A guest commentary by Oxford University's Professor Stephen Fisher

Some people think MPs should represent their constituents’ views, while others believe MPs should act in the national interest. A select group, call them party leaders, think they should dictate how MPs vote in parliament.

With MPs due to vote on the government’s Brexit deal next week, YouGov asked, on 5th and 6th December, a representative sample of 1,713 adults in Britain about how MPs should go about deciding whether or not to approve Theresa May’s Brexit deal.

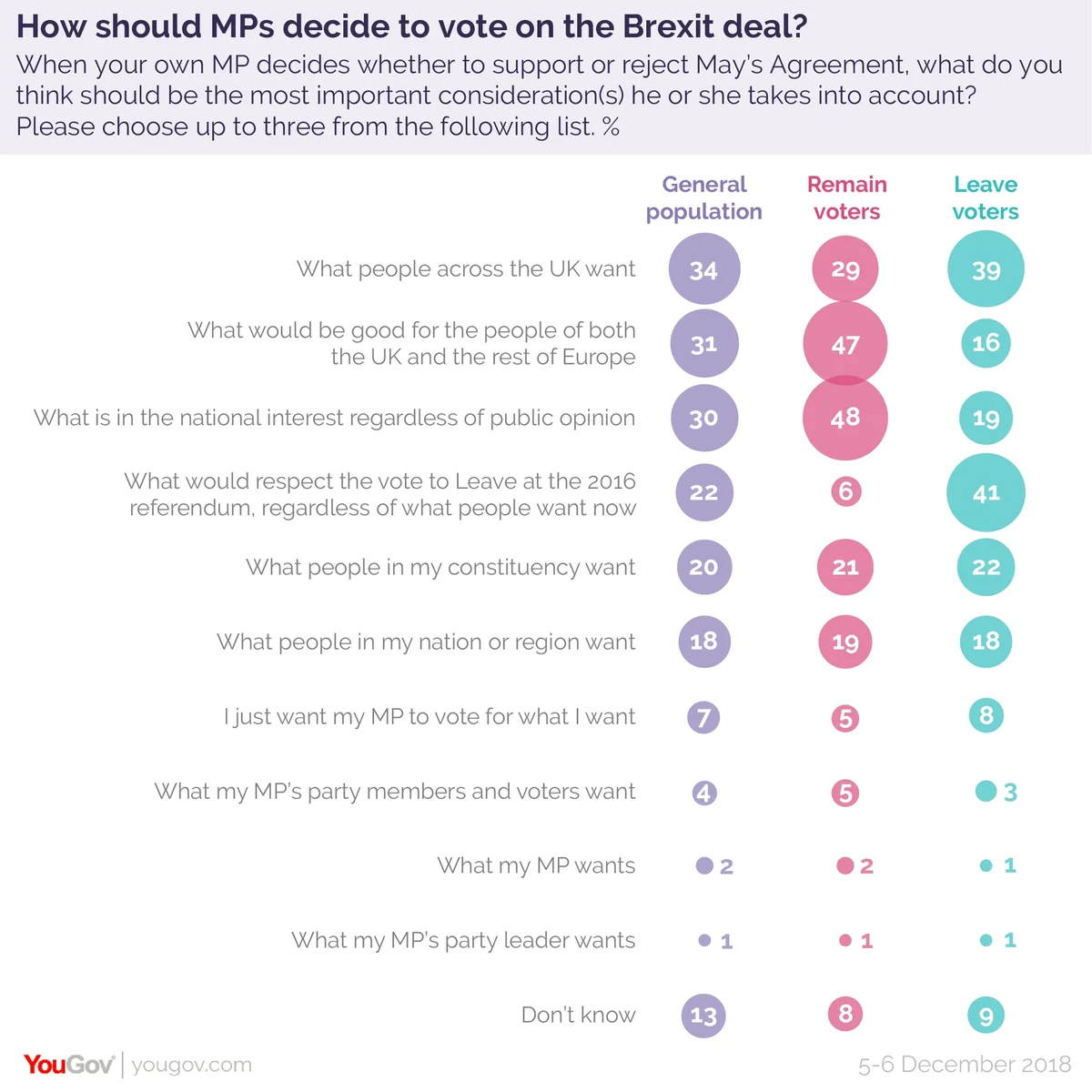

Respondents were asked which of a list of potential considerations were the most important for their MP to take into account. As the following graphic shows, there was no over-riding priority. The most frequently chosen option, “what people across the UK want” was chosen by barely more than a third of respondents.

The UK media has focussed almost entirely on the implications of the deal for the UK alone, largely ignoring the consequences for other EU countries. It is perhaps then surprising that the second most important consideration for MPs, selected by 31%, is “what would be good for the people of both the UK and the rest of Europe.” This option was chosen by as many as 47% of those who voted Remain in 2016, but also 16% of those who voted Leave. Women (37%) were more likely than men (25%) to say that MPs should consider what would be good for the rest of Europe. This gender gap exists among both Leavers and Remainers, and among those who did not vote in 2016.

Some 30% thought MPs should consider “what is in the national interest regardless of public opinion.” The phrase, “national interest” is used by politicians of all stripes to justify whatever they want. Perhaps it was not chosen still more often because it was coupled with the idea of disregarding public opinion. However, people who picked this option, as one of their three possible choices, were almost equally as likely as those that did not to also chose “what people across the UK want.” Thinking that MPs should act in the “national interest” does not preclude wanting them to also take public opinion into account.

