The Lib Dems' attempt to style themselves as "the party of the 48%" was fraught with difficulty, put it may pay off yet

This could have been a triumphant conference for the Liberal Democrats. After the EU referendum it seemed possible that in June’s general election it would capitalise on being “the party of the 48%” and in doing so reverse the disastrous losses it suffered in 2015.

But it wasn’t to be. While it picked up a handful of extra MPs in June, the party actually secured fewer votes than it did last time out. So why wasn’t there a surge in Liberal Democrat support and what must it do for there to be a true #libdemfightback?

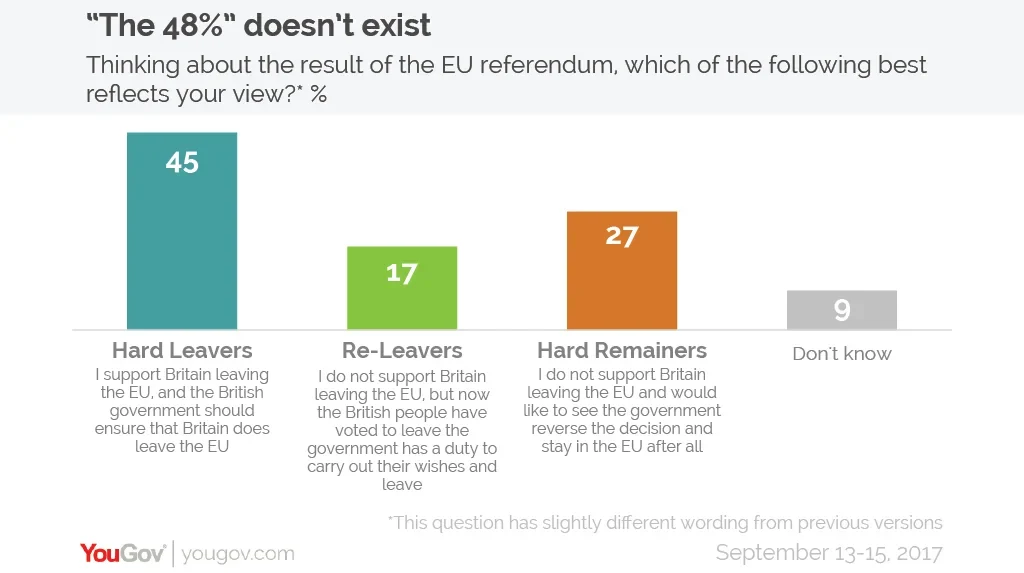

The core problem is that “the 48%” never really existed. Those who voted to stay in the EU last year are clearly split between those “Hard Remainers” (27%) who want the government to overturn the referendum result, and the “Re-Leavers” (19%) who believe that the government has a duty to carry out the electorate’s wishes (the rest said they “didn’t know”).

“Hard Remainers” were hard nuts to crack

In the wake of the referendum, the Lib Dems focused attention on those who wanted to stay part of the European Union. A target group representing of 27% of the electorate represented a decent audience for a party that only received 8% of the vote in the 2015 election. However, the Liberal Democrats have not made deep inroads into the “Hard Remain” vote for two reasons.

