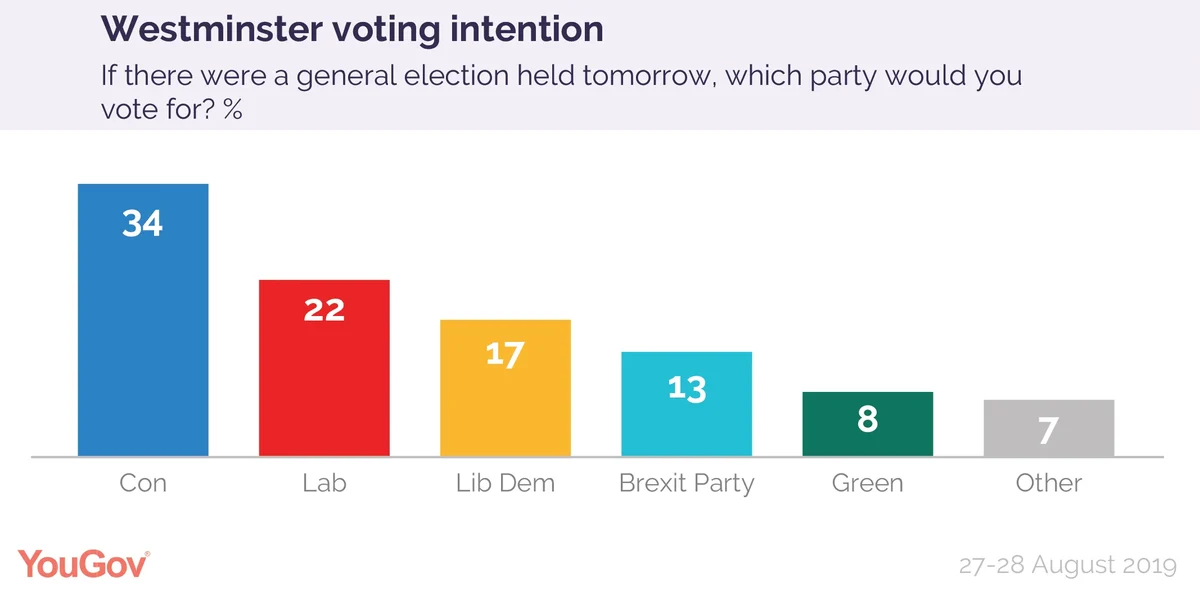

YouGov figures show the Tories have a 12-point lead. But a united remain front and tactical voting could topple them.

The latest YouGov polling results will have been warmly received in Downing Street. Not because the Conservatives are polling particularly well – in fact, if they were to finish an election on their current 34% it would be one of their worst results since the second world war – but because they are 12 points clear of Labour.

The main reason for the Conservative lead is that the leave vote is fairly united, while the remain vote is deeply divided. The majority (53%) of leave voters say they will vote for the Conservatives, while the remain vote is split between the Liberal Democrats (32%), Labour (32%) and the Greens (12%). And the first-past-the-post electoral system punishes division. While the Conservatives face losing a handful of seats to the Lib Dems in the south and the SNP in Scotland, they would currently be more than offset by big gains in Labour/Conservative marginal seats (such as Canterbury, Bedford and Battersea).