The choice between the national interest and public opinion might well have been one that people took in light of their own views on the Brexit. Those voted Leave were more likely to identify “what people across the UK want” as an important consideration than they were to pick the national-interest option (by 39% to 19%). It was the other way round (with corresponding figures of 29% and 48%) for Remain voters. If people are engaging in so-called “motivated reasoning” then these figures suggest that Leavers are more likely to think that their preferences are in line with public opinion, while Remainers are more likely to think that what they want is in the national interest.

More detailed geographical considerations were also relevant. Some 18% (including 27% of Scots) thought that MPs should consider public opinion in their nation or region, while 20% said it was important for MPs to take constituency opinion into account. That these options were chosen less frequently than the UK-public-opinion and UK-and-Europe options suggests that people care about others outside their particular part of the kingdom.

Along with “national interest”, the notion of “respecting the result of the referendum” is commonly used in public debate, particularly by Brexiteer politicians. While the former is clearly more popular among Remainers than Leavers (by 48% to 19%), the latter is the most polarising of the considerations listed. Some 41% of Leave voters said that MPs should consider, “what would respect the vote to Leave at the 2016 referendum, regardless of what people want now.” This was the single most important consideration for Leave voters. By contrast only 6% of Remain voters thought this was an important consideration for MPs.

Strikingly unimportant for the vote on the government’s Brexit deal were considerations of party. Although voters are supposed to be hostile to divided parties, there is practically no sign of demand for party cohesion among MPs. Just 4% said it was important for MPs to take the opinions of their “party members and voters” into account. Still fewer thought MPs should pay attention to their party leader. Attracting just 1% of respondents, that was the single most unimportant consideration, overall and for Remainers as well as Leavers. On this occasion at least, voters want MPs to act independently of their party to represent broader, especially national, considerations.

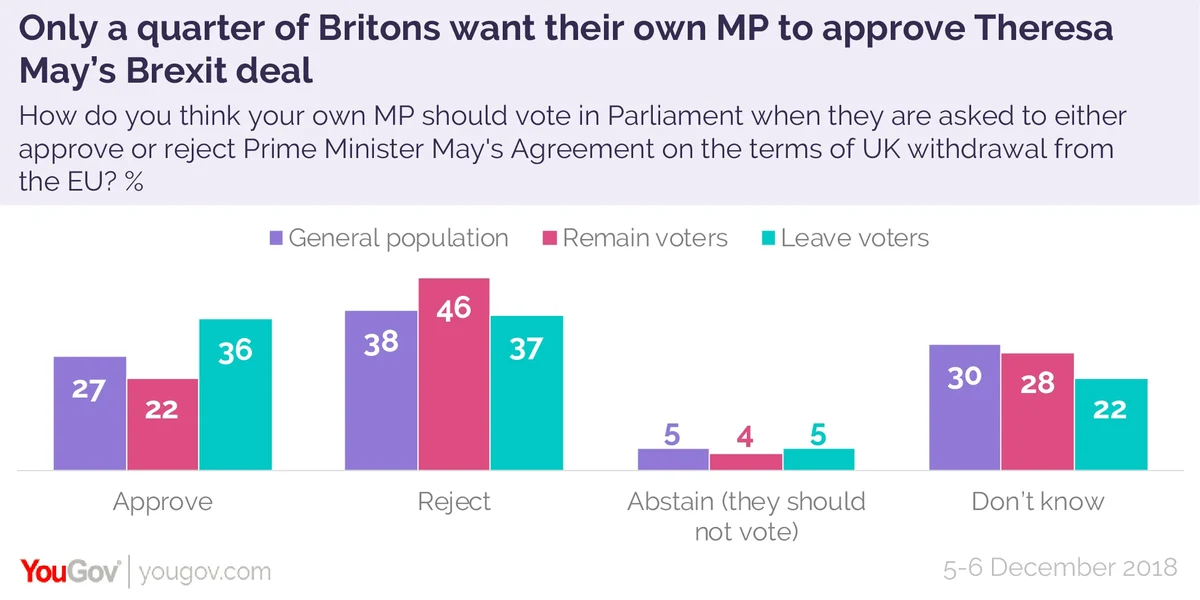

Having been asked what their MP should think about when deciding how to vote, respondents were also asked how they think their MP should vote on the deal in parliament next week. The graphic below shows the distribution of answers. Just under a third, 30%, said “Don’t Know”. This is much higher than the 13% who did not know which of the potential considerations MPs should take into account. This shows that not all the chosen considerations were the result of motivated reasoning. The public are clearer about what they think are the principles that MPs should follow when deciding than they are about which way MPs should vote on the deal.

More people, 38%, think that their own MP should reject the deal than say their MP should approve it (27%). Overall these figures are rather similar to those from a YouGov poll last week asking whether the respondents themselves supported or opposed the deal. Then, 25% expressed support, 44% opposition and 30% said “Don’t Know”. If anything Leavers are now a bit more enthusiastic and Remainers a little more hostile. But overall little has changed, except that there is much less time left before the parliamentary vote.

Photo: Getty