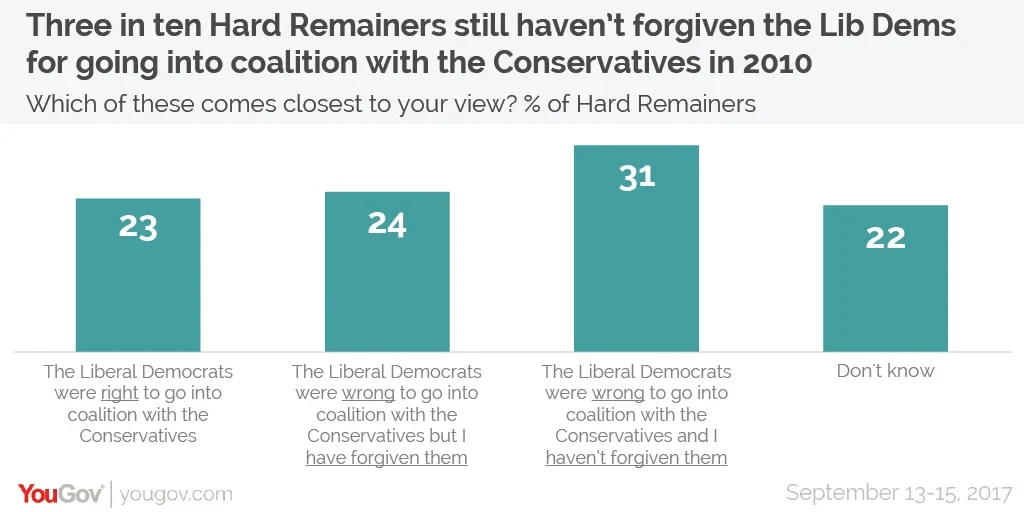

The first reason is the long shadow of the coalition. Overall, the majority (55%) of “Hard Remainers” think that the Lib Dems were wrong to go into government with the Conservatives and three in ten (31%) still haven’t forgiven the party for being part of the coalition. The figure is less surprising given those committed to continued EU membership are more likely to be younger graduates that may still fell particularly angry about the tuition fee increase.

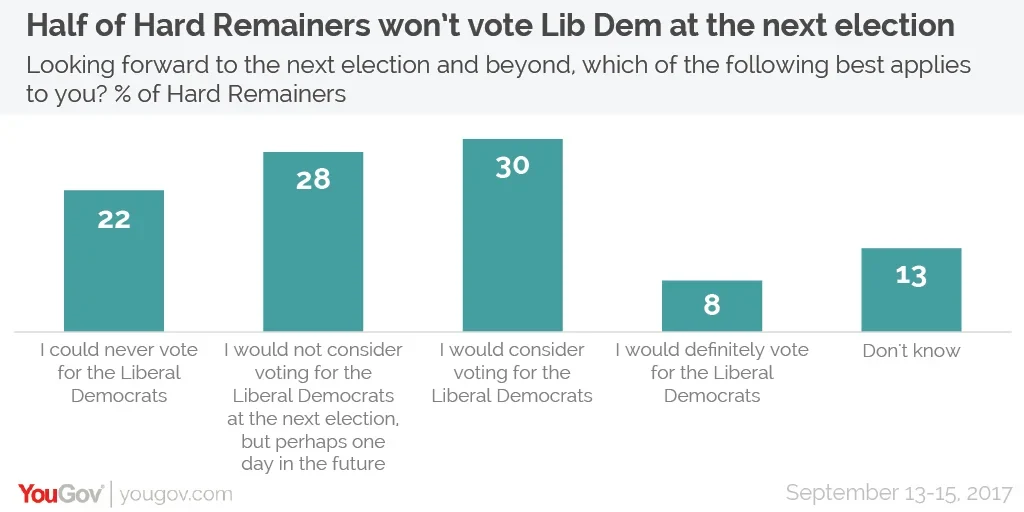

Being in the coalition still hampers support for the party. “Broken promises” were the main reason that 2010 Lib Dem voters that deserted the party in 2015 didn’t return to the fold in 2017. Furthermore, over a fifth (22%) of “Hard-Remainers” say they could never vote for the Liberal Democrats while a further 28% state they wouldn’t consider supporting the party at the next election they might do “one day in the future”.

The second reason the Liberal Democrats have not cut into the “Hard Remainers” is that the group had much stronger ties to Labour than many anticipated. Nearly half (46%) of those committed to continued EU membership supported Labour in 2015 and trying to lure these voters into the Lib Dem column became increasingly difficult after the Corbyn surge towards the end of the campaign.

But as well as failing to snare much of the “Hard Remain” vote, the Lib Dems’ unapologetically pro-EU strategy risked alienating the 29% of the party’s 2015 vote that subsequently voted Leave in the referendum. When combined, all these factors mean there were few constituencies with enough potential Lib Dem voters for the party to win many seats.

Where do the Lib Dems go now?

Given all these problems with the party’s 2017 election strategy, what should Vince Cable do now?

While the old saying states that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results, this may not apply for the Lib Dems. This is because the size of the party’s potential audience could increase as we head towards the next general election – purely due to the passing of time.

It will only become harder for people to keep holding the coalition against the party and it may become easier for them to forgive and forget instead. This could be further helped by the fact that just 12% of “Hard Remainers” believe the party would enter into coalition with the Conservatives again (compared to 25% who think they would go into coalition with Labour).

The 2017 election happened early in the Brexit negotiation process and should things turn sour economically as a result of the UK leaving the EU it may increase the number of those with misgivings about the referendum result. If this were to happen it might benefit the Lib Dems who may be rewarded for being seen to have been on the right side of the debate from the start.

It would be wrong to write the Lib Dems off just because their fightback didn’t materialise in 2017. It may just be that they had the right campaign strategy at the wrong time. However, it may be that, with a resurgent Labour party picking up swathes of anti-establishment votes, Vince Cable’s party continues to attract single-digit support.

Photo: Getty