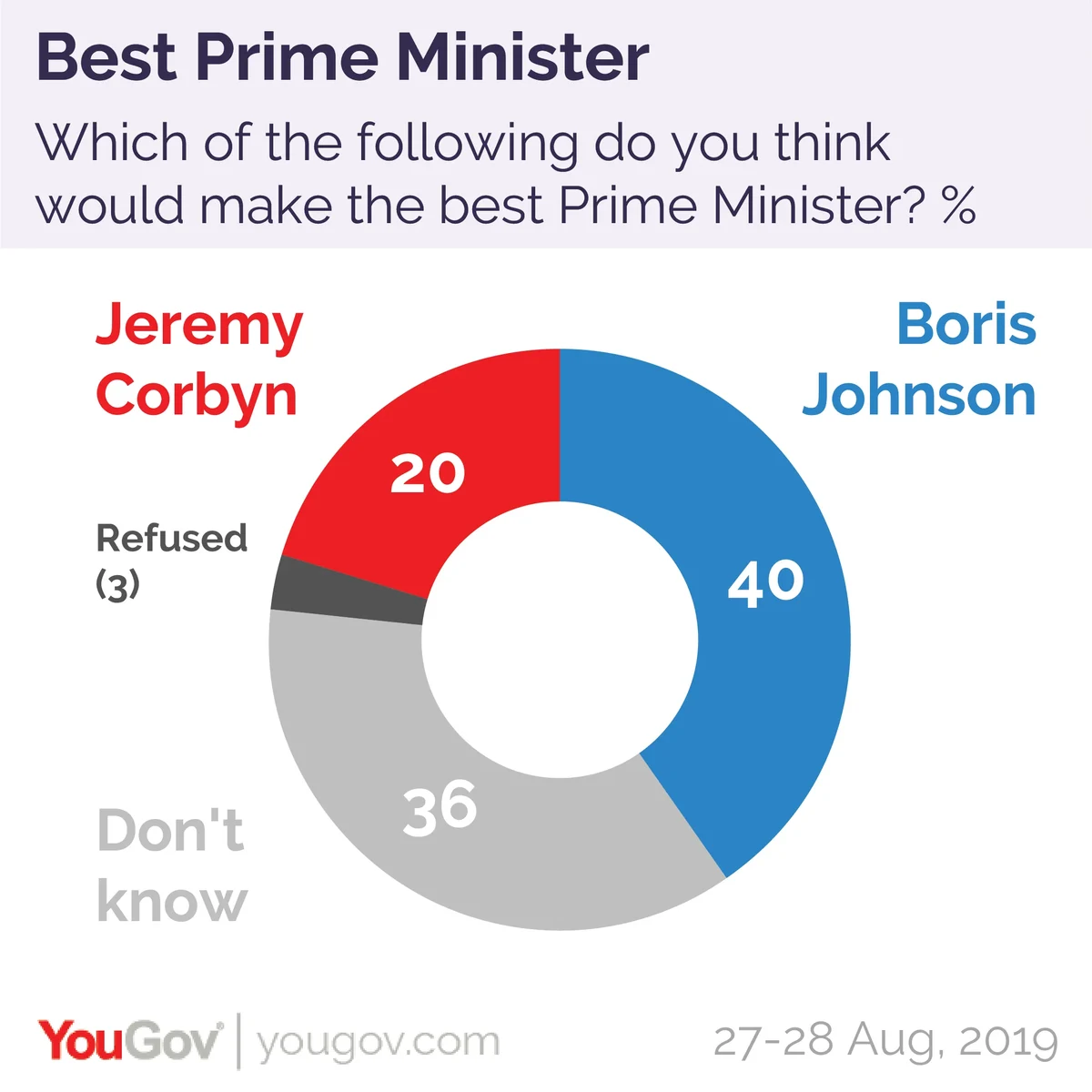

Added to this, Boris Johnson is beating Jeremy Corbyn by 40% to 20% when it comes to public opinion on who would make the best prime minister. He is now the clear favourite going into a potential autumn election, and these numbers would translate into a very comfortable Conservative majority.

But polling is only ever a snapshot of public opinion at any one point, and given the unpredictability of politics over the past half-decade, it would be naive to see an upcoming election as a done deal. If Johnson’s victory relies on a more united leave vote than remain vote, there are lots of ways it could come undone.

On the leave side, a revival in the fortunes of Nigel Farage’s Brexit partycould divide the vote once more. After topping the polls in the European parliament election, many who voted Conservative at the last election flirted with the idea of also voting for Farage’s new outfit in a general election as well. They peaked at 26% in our general election polling, with nearly half (45%) of 2017 Conservative voters saying they would back the party. Since Johnson became prime minister, however, many of these voters have returned to the Conservative fold, with the Brexit party dropping down to just 13% in our latest poll.

However, with such a large group of voters clearly indicating they were willing to defect from the Conservatives over Brexit, this is clearly a block of voters the new prime minister needs to concern himself with. And if we end up in circumstances where Johnson can be accused of being weak on Brexit (for example if he were forced by parliament to delay Brexit until after 31 October) it is easy to see how these voters might abandon the Conservatives again.

On the remain side, the split vote could start to coalesce around one of the parties fighting to prevent no deal, although there are still obstacles to this happening. On the one hand, given Corbyn’s dire personal ratings, with 70% of the public holding an unfavourable view of him, he will find it tricky to bring more people into the Labour camp. On the other hand, there is still a chunk of loyal Labour voters who wouldn’t be willing to back the Lib Dems, and the party has often been squeezed out of political coverage by our two-party system.

Even if the remain vote does remain divided, and the leave vote united, the remain parties could still try to combat the difficulties of first-past-the-post through electoral pacts. These would work by all bar one of the remain parties standing aside in marginal seats to allow the strongest party in that area a clean run against the Conservatives. The tactic was successfully used in the Brecon and Radnorshire byelection last month, where Plaid Cymru and the Greens stood aside to help the Lib Dems gain the seat.

The Labour party’s reluctance to go along with such a plan will make such pacts far less successful, although even if the parties don’t officially stand candidates down, they could still target their campaigning to more effectively combat the difficulties of first-past-the-post. In addition, we will likely see significant efforts to promote tactical voting by pro-remain forces.

Johnson’s victory is like a three-legged stool – it relies on a united leave vote, a divided remain vote and a first-past-the-post electoral system that rewards the first and punishes the second. A Conservative majority is still the most likely outcome, but if any one leg fails, it can topple.

Image: Getty

This article previously appeared in The Guardian