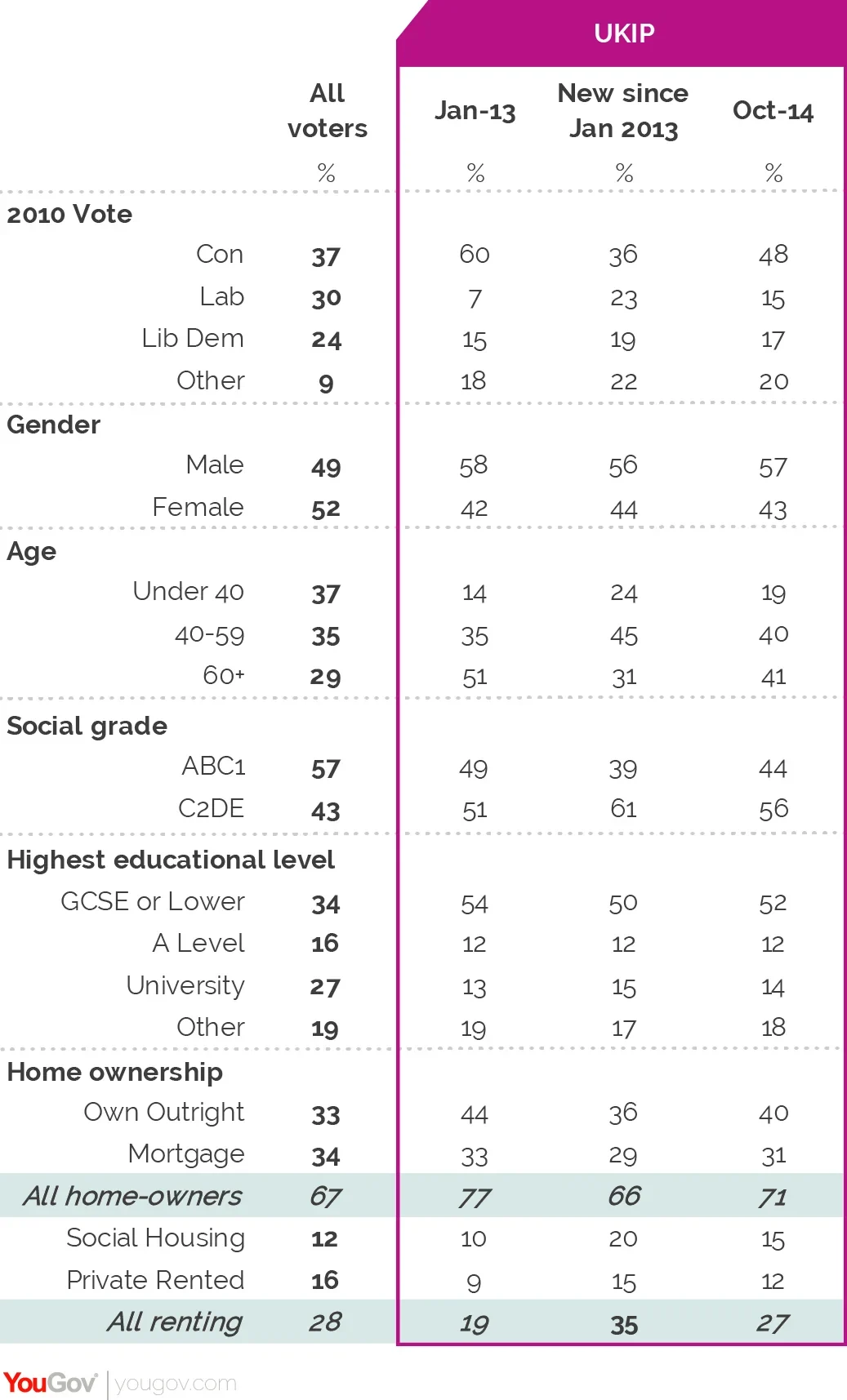

The second and fourth columns of the table below show Ukip’s voter profile for those two months. The first column shows the figures for all voters. The third column sets out my estimate of the profile of the more recent Ukip converts – the extra voters it has won over to take its support from 9% to 16%.

