As part of the YouGov-Cambridge Programme, Dr Finbarr Livesey made a written submission to the House of Commons Speaker’s Digital Democracy Commission, investigating British attitudes to representation and how the public want to engage in decision making in Parliament. Full analysis and discussion is being prepared as a set of journal articles and will be available in 2015.

(Reposted from the Speaker’s Digital Democracy Commission here)

(See the main portal for the Democracy Commission here)

Through the life of the current UK Parliament, there have been growing calls for greater public engagement in policy making, exemplified by the Public Administration Select Committee’s report titled Public Engagement in Policy-Making. The Coalition government which came to power in 2010 enshrined their position on public engagement in the Plan for Civil Service Reform which stated that “Open policy-making will become the default”. It appears that there is a large desire to open up the policy-making process to both improve the outcomes of the process and to disperse power away from Westminster and to the individual.

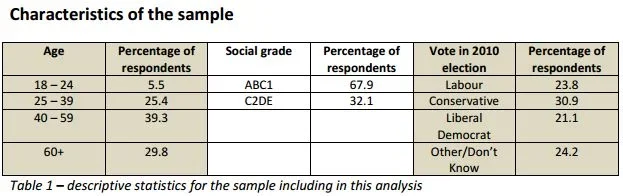

In an attempt to understand public opinion towards issues of representation and engagement for the British public, a survey was designed and completed in partnership with YouGov in August of 2014.1 The survey asked a series of questions which looked at what the public feel is important when MPs are making decisions, their current and desired levels of involvement in decision making in Parliament, and the channels or activities that they say they would use to engage.

The following sections provide an overview of the initial findings, as this research work is ongoing and the completed analysis is being prepared for submission to academic journals in 2015.

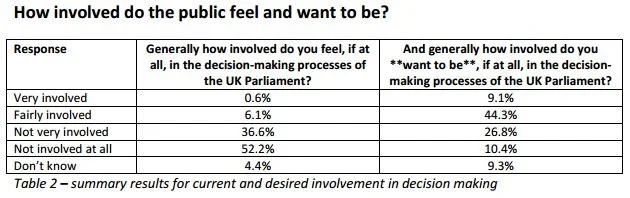

The obvious comparison for these linked questions is that while just under 7% of the sample feel that they have some involvement in decisions made in Parliament, over 53% would like to be involved in some form. This is a significant gap of 46% between the current perceived involvement and the desired involvement of the public across Great Britain.

There are gender and party affiliation differences in these responses. These include:

- More women (56%) than men (44%) indicating that they want to be involved in decision making in Parliament

- Fewer Liberal Democrat voters (4%) saying they feel involved than Labour (9%) or Conservatives (9%)

- Fewer Conservative voters expressed a desire to be involved (51%) than Liberal Democrats (56%) or Labour (60%)

Should decision making be left to experts?

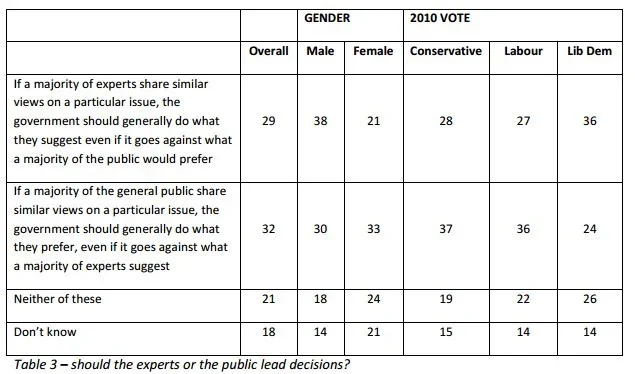

Attempting to get a different perspective on the desire of the public to be involved in decision making, a contrast question was included which asked each respondent to choose from one of two statements when thinking about how the government makes decisions on issues such as housing, healthcare, and education:

- If a majority of experts share similar views on a particular issue, the government should generally do what they suggest even if it goes against what a majority of the public would prefer

- If a majority of the general public share similar views on a particular issue, the government should generally do what they prefer, even if it goes against what a majority of experts suggest

The results are interestingly relatively evenly divided between these options, neither option and those who say they don’t know (Table 3).

The differences for men and women are significant, with almost twice as many men indicating that the experts’ view should be taken above that of the public. Again the responses from those who voted Liberal Democrat in the 2010 election are statistically different from the other parties, as they trust the experts more than other parties (36% for Liberal Democrats compared to 28% for Conservatives and 27% for Labour supporters). It appears that Conservative and Labour supporters trust the public more than experts, where the reverse is true for the Liberal Democrats.

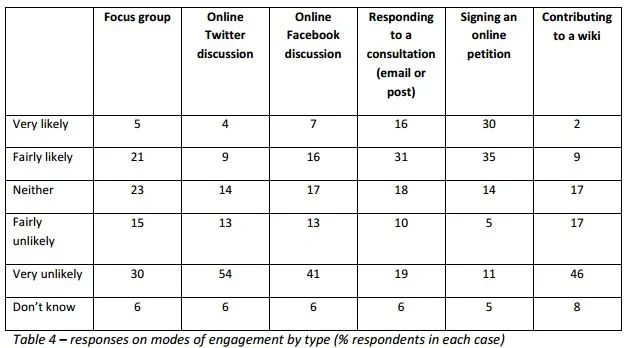

What modes of engagement are most popular?

Whether people are or are not engaged is one aspect of this problem, another is the channels that they are likely to use to be engaged in decision making. A series of questions asked how likely respondents were to use a set of channels in the future for an issue of importance to them. These were:

- Focus groups

- Online Twitter discussions

- Online Facebook discussion

- Respond to a consultation (via email or letter)

- Sign an online petition

- Contribute to a wiki

The high level response shows a wide variety of enthusiasm for these different approaches to engaging, with online petitions ranking first (65% for very likely plus fairly likely) as compared to responding to a consultation (48%), participating in a focus group (26%), taking part in a Facebook discussion (23%), a Twitter discussion (13%) and finally contributing to a wiki (11%). These results are summarised in table 4.

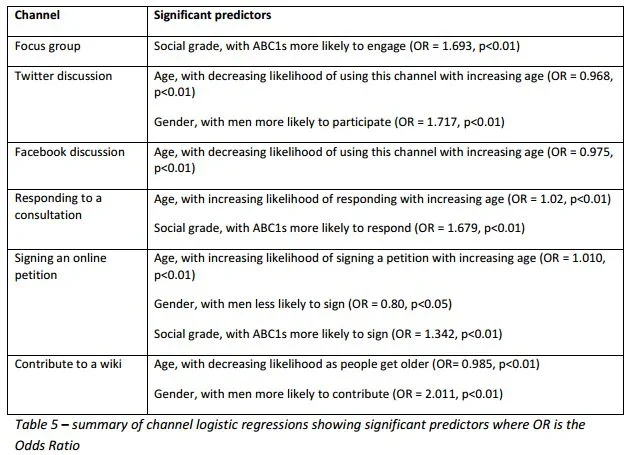

A series of logistic regressions were run for each channel of engagement, using age, gender, party affiliation, region and social grade as predictors and taking very likely and fairly likely to construct a binary outcome variable in each case. Table 5 summarises which predictors were significant in each case, showing the relevant odds-ratio and the significance level. It should be noted that all the models were overall significant but that the pseudo R2 values were low (ranging between 3% and 9%).

While the overall variance explained by these models is low, and so care should be taken not to over emphasise these effects, it appears that across the channels social grade and age matter a lot, and gender has an impact in a number of areas. This would imply that channel selection is going to strongly bias the groups who will engage.

Analysing how the British public expect to be represented by their MPs

Since there is very little work that directly asks the public how they want to be represented this survey also asked how important each of the following should be when MPs are making decisions (respondents rated each on a four point scale from ‘A great deal of impact’ to ‘No impact at all’):

- The MP’s own views

- The majority view of the MP’s constituency

- The majority view at the national level

- The official position of the MP’s party on the issue

These questions allow us to see how strong the response is for the traditional categories of representation (trustee where the representative is expected to make their own decisions versus delegate where the representative is expected to reflect the desire or opinions of their constituents) and to see the influence of party in the opinion of the public.

This question was asked in a generic sense to get a baseline response and then was asked again for a set of different issues (declaring war or taking military action, membership of the European Union, setting or changing tax rates, and setting or changing the retirement age).

The generic response preferences the opinions of the constituency with 74% choosing a great deal of impact or some impact, compared to 62% for the national level and 55% for both the MP’s views and those of the party.

However, comparing the responses for the generic question to those for the specific issues there is a consistent pattern, with respondents deemphasising the MP’s views and that of the constituency in favour of national opinion.

References

1. Fieldwork was conducted online between 10-11 August, 2014, with a total sample of 1,676 British adults. The data have been weighted and results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over. For more information on results please email info@yougov-cambridge.com