To arrive at these figures I assume that the overwhelming majority of the initial 9% are still Ukip supporters. In the nature of things there will have been some slippage: some voters will have died; and, as a result of normal political churn, some will have swum against the Ukip tide and departed for other parties. But I assume that the great majority of Ukip’s January 2013 supporters remain with the party, and that its current 16% can broadly be divided into two blocks of 8%: those who were already Ukip supporters at the beginning of last year, and those it has gained since then. (Alternative assumptions, such as 7% ‘early’ supporters and 9% ‘recent’ converts, will change the numbers but not the broad conclusions.)

When we apply my 8%-8% assumption, we obtain the figures in the third column below. We can then compare the two groups of Ukip supporters.

In two respects, there is little difference between the ‘early’ and ‘recent’ groups:

- Both are substantially more male than voters as a whole

- The educational profile of the two groups is similar: far fewer graduates than among voters generally, and many more people who never progressed beyond GCE or GCSE – or did not even get that far.

However, in other respects, there are substantial differences.

- As many as 60% of ‘early’ Ukip supporters voted Conservative in 2010. The figure for more recent converts is just 36%, much the same as the voting public as a whole. The proportion of Ukip voters coming from the Labour party has trebled from 7% to 23%. Politically, ‘recent’ Ukip converts look much more like the electorate as a whole than ‘early’ converts.

(To take a different route to the same conclusion, since the beginning of last year, the proportion of 2010 Conservatives switching to Ukip has risen from 14% to 20%, while the figures for the other two main parties are: Labour, up from 2% to 8%; Lib Dems 6% to 12%. With all the parties, the increase since January last year has been exactly the same: six percentage points.)

- The age profile of more recent switchers is also much closer to that of the wider electorate. Ukip still underperforms among the under 40s, who supply 24% of its more recent converts, compared with 37% for the electorate as a whole – but that 24% is a marked increase on the 14% it was achieving when its support first started to climb two years ago. And whereas fully 51% of its initial surge came from people over 60, that figure is down to 31% among more recent converts, which is very close to the national average of 29%.

- Linked to age, there has been a shift in the pattern of Ukip support by housing tenure. Early supporters were far more likely to own their homes outright, and far less likely to rent privately. This is what one would expect when you have more than three times as many supporters over 60 than under 40. As Ukip voters have become younger, so fewer of them are outright home-owners and more of them rent privately.

- On the other hand, when it comes to social class, Ukip’s support has become LESS representative of the electorate as a whole. These days, 43% of Britain’s voters are working class. Ukip’s initial support was already tilted that way, with 51% working class. The figure for recent converts is much higher: 61%.

All this is consistent with European, local and by-election results this year. Ukip is now building support in traditional working-class Labour areas. Initially, Ukip was a far greater threat to the Tories, for it took nine votes from the Conservatives for every vote it took from Labour. Since early last year, for every nine votes it has taken from the Tories it has taken six from Labour.

That said, I would be surprised if Ukip captured many seats from Labour next May: Grimsby, perhaps, and just possibly Rotherham. Labour’s real problem is that Ukip might establish itself as the clear challenger in dozens of Labour seats across the North, with a chance of squeezing the residual Tory and Lib Dem votes in 2020, and defeating a number of Labour MPs in that election.

In 2010, most Labour MPs – 145 out of 258 – came from Scotland and the north of England. Unless the party can start to win back more of its traditional supporters, it faces losing a sizeable chunk of its heartland seats over the next two elections to the SNP and Ukip. That’s not – yet – a prediction, but it is a real possibility.

As for next May, the intriguing question is whether Ukip’s support will fall back – and, if it does, how many of which groups of supporters will it lose? If it holds on to its early voters and loses its more recent converts, this will not help the Conservatives much. But if the Tories can win back the voters who deserted them when the economy was flat on its back, especially in the Conservative-Labour marginals, then Cameron stands a real chance of leading the largest party in the next House of Commons.

Seldom have the future contours of British politics looked less certain. Nobody can be sure whether the SNP and Ukip will produce electoral earthquakes, or whether this autumn’s Scottish referendum and Ukip by-election triumph(s) will prove to be the twin peaks of insurgency, after which things return to normal.

Which will happen? Ask me again next year – on May 8.